Cape Town—a cosmopolitan city of 3.7 million people on South Africa’s western coast—is on the verge of running out of water. According to the city’s mayor, if current consumption patterns continue then drinking water taps will be turned off in April and people will have to start procuring water from one of 200 collection points throughout the city.

With key reservoirs standing at precariously low levels, the city forecasts that this so-called Day Zero will happen on April 12, 2018, though the exact date will depend on the weather and on consumption patterns in the coming months. The rainy season normally runs from May to September.

Cape Town’s six major reservoirs can collectively store 898,000 megaliters (230 billion gallons) of water, but they held just 26 percent of that amount as of January 29, 2018. Theewaterskloof Dam—the largest reservoir and the source of roughly half of the city’s water—is in the worst condition, with the water level at just 13 percent of capacity.

In practical terms, the amount of available water is even less than this number suggests because the last 10 percent of water in a reservoir is difficult to use. According to Cape Town’s disaster plan, Day Zero will happen when the system’s stored water drops to 13.5 percent of capacity. At that point, the water that remains will go to hospitals and certain settlements that rely on communal taps. Most people in the city will be left without tap water for drinking, bathing, or other uses.

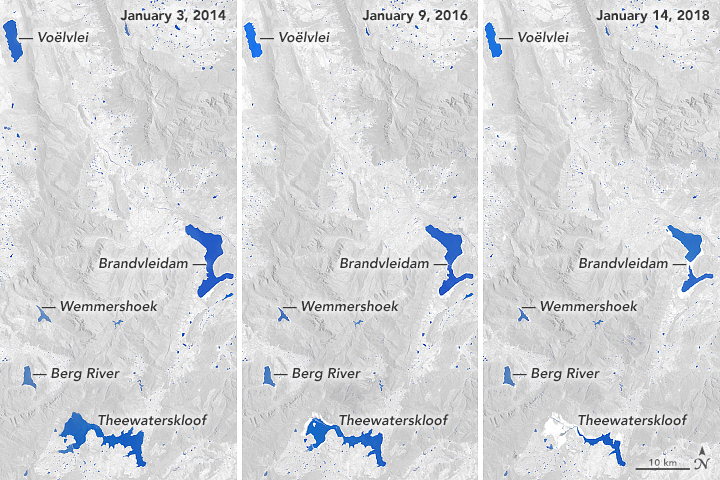

The animated image at the top of the page shows how dramatically Theewaterskloof has been depleted between January 2014 and January 2018. The extent of the reservoir is shown with blue; non-water areas have been masked with gray in order to make it easier to distinguish how the reservoir has changed. Theewaterskloof was near full capacity in 2014. During the preceding year, the weather station at Cape Town airport tallied 682 millimeters (27 inches) of rain (515 mm is normal), making it one of the wettest years in decades. However, rains faltered in 2015, with just 325 mm falling. The next year, with 221 mm, was even worse. In 2017, the station recorded just 157 mm of rain.

This trio of images shows how the three successive dry years took a toll on Cape Town’s water system. Voëlvlei, the second largest reservoir, has dropped to 18 percent of capacity. Some of the smaller reservoirs like the Berg River and Wemmershoek are still relatively full, but they store only a small fraction of the city’s water. One of the largest reservoirs in the area—Brandvlei—does not supply water to Cape Town; its water is used by farmers for irrigation.

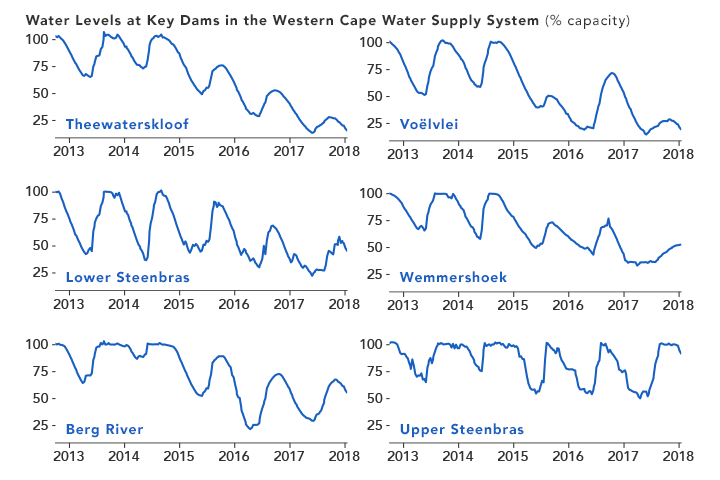

The line chart below details how water levels in the six key reservoirs have changed since 2013. Though the reservoirs are replenished each winter as the rains arrive, the trend at almost all of them has been downward. The one exception is Upper Steenbras, which holds about 4 percent of the city’s water and has been kept full because it is also used to generate electricity during peak demand. Also, the city is likely drawing down the largest reservoirs first to minimize how much water is lost to evaporation.

Piotr Wolski, a hydrologist at the Climate Systems Analysis Group at the University of Cape Town, has analyzed rainfall records dating back to 1923 to get a sense of the severity of the current drought compared to historical norms. His conclusion is that back-to-back years of such weak rainfall (like 2016-17) typically happens about once just every 1,000 years.

Population growth and a lack of new infrastructure has exacerbated the current water shortage. Between 1995 and 2018, the Cape Town’s population swelled by roughly 80 percent. During the same period, dam storage increased by just 15 percent.

The city did recently accelerate development of a plan to increase capacity at Voëlvlei Dam by diverting winter rainfall from the Berg River. The project had been scheduled for completion in 2024, but planners are now targeting 2019. The city is also working to build a series of desalination plants and to drill new groundwater wells that could produce additional water.

In the meantime, Cape Town authorities have put tight restrictions on residential water usage. New guidelines ban all use of drinking water for non-essential purposes, while urging people to use less than 50 liters (13 gallons) of water per person per day.

While many people are preparing for the water turn off in April, some observers see signs that Day Zero could still be averted. Kevin Winter, a hydrologist at the University the Cape Town, notes that by the end of January farmers will no longer be drawing from the system, meaning the water that remains may last a little longer. Overall, the agricultural sector uses about half of the water in the system.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and water level data from South Africa's Department of Water and Sanitation. Story by Adam Voiland.