Five decades ago, NASA and the U.S. Geological Society launched a satellite to monitor Earth’s landmasses. The Apollo era had given us our first look at Earth from space and inspired scientists to regularly collect images of our planet. The first Landsat — originally known as the Earth Resources Technology Satellite (ERTS) — rocketed into space in 1972. Today we are preparing to launch the ninth satellite in the series.

Each Landsat has improved our view of Earth, while providing a continuous record of how our home has evolved. We decided to examine the legacy of the Landsat program in a four-part series of videos narrated by actor Marc Evan Jackson (who played a Landsat scientist in the movie Kong: Skull Island). The series moves from the birth of the program to preparations for launching Landsat 9 and even into the future of these satellites.

Episode 1: Getting Off the Ground

The soon-to-be-launched Landsat 9 is the intellectual and technical successor to eight generations of Landsat missions. Episode 1 answers the “why?” questions. Why did space exploration between 1962 and 1972 lead to such a mission? Why did the leadership of several U.S. government agencies commit to it? Why did scientists come to see satellites as important to advancing earth science? In this episode, we are introduced to William Pecora and Stewart Udall, two men who propelled the project forward, as well as Virginia Norwood, who breathed life into new technology.

Episode 2: Designing for the Future

The early Landsat satellites carried a sensor that could “see” visible light, plus a little bit of near-infrared light. Newer Landsats, including the coming Landsat 9 mission, have two sensors: the Operational Land Imager (OLI) and the Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS). Together they observe in visible, near-infrared, shortwave-infrared, and thermal infrared wavelengths. By comparing observations of different wavelengths, scientists can identify algal blooms, storm damage, fire burn scars, the health of plants, and more.

Episode 2 takes us inside the spacecraft, showing how Landsat instruments collect carefully calibrated data. We are introduced to Matt Bromley, who studies water usage in the western United States, as well as Phil Dabney and Melody Djam, who have worked on designing and building Landsat 9. Together, they are making sure that Landsat continues to deliver data to help manage Earth’s precious resources.

Episode 3: More Than Just a Pretty Picture

The Landsat legacy includes five decades of observations, one of the longest continuous Earth data records in existence. The length of that record is crucial for studying change over time, from the growth of cities to the extension of irrigation in the desert, from insect damage to forests to plant regrowth after a volcanic eruption. Since 2008, that data has been free to the public. Anyone can download and use Landsat imagery for everything from scientific papers to crop maps to beautiful art.

Episode 3 explores the efforts of USGS to downlink and archive five decades of Landsat data. We introduce Mike O’Brien, who is on the receiving end of daily satellite downloads, as well as Kristi Kline, who works to make Landsat data available to users. Jeff Masek, the Landsat 9 project scientist at NASA, describes how free access to data has revolutionized what we are learning about our home planet.

Episode 4: Plays Well With Others

For the past 50 years, Landsat satellites have shown us Earth in unprecedented ways, but they haven’t operated in isolation. Landsat works in conjunction with other satellites from NASA, NOAA, and the European Space Agency, as well as private companies. It takes a combination of datasets to get a full picture of what’s happening on the surface of Earth.

In Episode 4, we are introduced to Danielle Rappaport, who combines audio recordings with Landsat data to measure biodiversity in rainforests. Jeff Masek also describes using Landsat and other data to understand depleted groundwater.

Learn more about the Landsat science team at NASA.

Learn more about the Landsat program at USGS.

View images in our Landsat gallery.

Trees connect us scientifically, environmentally, and culturally. We all know that trees are vital to our planet’s health. As trees grow, they absorb carbon from the atmosphere, playing a vital role in Earth’s global carbon cycle and helping to regulate Earth’s carbon budget.

But before you read any further, look around…especially if you are outside. Most of you can look in any direction and see a tree. You might wonder about a few things like: “What type of tree is that?” or “Why is that tree so tall or short?” or “How old is that tree?” or even “Was that tree planted by someone, or did the wind blow a seed to where the tree is now standing?”

Or what if you don’t see any trees? What does that signify about the environment? Did nature make it that way, or did humans? All of these are great questions that can help us understand and connect with the environment.

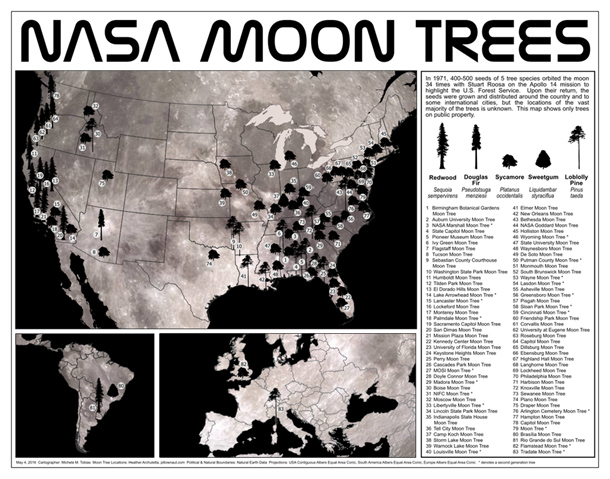

A few trees on Earth also connect us to the Moon. Have you ever heard of “Moon Trees?”

“Moon Trees” never actually grew on the Moon, but their seeds were taken into lunar orbit 50 years ago this week. The NASA Moon Trees history website explains:

Apollo 14 launched in the late afternoon of January 31, 1971, on what was to be our third trip to the lunar surface. Five days later, Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell walked on the Moon while Stuart Roosa, a former U.S. Forest Service smoke jumper, orbited above in the command module. Packed in small containers in Roosa’s personal kit were hundreds of tree seeds, part of a joint NASA/USFS project. Upon return to Earth, the seeds were germinated by the Forest Service. Known as the “Moon Trees,” the resulting seedlings were planted throughout the United States (often as part of the nation’s bicentennial in 1976) and the world. They stand as a tribute to astronaut Roosa and the Apollo program.

Among the Moon Trees that were eventually planted around the United States and the world were sycamores, Loblolly pines, redwoods, sweetgums, and Douglas firs. Though it is unlikely the Moon Tree seeds were changed much by their brief lunar orbit, it is still a wonder that they made it into space and back, and that many of the trees are growing and thriving today.

So, where can you find them? The NASA Moon Trees site has a list, and there is also an article and photographs from our friends at National Geographic. UC Davis data scientist Michele M. Tobias created the map below. You can also learn more about the trees from our colleagues at Marshall Space Flight Center.

Perhaps you might see some Moon Trees in person in the next year or two. If you do, consider making tree height observations using the tree tools on the NASA GLOBE Observer app. When completing your observation, let us know in the app.

Have you ever visited and seen a Moon Tree? Tell us about it below.

When NASA launched the Nimbus-4 satellite 50 years ago, nobody knew the ozone layer over Antarctica was thinning. And nobody knew that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)—long-lived chemicals that had been used in refrigerators and aerosol sprays since the 1930s—were responsible.

But the mission included a sensor called the Backscatter Ultraviolet (BUV) experiment capable of measuring ozone nonetheless. “We simply wanted to measure the atmosphere. It was curiosity-driven research,” said Pawan Bhartia, an atmospheric scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in an interview about the discovery of the ozone hole.

Developed by a team led by NASA’s Donald Heath, BUV was the first space-based instrument to measure the total amount of ozone in the Earth’s atmosphere. “Don was really sweating the Nimbus-4 launch because his MUSE instrument on one of the previous Nimbus satellites ended up in the Pacific Ocean offshore from Vandenberg Air Force Base,” said Arlin Krueger, technical officer for the BUV science team. “That instrument was recovered from the ocean floor and sat on his filing cabinet for years as a reminder that risks are big part of the NASA experimenter’s life.”

Fortunately, the launch went smoothly. The BUV performed well and demonstrated a new way to measure total column ozone. This led to the Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS) on Nimbus-7. The ozone data it collected gave researchers baseline measurements that, in the mid-1980s, helped them recognize that a troubling hole in the ozone layer had opened up.

The global recognition of the destructive potential of CFCs soon led to the 1987 Montreal Protocol, a treaty phasing out the production of ozone-depleting chemicals. Since then, scientists have begun to see definitive proof of ozone recovery.

You can find the latest data and imagery of the status of the ozone hole on NASA’s Ozone Watch website. You can read more about the role that satellites played in the discovery of stratospheric ozone depletion here.

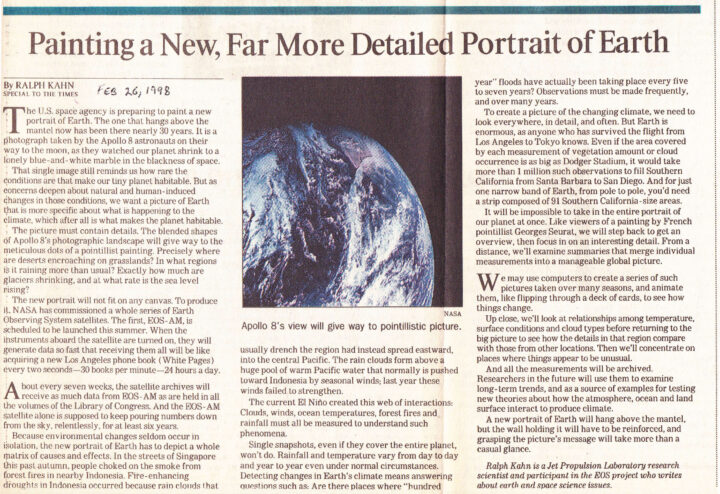

More than 20 years ago, NASA scientist Ralph Kahn authored a column for the Los Angeles Times anticipating the launch of a new satellite — and ultimately a whole fleet of satellites — that would study Earth.

“We want a picture of Earth that is more specific about what is happening to the climate, which after all is what makes the planet habitable,” he wrote. And that picture needed to be rich with detail. “Precisely where are deserts encroaching on grasslands? In what regions is it raining more than usual? Exactly how much are glaciers shrinking, and at what rate is the sea level rising?” he asked.

The first satellite, Terra (originally named EOS-AM), roared into space on December 18, 1999, began collecting data in February and March 2000, and collected its first complete day of MODIS data on April 19, 2000.

“About every seven weeks, the satellite archives will receive as much data from EOS-AM as are held in all the volumes of the Library of Congress. And the EOS-AM satellite alone is supposed to keep pouring numbers down from the sky, relentlessly, for at least six years,” Kahn wrote.

Amazingly, all those numbers from Terra continue to pour down 20 years later. Over time, the flood of data from Terra and several other satellites has turned into scientific discoveries. Bit by bit, the questions Kahn initially posed in his column have been answered.

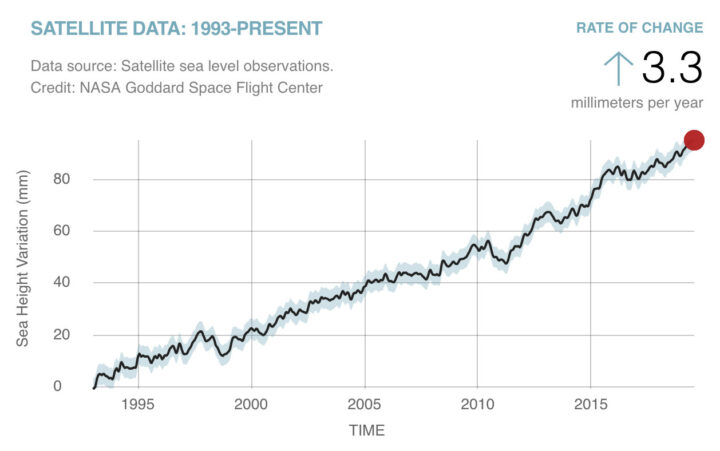

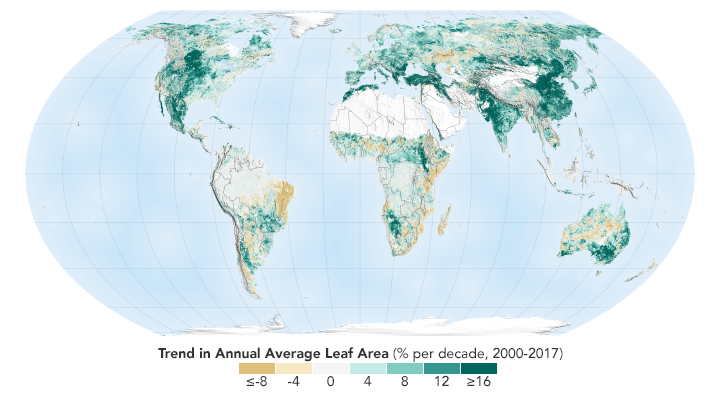

We can say now that sea level is rising at 3.3 millimeters (.13 inches) per year. We can show you a map of where exactly green vegetation has become more common and where it has faded. We can point you to a long-term dataset that will show you precisely where rain has fallen over the past two decades. And we can give you a tour of the world’s glaciers that shows you where they are and many examples of where they are shrinking.

The question to grapple with now: what do we with all this information?

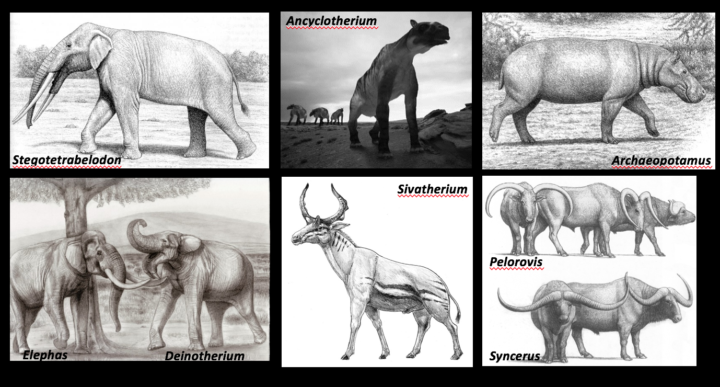

Seven million years ago, some truly spectacular creatures roamed the woodlands of East Africa. There was a moose-like giraffe called Shiva’s beast. There were giant buffalo with horns wider than the animals were tall. And the lumbering creatures known as anthracotheres defy easy categorization.

“Whenever I ask colleagues who study anthracotheres how they describe them, they always say: hippo-pig,” laughed Tyler Faith, curator of archaeology at the Natural History Museum of Utah. As for the buffalo: “This was a horn span of 3 meters (10 feet). I mean this was an awesome buffalo.”

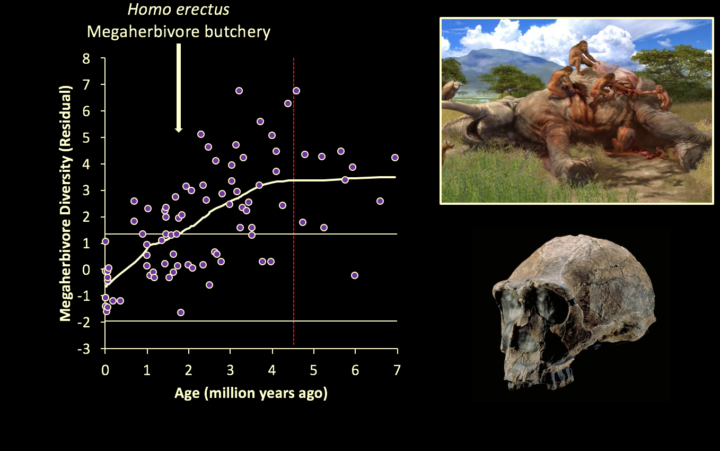

These and several dozen variations of more recognizable African megaherbivores — elephants, rhinos, hippos, and giraffes — all went extinct within the past several million years. For decades, archaeologists have pinned the blame on early humans, particularly Homo erectus, a species that emerged 2 million years ago, walked upright, and had a body plan similar to modern humans. Since Homo erectus made stone weapons and was capable of butchering large game, many archaeologists assumed that it hunted Africa’s megaherbivores into extinction — much like the fossil record suggests Homo sapiens (modern humans) did to the large mammals of North and South America some 11,000 years ago.

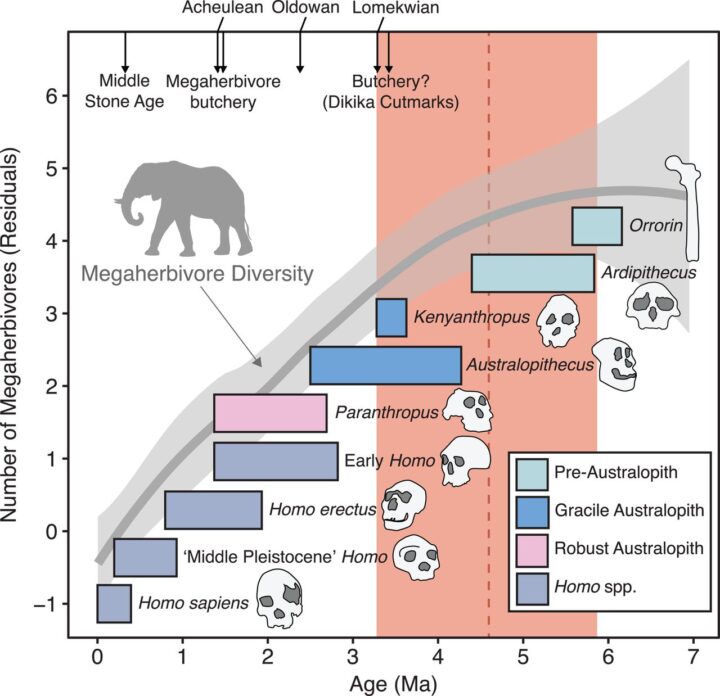

But nobody rigorously tested whether this “overkill hypothesis” fit with the fossil record. “Speculation had been repeated often enough that it just graduated into fact; it became the truth,” Tyler explained during a recent colloquium at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. To check more rigorously, Tyler and colleagues analyzed fossil assemblages from 101 sites in Eastern Africa.

What they found was a surprise. Megaherbivores began disappearing about 4.6 million years ago — long before Homo erectus came on the scene (1.8 million years ago). And there was no increase in the rate of extinctions even when Homo erectus and butchering showed up in fossil records.

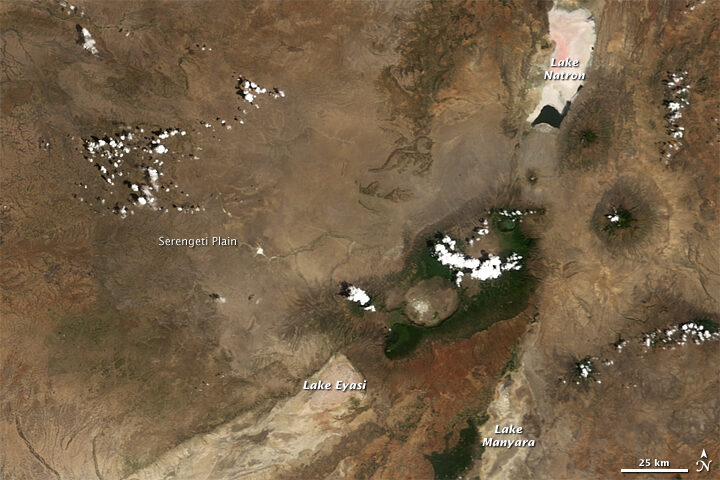

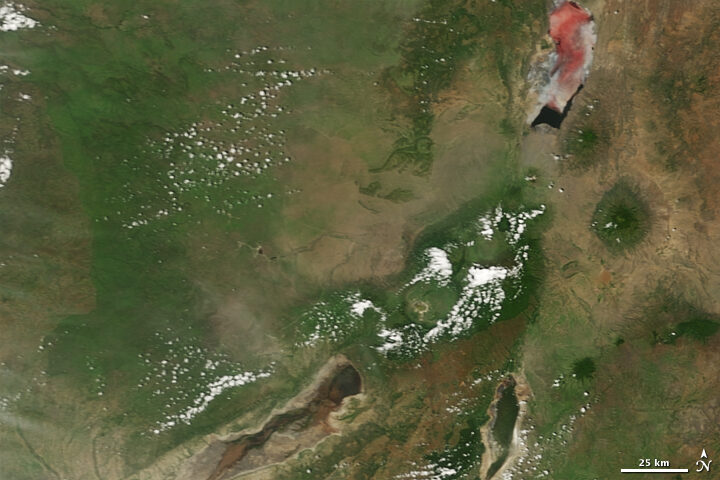

However, when the researchers looked at some key indicators of past environmental conditions, they found one key change — the expansion of grasslands — lined up with the extinctions almost perfectly. Five million years ago, classic open grasslands like today’s Serengeti Plain did not exist in East Africa. Trees and shrubs were a much more dominant part of that African landscape then, explained Tyler.

But as carbon dioxide levels declined, mainly due to orbital variations and changes in the amount of Earth covered by ice, forests retreated and grasslands became dominant. Since many of the megaherbivores fed mainly on woody vegetation, they likely faded away along with their food sources. Meanwhile, other familiar species thrived. The ancestors of wildebeest, hartebeests, Thompson gazelles, oryx, plains zebras, and warthogs — all grazers that live in open habitats — proliferated.

Faith’s bottom line is that it is time to stop blaming Homo erectus for something they didn’t do. “In the search for ancient hominid impacts on ancient African ecosystems, we must focus our attention on the one species known to be capable of causing them – us, Homo sapiens, over the past 300,000 years,” he said.

The March–April 2019 issue marks the thirtieth anniversary of the release of the first issue of The Earth Observer newsletter in March 1989. Alan Ward has spent much of his career working on this publication—including 13 years as Executive Editor—and has written a reflection to mark this milestone. The following version has been edited for length. You can read the full story here.

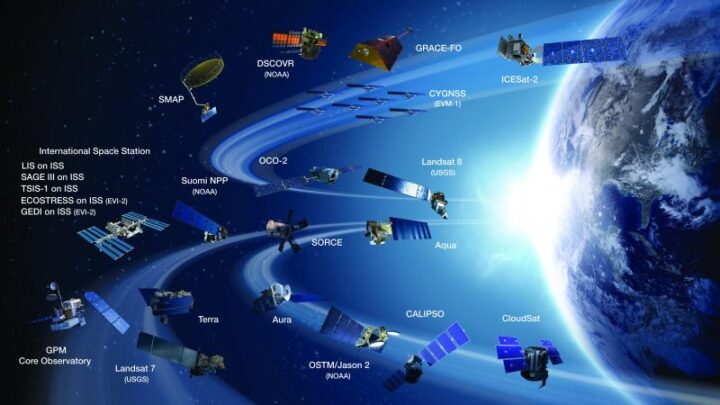

Spurred on by the successes of pioneers in satellite remote sensing, in the early-to-mid-1980s a concept emerged to obtain coordinated Earth observations from space. The earliest designs envisioned having several large platforms in orbit, each carrying many instruments, that could be serviced via the Space Shuttle, akin to how the Hubble Telescope was reserviced. However, that approach eventually morphed into the present fleet of small-to-mid-sized satellites launched on unmanned rockets: e.g., Terra, launched on an Atlas IIAS rocket; Aqua and Aura, both launched on Delta II rockets. The idea was given a name: the Earth Observing System (EOS).

Making EOS a reality would require a fundamental shift in how scientists studying Earth approached their research. Traditionally, individual science disciplines tended to focus on their own areas of expertise, and only occasionally worked together. The idea behind EOS was to study the Earth as a system of interrelated systems—an approach that came to be known as Earth System Science. Functionally, that meant that scientists from different disciplines would need to collaborate much more frequently than they had in the past.

In short, EOS was a grand vision: that we’d someday have a fleet of satellites (along with complementary ground observations and computing systems) continuously taking the pulse of our home planet and sending back large amounts of data—and that scientists would come together to work on related topics. But just how would it all work in practice? No one knew for sure back then. Ask anyone who attended early EOS meetings what they were like and they are likely to use words such as “chaotic” and “challenging” to describe them. In an article he wrote for The Earth Observer, Darrel Williams [former Project Scientist for Landsat 7, currently Chief Scientist at Global Science & Technology, Inc.] recalled that Pier Sellers once described the overall experience of trying to take EOS from idea to reality as being, “…like putting socks on an octopus.”

Sellers definitely had a unique way with words. Whatever creative metaphor one might use to describe it, there is no doubt that those first EOS investigators had huge challenges before them! Not only did they have to work out the details of the flight hardware and computing systems for EOS almost from scratch, but they also had to figure out the practical details of how they would actually work together.

As challenging as developing space flight hardware was (and still is), at that time there was an even larger logistics issue that needed to be addressed. A huge program involving hundreds of researchers strewn all over the nation—and eventually the globe—was trying to get off the ground, and the participants needed the means to communicate. The Internet, which we take for granted today, was in its infancy at that time. If you wanted to get the word out about upcoming meetings, results from those meetings, announcements, and the like, print media was still the way to go. Enter The Earth Observer!

Space does not permit the full story of the intimately interconnected history of the evolution of The Earth Observer and EOS to be repeated here. For this context, it suffices to say that the idea, or concept of EOS faced a difficult journey—and evolved a great deal—before it became what it is today, and that, from its inception, The Earth Observer has chronicled that story.

By the time I made my first contribution to The Earth Observer in 2001, the EOS Earth observing satellite fleet was beginning to take shape. Terra had been launched only a couple years earlier and the other flagship missions (Aqua and Aura) would follow in the next three years. During my tenure, I’ve watched the EOS Program come of age. The Earth Observer has chronicled the establishment and now graceful aging of members of NASA’s Earth-observing fleet of satellites, and has also reported on airborne and ground-based sensors.

We continue to report on NASA Earth Science as we move beyond the EOS era into the Suomi NPP and JPSS era, and into other endeavors such as Decadal Survey missions, including the Earth Venture element. We’ve reported on the launches of new (or recently launched) missions along the way, as well as on the remarkable scientific achievements of existing platforms as, one by one, they exceeded their planned mission lifetimes—often by many years—and celebrated a decade or more in orbit.

I noted earlier that EOS wasn’t simply a satellite-based program. The Earth Observer has also reported on the complementary ground elements, describing results from field campaigns and other ground-based observation programs over the years.The Earth Observer has also published feature articles on more-general topics, such as Earth Science Mission Operations, responsible for keeping the fleet flying safely, and Earth Science Data Operations, which includes the EOS Data and Information System, better known as EOSDIS.

Perhaps the series I take the most personal pride in is our Perspectives on EOS series, which ran from 2008 through 2011. It really didn’t begin with a series in mind; it started with an article that I wrote for the newsletter’s twentieth year, and grew organically into a compendium of recollections and memories from key members of the EOS program. It is often said that history is the telling of a personal story, and that was certainly true with these articles, as the storytellers had actually lived them.

In many ways, the current publication doesn’t look much like the first issue did in March 1989, shortly after the official beginning of EOS. However, while much has changed aesthetically and in terms of content in 30 years, The Earth Observer’s core commitment remains the same as it has always been: to report timely news and events from NASA’s Earth Science Program.

It has been my honor to serve as executive editor for a baker’s dozen of years, and I look forward to seeing what comes next for The Earth Observer as we begin our fourth decade. I think it’s been a good run so far—but I hope our best is yet to come!

On April 29, 1999, NASA Earth Observatory (EO) started delivering science stories and imagery to the public through the Internet. So much has changed in those 20 years…

+ In 1999, about 3 to 5 percent of the world had Internet access. About 41 percent of American adults used the World Wide Web, most often to look at the weather. Today an estimated 56 percent of the world’s population (4.3 billion people) are active on the Internet.

+ At the end of the 20th century, all EO readers came to us through a computer, mostly desktops. One third of them were connecting via dial-up modem. Today, about 40 percent of our audience arrives to the web site via mobile phones and tablets on public wifi and cellular networks. Yet even now, 65,000 of our most loyal followers subscribe to our newsletters. Many others subscribe to our RSS feeds.

+ In 1999, “social” media mostly consisted of chatrooms and newsgroups. Even by 2005, only 5 percent of Americans were using social media. Today about 69 percent of adults use social media, and people are just as likely to see Earth Observatory content on social platforms as on our web site. Ten million people follow EO and NASA Earth science on Facebook, with 1.3 million more on Twitter, and 500,000 on Instagram.

+ When EO launched, images from Earth science satellites were generally available about a month after acquisition. Public access to science data and imagery was extremely limited, highly filtered, and sometimes required a fee. Two decades later, many NASA Earth science observations are available freely on the web within hours of acquisition.

+ On our first day online, the site got 400 pageviews–most of them were likely colleagues and relatives. Today we get about 50,000 views per day.

+ In our first year, we published 35 “Images of the Week” and 9 feature stories. By 2001, we started delivering an Image of the Day. Since launch, we have published more than 6,900 Images of the Day, 8,300 natural hazards images, and 450 features and videos. Yes, more than 15,000 image-driven stories, and all of them are still available in our archive.

+ In 1999, two members of our staff were in elementary school and three were in high school. The readers of EO Kids were not born yet.

The technology of science and the Internet has changed in a generation, and our site has evolved and grown with the changes. But our core values have not changed. You find us on more platforms and with some new approaches, but you can still count on us to deliver beautiful, newsworthy, interesting, and scientifically important images and stories. Our editorial team has more than 110 years of experience in science communication and data visualization, and we bring that depth of knowledge to every story, 365 days a year.

None of this would be possible without the many scientists, engineers, communicators, data hounds, patrons, and friends inside and outside of NASA who review our work, tip us off to stories and images, share their scientific insights, and inspire and challenge us. Thank you.

As we celebrate our 20th year, we are going to share some looks back and some looks ahead. In the next twelve months, look for…

If you have been with us for many (or all) of our 20 years, thank you. We have some of the most engaged, challenging, and thoughtful readers on the planet, and we work hard to live up to your trust and interest. If you are new to the site, bring a friend. We have 15,000 stories about Earth to share, with more being added every day.

Related Links and References

Earth Observatory 10th Anniversary

Pew Research Center (2018) World Wide Web Timeline

Internet World Stats (2019) Internet Growth Statistics

Wikipedia (2019) Global Internet Usage

The shiny metallic orb hanging in the Earth sciences building at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center looks a lot like a fixture you might find at a modern home décor store. But this mid-century marvel is not for sale. It is a restored flight backup of Vanguard II, Earth’s first weather satellite.

The satellite model was hung this week as a reminder of the people who helped build the foundation for making space-based observations of Earth. Paul Newman, chief scientist for Earth science at NASA Goddard, described the satellite:

“Vanguard II was the world’s first meteorological satellite. Developed at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), it was successfully launched by newly formed NASA on February 17, 1959. Vanguard carried two photocells that could scan cloud cover as the satellite rotated in its orbit around the Earth. Unfortunately, the 3rd stage SLV-4 launch vehicle burn caused a precession in the satellite that made the data unusable.”

“While the now silent Vanguard II continues to orbit the Earth, its back-up brother has been restored and mounted in the Goddard Space Flight Center’s Earth Sciences building’s atrium—a fitting resting place amongst the scientists and meteorologists who monitor and study our Earth.”

Some of those scientists, and five retirees from the original NRL Vanguard II team, gathered on April 15, 2019, at NASA Goddard to celebrate the satellite’s 60th anniversary. Angelina Callahan, historian at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, reflected on the historical importance of the Vanguard era. From building satellites and their launching vehicles, to putting satellites in orbit and tracking them, the achievements of the program helped pave the way for satellite missions that followed.

The reflection was also a study on how much has changed. Ron Gelaro, an atmospheric scientist at NASA Goddard, discussed weather prediction in the modern satellite era. Vanguard II carried two photocells and weighed just 21 pounds. The Aqua satellite—launched in 2002 to collect information on Earth’s water systems—carries six instruments and weighs more than 6,000 pounds. Gelero noted, however, that satellites are starting to trend back toward smaller vehicles, such as constellations of microsatellites.

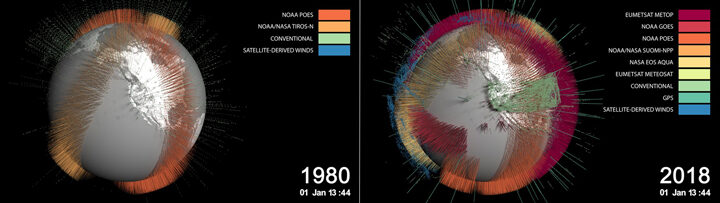

The amount of observations available for understanding weather and climate have also skyrocketed over the decades. For example, MERRA-2 is a reanalysis project at NASA Goddard that combines satellite measurements of temperature, moisture, and winds in the GEOS model. In 1980, MERRA assimilated 175,000 observations for every six-hour period. That number in 2018 neared 5 million observations.

According to NRL: “The scientific experiments flown on the Vanguard satellites increased scientific knowledge of space and opened the way for more sophisticated experiments. Vanguard was the prototype for much of what became the U.S. space program.”

In fact, about 200 scientists and engineers from the Vanguard program moved from NRL to the newly formed NASA in 1958—forming the core of NASA Goddard. You can read more about Vanguard here.

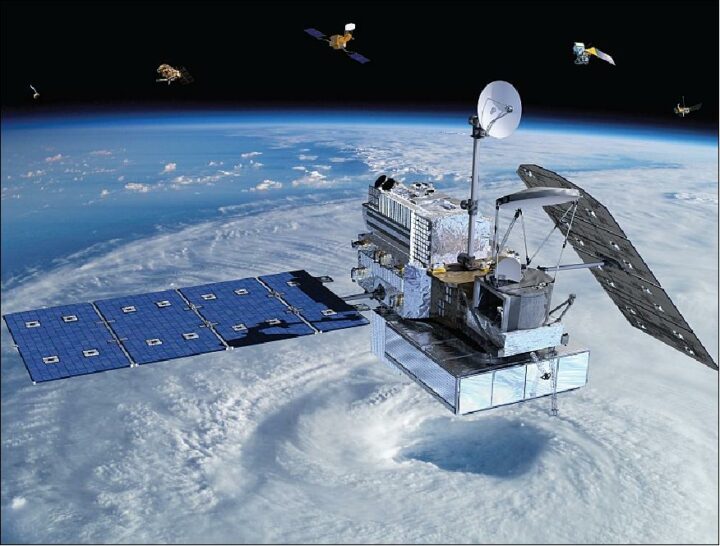

On February 27, 2014, a Japanese rocket launched NASA’s latest satellite to advance how scientists study raindrops from space. The satellite, the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Core Observatory, paints a picture of global precipitation every 30 minutes, with help from its other international satellite partners. It has provided innumerable insights into Earth’s precipitation patterns, severe storms, and into the rain and snow particles within clouds. It has also helped farmers trying to increase crop yields, and aided researchers predicting the spread of fires.

In honor of GPM’s fifth anniversary, we’re highlighting some of our favorite and most unique Earth Observatory stories, as made possible by measurements taken by GPM.

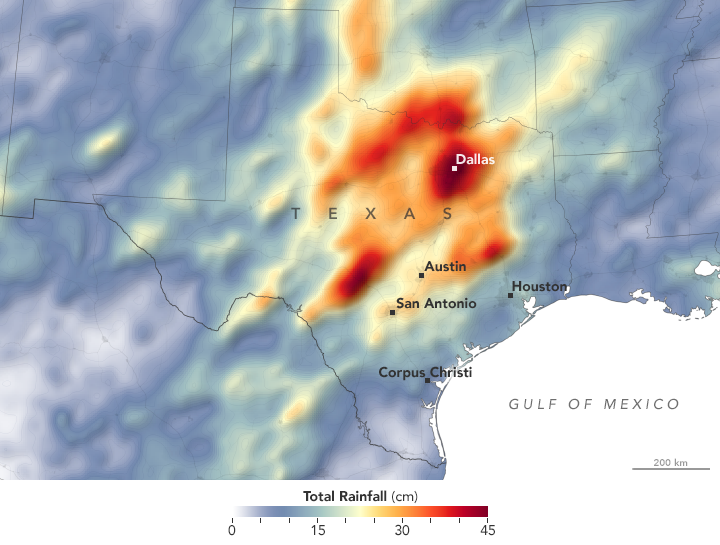

The Second Wettest October in Texas Ever

In Fall 2018, storm after storm rolled through and dumped record rainfall in parts of Texas. When Hurricane Willa hit Texas around October 24, the ground was already soaked. One particularly potent cold front in mid-October dropped more than a foot of rain in areas. By the end of the month, October 2018 was the second wettest month in Texas on record.

GPM measured the total amount of rainfall over the region from October 1 to October 31, 2018. The brightest areas reflect the highest rainfall amounts, with many places receiving 25 to 45 centimeters (10 to 17 inches) or more during this period. The satellite imagery can also be seen from natural-color satellite imagery.

Observing Rivers in the Air

With the GPM mission’s global vantage point, we can more clearly see how weather systems form and connect with one another. In this visualization from October 11-22, 2017, note the long, narrow bands of moisture in the air, known as “atmospheric rivers.” These streams are fairly common in the Pacific Northwest and frequently bring much of the region’s heavy rains and snow in the fall and winter. But this atmospheric river was unusual for its length—extending roughly 8,000 kilometers (5,000 miles) from Japan to Washington. That’s about two to three times the typical length of an atmospheric river.

Since atmospheric rivers often bring strong winds, they can force moisture up and over mountain ranges and drop a lot of precipitation in the process. In this case, more than four inches of rain fell on the western slopes of the Olympic Mountains and the Cascade Range, while areas to the east of the mountains (in the rain shadow) generally saw less than one inch.

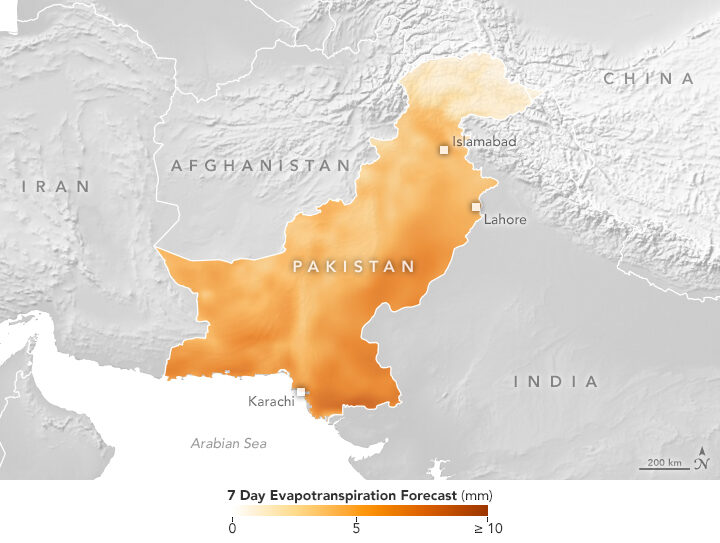

Increasing Crop Yield for Farmers in Pakistan

Knowing how much precipitation is falling or has fallen is useful for people around the world. Farmers, in particular, are interested in knowing precipitation amounts so they can prevent overwatering or underwatering their crops.

The Sustainability, Satellites, Water, and Environment (SASWE) research group at the University of Washington has been working with the Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR) to bring this kind of valuable information directly to the cell phones of farmers. A survey by the PCRWR found that farmers who used the text message alerts reported a 40 percent savings in water. Anecdotally, many farmers say their income has doubled because they got more crops by applying the correct amount of water.

The map above shows the forecast for evapotranspiration for October 16-22, 2018. Evapotranspiration is an indication of the amount of water vapor being removed by sunlight and wind from the soil and from plant leaves. It is calculated from data on temperature, humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation, as well as a global numerical weather model that assimilates NASA satellite data. The team also looks at maps of precipitation, temperature and wind speed to help determine crop conditions. Precipitation data comes from GPM that is combined with ground-based measurements from the Pakistan Meteorological Department.

Forecasting Fire

Precipitation can drastically affect the spread of a fire. For instance, if a region has not received normal precipitation for weeks or months, the vegetation might be drier and more prone to catching fire.

NASA researchers recently created a model that analyzes various weather factors that lead to the formation and spread of fires. The Global Fire Weather Database (GFWED) accounts for local winds, temperatures, and humidity, while also being the first fire prediction model to include satellite–based precipitation measurements.

The animation above shows GFWED’s calculated fire danger around the world from 2015 to 2017. The model compiles and analyzes various data sets and produces a rating that indicates how likely and intense fire might become in a particular area. It is the same type of rating that many firefighting agencies use in their day–to–day operations. Historical data are available to understand the weather conditions under which fires have occurred in the past, and near–real–time data are available to gauge current fire danger.

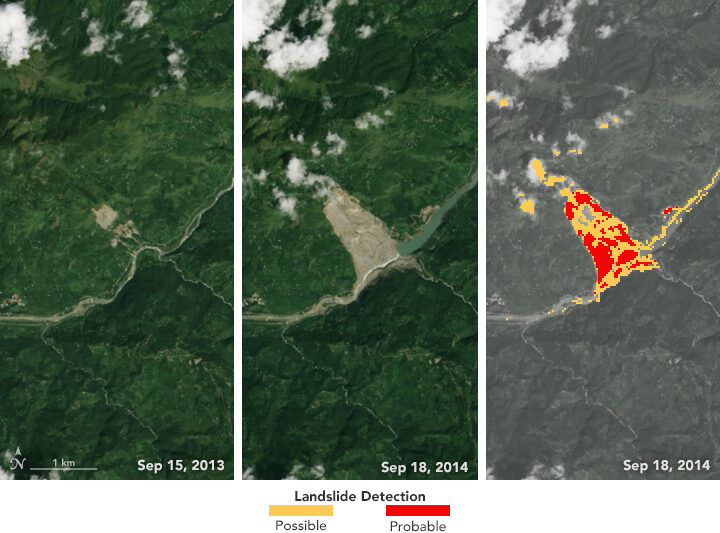

Automatically Detecting Landslides

In this mountainous country of Nepal, 60 to 80 percent of the annual precipitation falls during the monsoon (roughly June to August). That’s also when roughly 90 percent of Nepal’s landslide fatalities occur. NASA researchers have designed an automated system to identify potential landslides that might otherwise go undetected and unreported. This information could significantly improve landslide inventories, leading to better risk management.

The computer program works by scanning satellite imagery for signs that a landslide may have occurred recently, looking at topographical features such as hill slopes.

The left and middle images above were acquired by the Landsat 8 satellite on September 15, 2013, and September 18, 2014—before and after the Jure landslide in Nepal on August 2, 2014. The image on the right shows that 2014 Landsat image processed with computer program. The red areas show most of the traits of a landslide, while yellow areas exhibit a few of the proxy traits.

The program also uses data from GPM to help pin when each landslide occurred. The GPM core satellite measures rain and snow several times daily, allowing researchers to create maps of rain accumulation over 24-, 48-, and 72-hour periods for given areas of interest—a product they call Detecting Real-time Increased Precipitation, or DRIP. When a certain amount of rain has fallen in a region, an email can be sent to emergency responders and other interested parties.

The GPM Core Observatory is a joint satellite project by NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. The satellite is part of the larger GPM mission, which consists of about a dozen international satellite partners to provide global observations of rain and snow.

To learn more about GPM’s accomplishments over the past five years, visit: https://pmm.nasa.gov/resources/featured-articles-archive

To learn more about the GPM mission, visit: https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/GPM/main/index.html

On February 12, 1809, Charles Robert Darwin was born in England in the town of Shrewsbury. The famed naturalist, geologist, and biologist is best known for his 19th century expedition to the Galápagos Islands, which inspired revolutionary insights about evolution and natural selection. Lesser known is that the expedition to the Galápagos was just one part of a much longer journey. The Second Voyage of the HMS Beagle brought Darwin and his fellow travelers to South America, Australia, Africa, and several islands in between. Here are a few interesting places where the HMS Beagle stopped that we have covered in earlier stories.

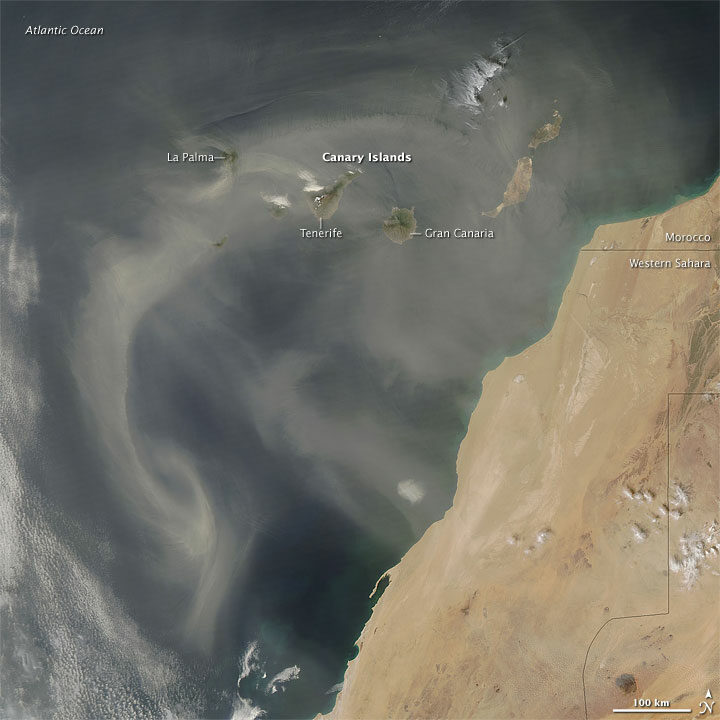

The crew of the Beagle was denied landing on Tenerife because of fears they might be carrying cholera. The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 acquired this image of the island on January 25, 2016.

Darwin was struck by the intensity of the dust in this area. “The atmosphere is generally very hazy, chiefly due to an impalpable dust, which is constantly falling, even on vessels far out at sea,” he wrote. “It is produced, as I believe, from the wear and tear of volcanic rocks, and must come from the coast of Africa.”

Southwest of Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America, the ocean floor rises sharply. Along with the potent westerly winds that swirl around the Furious Fifties, this pushes up massive waves with frightening regularity. Add in frigid water temperatures, rocky coastal shoals, and stray icebergs—which drift north from Antarctica across the Drake Passage—and it is easy to see why the area is known as a graveyard for ships. In his journal, Darwin described the harrowing journey as the explorers tried to round the Horn just before Christmas.

“Great black clouds were rolling across the heavens, and squalls of rain, with hail, swept by us with such extreme violence, that the Captain determined to run into Wigwam Cove. This is a snug little harbor, not far from Cape Horn; and here, at Christmas-eve, we anchored in smooth water. The only thing which reminded us of the gale outside, was every now and then a puff from the mountains, which made the ship surge at her anchors.”

Charles Darwin

The Galapagos archipelago includes more than 125 islands, islets, and rocks populated by a diversity of wildlife. Charles Darwin’s book, The Voyage of the Beagle, cast a spotlight on the Galapagos, which he called “a little world within itself, or rather a satellite attached to America, whence it has derived a few stray colonists.” It was this little world that would revolutionize scientific understanding of biology and lead to Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, which would come to be known as the foundation of evolution.

On this stopover, Darwin had a chance to explore coral reef.

“We paddled for some time about the reef admiring the pretty branching Corals,” he wrote. “It is my opinion, that besides the avowed ignorance concerning the tiny architects of each individual species, little is yet known, in spite of the much which has been written, of the structure and origin of the Coral Islands and reefs.”

The Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus on the Landsat 7 satellite captured this natural-color image of Tahiti on July 11, 2001. This island is part of a volcanic chain formed by the northwestward movement of the Pacific Plate over a fixed hotspot.

All the sea travel offered plenty of time to observe and ponder the intricacies of phytoplankton.

“My attention was called to a reddish-brown appearance in the sea. The whole surface of the water, as it appeared under a weak lens, seemed as if covered by chopped bits of hay, with their ends jagged,” he wrote. “These are minute cylindrical, in bundles or rafts of from twenty to sixty in each…Their numbers must be infinite: the ship passed through several bands of them, one of which was about ten yards wide, and, judging from the mud-like color of the water, at least two and a half miles.”

On August 9, 2011, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on the Aqua satellite captured this image of a similar band of brown between the Great Barrier Reef and the Queensland shore. Though it’s impossible to identify the species from satellite imagery, such red-brown streamers are usually trichodesmium. Sailors have long called these brown streamers “sea sawdust.”