Happy Solstice Day!

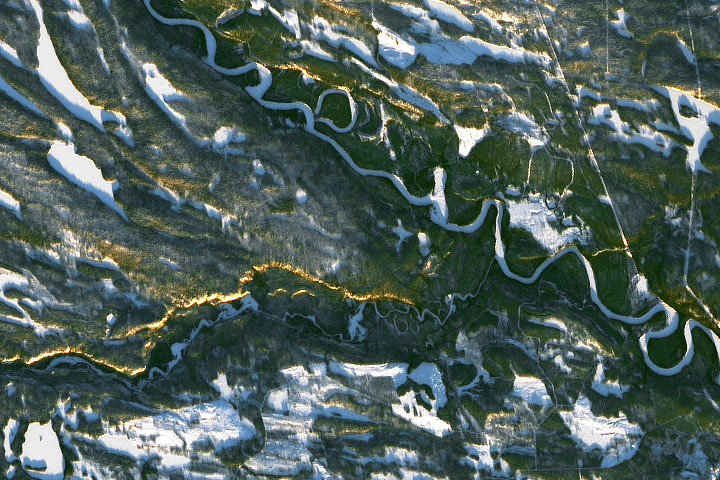

Every month on Earth Matters, we offer a puzzling satellite image. The December 2021 puzzler is shown above. Your challenge is to use the comments section to tell us where it is, what we are looking at, and why it is interesting. In particular this month, what is the golden line/streak across the image?

How to answer. You can use a few words or several paragraphs. You might simply tell us the location, or you can dig deeper and offer details about what satellite and instrument produced the image, what spectral bands were used to create it, or what is compelling about some obscure feature. If you think something is interesting or noteworthy, tell us about it.

The prize. We cannot offer prize money or a trip on the International Space Station, but we can promise you credit and glory. Well, maybe just credit. Within one week after a puzzler image appears on this blog, we will post an annotated and captioned version as our Image of the Day. After we post the answer, we will acknowledge the first person to correctly identify the image at the bottom of this blog post. We also may recognize readers who offer the most interesting tidbits of information. Please include your preferred name or alias with your comment. If you work for or attend an institution that you would like to recognize, please mention that as well.

Recent winners. If you’ve won the puzzler in the past few months, or if you work in geospatial imaging, please hold your answer for at least a day to give less experienced readers a chance.

Releasing Comments. Savvy readers have solved some puzzlers after a few minutes. To give more people a chance, we may wait 24 to 48 hours before posting comments. Good luck!

Update: The answer is the Sápmi region of Finland (formerly known as Lapland), not far from Oulanka National Park. You can read more here. Tom Franco correctly noted the low Sun angle (but it is not a sunset), while Frank correctly noted the proximity to the Arctic Circle.

Every month on Earth Matters, we offer a puzzling satellite image. The February 2021 puzzler is above. Your challenge is to use the comments section to tell us what we are looking at, where it is, and why it is interesting.

How to answer. You can use a few words or several paragraphs. You might simply tell us the location, or you can dig deeper and explain what satellite and instrument produced the image, what spectral bands were used to create it, or what is compelling about some obscure feature. If you think something is interesting or noteworthy, tell us about it.

The prize. We cannot offer prize money or a trip to Mars, but we can promise you credit and glory. Well, maybe just credit. A few days after a puzzler image appears on this blog, we will post an annotated and captioned version as our Image of the Day. After we post the answer, we will acknowledge the first person to correctly identify the image at the bottom of this blog post. We also may recognize readers who offer the most interesting tidbits of information about the geological, meteorological, or human processes that have shaped the landscape. Please include your preferred name or alias with your comment. If you work for or attend an institution that you would like to recognize, please mention that as well.

Recent winners. If you’ve won the puzzler in the past few months, or if you work in geospatial imaging, please hold your answer for at least a day to give less experienced readers a chance.

Releasing Comments. Savvy readers have solved some puzzlers after a few minutes. To give more people a chance, we may wait 24 to 48 hours before posting comments. Good luck!

Trees connect us scientifically, environmentally, and culturally. We all know that trees are vital to our planet’s health. As trees grow, they absorb carbon from the atmosphere, playing a vital role in Earth’s global carbon cycle and helping to regulate Earth’s carbon budget.

But before you read any further, look around…especially if you are outside. Most of you can look in any direction and see a tree. You might wonder about a few things like: “What type of tree is that?” or “Why is that tree so tall or short?” or “How old is that tree?” or even “Was that tree planted by someone, or did the wind blow a seed to where the tree is now standing?”

Or what if you don’t see any trees? What does that signify about the environment? Did nature make it that way, or did humans? All of these are great questions that can help us understand and connect with the environment.

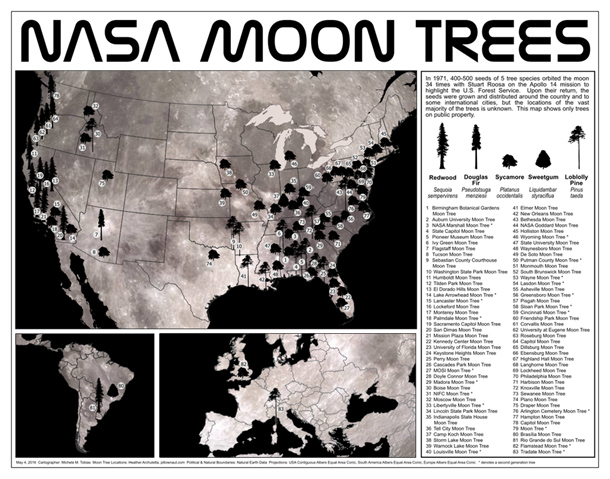

A few trees on Earth also connect us to the Moon. Have you ever heard of “Moon Trees?”

“Moon Trees” never actually grew on the Moon, but their seeds were taken into lunar orbit 50 years ago this week. The NASA Moon Trees history website explains:

Apollo 14 launched in the late afternoon of January 31, 1971, on what was to be our third trip to the lunar surface. Five days later, Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell walked on the Moon while Stuart Roosa, a former U.S. Forest Service smoke jumper, orbited above in the command module. Packed in small containers in Roosa’s personal kit were hundreds of tree seeds, part of a joint NASA/USFS project. Upon return to Earth, the seeds were germinated by the Forest Service. Known as the “Moon Trees,” the resulting seedlings were planted throughout the United States (often as part of the nation’s bicentennial in 1976) and the world. They stand as a tribute to astronaut Roosa and the Apollo program.

Among the Moon Trees that were eventually planted around the United States and the world were sycamores, Loblolly pines, redwoods, sweetgums, and Douglas firs. Though it is unlikely the Moon Tree seeds were changed much by their brief lunar orbit, it is still a wonder that they made it into space and back, and that many of the trees are growing and thriving today.

So, where can you find them? The NASA Moon Trees site has a list, and there is also an article and photographs from our friends at National Geographic. UC Davis data scientist Michele M. Tobias created the map below. You can also learn more about the trees from our colleagues at Marshall Space Flight Center.

Perhaps you might see some Moon Trees in person in the next year or two. If you do, consider making tree height observations using the tree tools on the NASA GLOBE Observer app. When completing your observation, let us know in the app.

Have you ever visited and seen a Moon Tree? Tell us about it below.

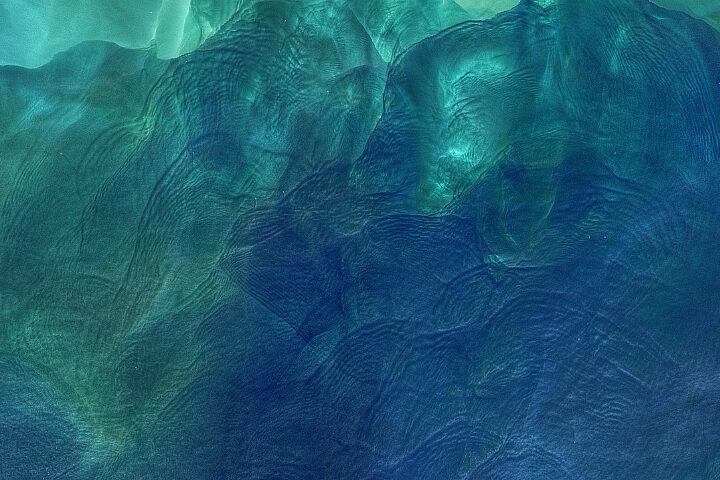

Every month on Earth Matters, we offer a puzzling satellite image. The November 2020 puzzler is above. Your challenge is to use the comments section to tell us what we are looking at, where it is, and why it is interesting.

How to answer. You can use a few words or several paragraphs. You might simply tell us the location, or you can dig deeper and explain what satellite and instrument produced the image, what spectral bands were used to create it, or what is compelling about some obscure feature. If you think something is interesting or noteworthy, tell us about it.

The prize. We cannot offer prize money or a trip to Mars, but we can promise you credit and glory. Well, maybe just credit. A few days after a puzzler image appears on this blog, we will post an annotated and captioned version as our Image of the Day. After we post the answer, we will acknowledge the first person to correctly identify the image at the bottom of this blog post. We also may recognize readers who offer the most interesting tidbits of information about the geological, meteorological, or human processes that have shaped the landscape. Please include your preferred name or alias with your comment. If you work for or attend an institution that you would like to recognize, please mention that as well.

Recent winners. If you’ve won the puzzler in the past few months, or if you work in geospatial imaging, please hold your answer for at least a day to give less experienced readers a chance.

Releasing Comments. Savvy readers have solved some puzzlers after a few minutes. To give more people a chance, we may wait 24 to 48 hours before posting comments. Good luck!

UPDATE on November 9 — The answer is a phytoplankton bloom near the Jason Islands, an archipelago off of the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands. Read more about it here. Evzen Schulc quickly identified that it was an ocean bloom, though no one managed to identify the location.

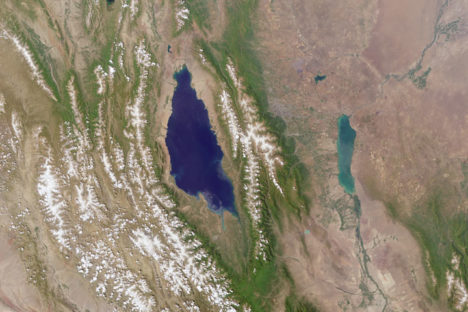

Every month on Earth Matters, we offer a puzzling satellite image. The February 2020 puzzler is above. Your challenge is to use the comments section to tell us what we are looking at, where it is, and why it is interesting.

How to answer. You can use a few words or several paragraphs. You might simply tell us the location, or you can dig deeper and explain what satellite and instrument produced the image, what spectral bands were used to create it, or what is compelling about some obscure feature. If you think something is interesting or noteworthy, tell us about it.

The prize. We cannot offer prize money or a trip to Mars, but we can promise you credit and glory. Well, maybe just credit. Roughly one week after a puzzler image appears on this blog, we will post an annotated and captioned version as our Image of the Day. After we post the answer, we will acknowledge the first person to correctly identify the image at the bottom of this blog post. We also may recognize readers who offer the most interesting tidbits of information about the geological, meteorological, or human processes that have shaped the landscape. Please include your preferred name or alias with your comment. If you work for or attend an institution that you would like to recognize, please mention that as well.

Recent winners. If you’ve won the puzzler in the past few months, or if you work in geospatial imaging, please hold your answer for at least a day to give less experienced readers a chance.

Releasing Comments. Savvy readers have solved some puzzlers after a few minutes. To give more people a chance, we may wait 24 to 48 hours before posting comments. Good luck!

The Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR) team at NASA is pleased to offer its 31st “Where on Earth?” quiz.

To participate, visit https://climate.nasa.gov/quizzes/misr_quiz_31/

When you visit that page and press “start,” you will be presented with nine multiple-choice questions (one for each of MISR’s nine cameras) about the image above. You may research the answers using any website or reference material you like. You cannot go back to previous questions, so make sure of your answer before proceeding!

The natural color image above was acquired by MISR’s vertical-viewing camera in July 2017 and represents an area about 300 kilometers by 240 kilometers (190 miles by 150 miles). Note that north is not necessarily at the top of the image.

If you answer all of the questions correctly, you will be eligible for a prize. The deadline for entries is July 18, 2019, at 4:00 p.m. Pacific Time. Note – if you try to answer on this blog, you will not be eligible for the prize, so click here to take the quiz.

The Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR) team at NASA has opened its 30th Where on Earth? quiz.

Visit http://climate.nasa.gov/quizzes/misr_quiz_30

Here’s how it works: When you press “start,” you will be presented with nine multiple-choice questions (one question for each of MISR’s nine cameras) about the area shown in the image below. You are encouraged to research the answers using any websites or reference materials you like. You cannot go back to previous questions, so make sure of your answer before proceeding to the next one. If you answer all of the questions correctly, you will have a chance to enter for a prize. The deadline for entries is 4:00 p.m. Pacific Daylight Time on August 8, 2018.

This natural color image was acquired by the vertical-viewing camera of the MISR instrument in July 2017 and represents an area of about 290 miles by 210 miles (470 kilometers by 340 kilometers). Note that north is not necessarily at the top.

The official quiz can be found at http://climate.nasa.gov/quizzes/misr_quiz_30

Every month on Earth Matters, we offer a puzzling satellite image. The March 2018 puzzler is above. Your challenge is to use the comments section to tell us what we are looking at and why this place is interesting.

How to answer. You can use a few words or several paragraphs. You might simply tell us the location. Or you can dig deeper and explain what satellite and instrument produced the image, what spectral bands were used to create it, or what is compelling about some obscure feature in the image. If you think something is interesting or noteworthy, tell us about it.

The prize. We can’t offer prize money or a trip to Mars, but we can promise you credit and glory. Well, maybe just credit. Roughly one week after a puzzler image appears on this blog, we will post an annotated and captioned version as our Image of the Day. After we post the answer, we will acknowledge the first person to correctly identify the image at the bottom of this blog post. We also may recognize readers who offer the most interesting tidbits of information about the geological, meteorological, or human processes that have shaped the landscape. Please include your preferred name or alias with your comment. If you work for or attend an institution that you would like to recognize, please mention that as well.

Recent winners. If you’ve won the puzzler in the past few months or if you work in geospatial imaging, please hold your answer for at least a day to give less experienced readers a chance to play.

Releasing Comments. Savvy readers have solved some puzzlers after a few minutes. To give more people a chance to play, we may wait between 24 to 48 hours before posting comments.

Good luck!

Each month, we try to stump you with a new EO Puzzler. If you missed the latest one, or if you just want more challenges, we have a new one from our colleagues at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The science and outreach team from the Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR) is inviting you to become a geographical detective and solve their latest mystery quiz. But this is more than just a “where is this place?” kind of quiz. You need to know some history — natural and human — to correctly answer all of the questions. Check out the quiz — based on the image below — at http://climate.nasa.gov/quizzes/misr_quiz_29.

Quiz answers will be accepted on the MISR page through 4:00 p.m. Pacific Daylight Time on June 28.

The science team behind the Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR) on NASA’s Terra satellite frequently publishes special images called stereo anaglyphs. For example, you might have seen our recent series of anaglyphs celebrating the centennial of the National Park Service. But what exactly is an anaglyph, and how is one made from MISR data?

All methods of viewing images in three dimensions rely on the fact that our two eyes see things at slightly different angles; this is what gives us depth perception. As a simple demonstration, hold a finger at a short distance from your face, and close one eye at a time. You will notice that your finger appears to be in a different place with each eye. The horizontal distance between the two versions of your finger is called the parallax. Your brain interprets the amount of parallax to tell you how far away your finger is from your face—the greater the parallax, the closer your finger!

However, your brain can also be tricked into thinking that a perfectly flat picture is actually a three-dimensional object by presenting each eye with a slightly different version of the picture. The first 3D viewing technology was the stereoscope, originally invented by Sir Charles Wheatstone in 1838. The stereoscope takes two images viewed from slightly different angles and mounts them next to each other. The photos are viewed using fixed lenses that fool the brain into thinking that it is looking at one picture. Stereoscopes worked well, but their major drawback was that they could only be used by one person at a time.

In 1858, Joseph D’Almeida, a French physics professor, invented a method of showing stereoscopic images to many people at once using a lantern projector equipped with red and blue filters. The viewers wore red and blue goggles. Later, Louis Du Haron adapted this technique to allow anaglyphs to be printed and viewed on paper. In 1889, William Freise-Green created the first anaglyphic motion picture. These early 3D movies were nicknamed “plastigrams” and were very popular by the 1920s.

At the most basic level, anaglyphs work by superimposing images taken from two angles. The two images are printed in different colors, usually red and cyan. The viewer needs glasses with lenses in the same colors. The lenses are needed to filter out the unwanted image for each eye. So, if the image for the right eye is printed in red, the image can be seen through the cyan lens placed over the right eye, but not through the red lens over the left eye, and vice versa. The brain, seeing two different pictures through each eye, interprets this as a three-dimensional scene.

The reason why the MISR instrument can be used to make anaglyphs is because it has nine cameras, each fixed to point at a different angle. Therefore, as MISR passes over a particular feature on Earth, it captures nine images spanning a range of 140 degrees (diagram above). Any two of these images can be combined to make an anaglyph. The greater the angular difference between the images, the greater the resulting 3D effect; however, if the angular difference is too great, the brain will be unable to interpret the image.

Anaglyphs made with MISR must be rotated so that the north-south direction is roughly horizontal. Though this is inconvenient — we are used to viewing the Earth with north at the top — it is necessary because Terra flies from north to south, and MISR’s cameras are aligned to take images along that track. Therefore, the angular difference between the images is in the north-south direction. Since our eyes are arranged horizontally, the angular difference between the anaglyph images must be horizontal as well.

You can see this by comparing two versions of an anaglyph of Denali, Alaska (below). In the version with north upwards (left), the 3D effect does not work. But when the image is rotated so that north is to the left, suddenly the mountains pop out.

Anaglyphs are useful for science because they allow us to intuitively understand the three-dimensional structure of things like hurricanes and smoke plumes. For example, examine the three-panel image of Typhoon Nepartak below. (All three images have been rotated so north is to the left).

In the top, single-angle image, the eye of the storm appears to be quite deep due to the shadows, but otherwise it is difficult to determine how high the clouds are. Compare this to the middle image, which shows the results from MISR’s cloud top height product; it uses a computer algorithm to compare the data from multiple cameras and determine the geometry of the clouds. Now we can tell that clouds in the central part of the storm are very high (except for the eye), while the spiral cloud bands are slightly lower and there are very low clouds between the arms. However, understanding this data set requires us to interpret the color key and have at least a rudimentary idea of how 16 kilometers compares to 4 kilometers.

Now put on your red-blue glasses* and look at the anaglyph in the third image. All of the features are immediately understood by our brains. While it takes a few minutes (or paragraphs) of explanation to introduce a first-time viewer to MISR datasets, the red-blue glasses make it possible to enjoy the same experience with a simple image. This is why anaglyphs make great tools for scientists as well as for sharing unique views of Earth’s features with the public.

Editor’s note: If you don’t have a pair of red-blue glasses, this page lists companies that sell them. Or if you can find some red and blue plastic wrap, you can make your own. The instructions are here.