Fire on Bellandur Lake on January 19, 2018. Photo by pee vee.

In Bengaluru, India, one of the city’s lakes is so polluted with sewage, trash, and industrial chemicals that it has an alarming habit of catching on fire. As recently as January 19, 2018, fire broke out on Bellandur Lake and burned for seven hours.

The same lake is notorious for churning up large amounts of white foam that has, at times, spilled from the lake and enveloped nearby streets, cars, and bridges. The water is so polluted that it can’t be used for drinking or bathing or even irrigation.

Bellandur Lake is not the only lake in Bengaluru with water quality problems. During a recent check, not one of the hundreds of lakes that the city tested was clean enough to be used for drinking or bathing.

Foamy water flowing into Bellandur Lake. Photo by Kannon B.

I point this out on World Water Day to underscore that Bengaluru’s water woes, though extreme, are not particularly uncommon. According to the United Nations, a quarter of all people on the planet lack access to safely managed drinking water, and 40 percent of people live in areas where water scarcity is a problem. Roughly 80 percent of wastewater flows back into ecosystems untreated. Even in the United States, tens of millions of people may be exposed to unsafe drinking water, according to one recently published study.

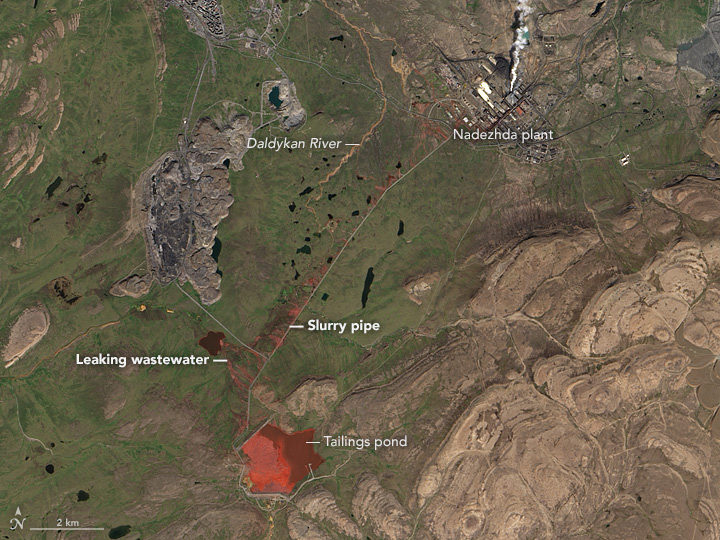

Even in the course of reporting for this website from a satellite perspective, we see signs of trouble. Capetown was on the verge of running out of water in February 2018. Drought pushed São Paulo’s reservoirs to near empty in recent years. The GRACE satellites have observed rapid depletion of groundwater in several critical aquifers. On more than one occasion, we have reported on rainbow-colored escaped mine tailings contaminating waterways.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Learn more about the image here.

To push back against such problems, NASA’s Earth Science Division, and particularly its applied sciences program, is doing what it can to marshal the agency’s resources to make countries aware of what NASA resources are available to monitor and reduce the impact of water-related problems.

Learn more about the Sustainable Development Goals. Image by the United Nations.

As one piece of its water program, NASA scientists and staff are working with the United Nations to highlight key NASA datasets, tools, and satellite-based monitoring capabilities that may help countries meet the 17 sustainable development goals established by the international body. Goal number 6—that countries ensure the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all—has been a particular focus of the NASA teams.

NASA and NOAA satellites collect several types of data that may be useful for water management. Sensors such as the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) and the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) collect daily data and images of water bodies around the planet that can be used to track the number and extent of lakes and reservoirs.

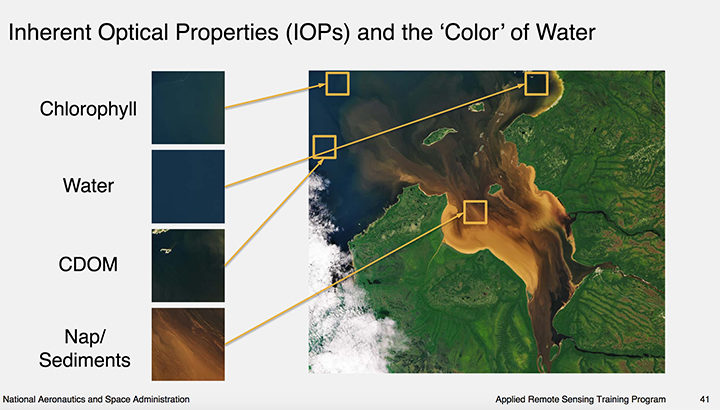

Image courtesy of this NASA ARSET presentation. Learn more about the image here.

The same sensors collect information about water color, which scientists use to detect sediment, chlorophyll-a (a product of phytoplankton and algae blooms), colored dissolved organic matter (CDOM), and other indicators of water quality.

The strength of MODIS and VIIRS is that these sensors collect daily imagery; the downside is that the data is relatively coarse. However, another family of satellites, Landsat, carries sensors that provide more than 10 times as much detail.

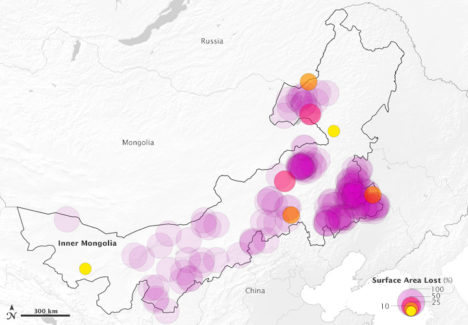

The combination of information from multiple satellites collected over time can be powerful. For instance, as we reported previously, a team of scientists based in China used decades of Landsat data to track a 30 percent decrease in the total surface area of lakes in Inner Mongolia between the 1980s and 2010. The scientists attributed the losses to warming temperatures, decreased precipitation, and increased mining and agricultural activity.

This map above depicts 375 lakes within Inner Mongolia that experienced a loss in water surface area between 1987-2010. The large, purple circles indicate a complete loss of water. Learn more about the map here.

Meanwhile, one of NASA’s scientists, Nima Pahlevan, is in the process of building an early warning system based on Landsat and Sentinel-2 data that will be used to alert water managers in near-real time when satellites detect high levels of chlorophyll-a, an indicator that harmful algal blooms could be present. While some blooms are harmless, outbreaks of certain types of organisms lead to fish kills and dangerous contamination of seafood. His team is working on a prototype system for Lake Mead in Nevada (see below), Indian River Lagoon in Florida, and certain reservoirs in Oregon. Eventually, he hopes to have a tool available that can be used globally.

“The idea is that we can get the information to water managers quickly about where satellites are seeing suspicious blooms, and then folks on the ground will know where to test water to determine if there’s a harmful algae bloom,” said Pahvalen. “We’re not suggesting that satellites can replace on-the-ground sampling, but they can be a great complement and make that work much work more efficient and less costly.”

To learn more about how satellites can be used to aid in the monitoring of water quality, see this workshop report and harmful algal bloom training module from NASA’s ARSET program.