NASA Earth Observatory readers may recognize this image of a long trail of clouds — an atmospheric river — reaching across the Pacific Ocean toward California. It appeared first as an Image of the Day about how these moisture superhighways fueled a series of drought-busting rain and snow storms.

NASA Earth Observatory readers may recognize this image of a long trail of clouds — an atmospheric river — reaching across the Pacific Ocean toward California. It appeared first as an Image of the Day about how these moisture superhighways fueled a series of drought-busting rain and snow storms.

More recently, we were pleased to see that image on the cover of the Fourth National Climate Assessment — a major report issued by the U.S. Global Research Program. That image was one of many from Earth Observatory that appeared in the report. Since the authors did not give much background about the images, here is a quick rundown of how they were created and how they fit with some of the key points on our changing climate.

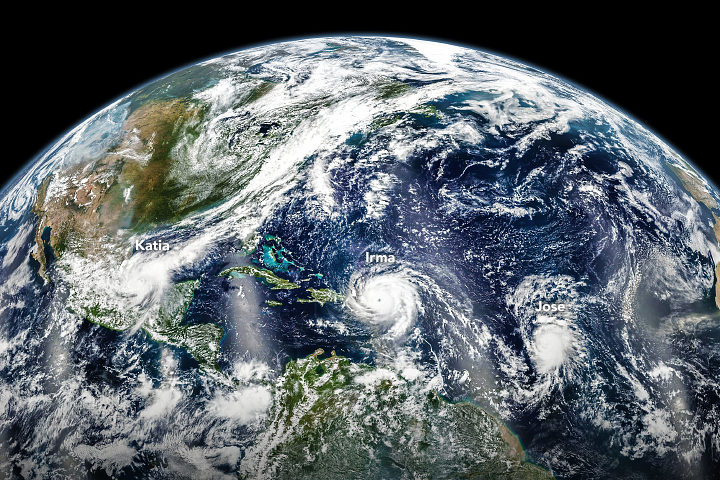

Hurricanes in the Atlantic

Found in Chapter 1: Our Globally Changing Climate

What the image shows:

Three hurricanes — Katia, Irma, and Jose — marching across the Atlantic Ocean on September 6, 2017.

What the report says about tropical cyclones and climate change:

The frequency of the most intense hurricanes is projected to increase in the Atlantic and the eastern North Pacific. Sea level rise will increase the frequency and extent of extreme flooding associated with coastal storms, such as hurricanes.

How the image was made:

The Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the Suomi NPP satellite collected the data. Earth Observatory staff combined several scenes, taken at different times, to create this composite. Original source of the image: Three Hurricanes in the Atlantic

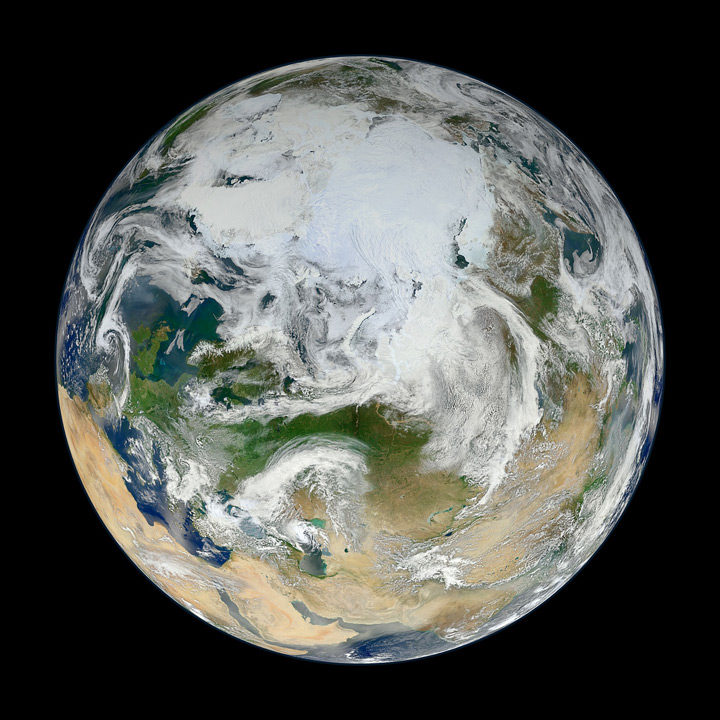

The North Pole

Found in Chapter 2: Physical Drivers of Climate Change

What the image shows:

Clouds swirl over sea ice, glaciers, and green vegetation in the Northern Hemisphere, as seen on a spring day from an angle of 70 degrees North, 60 degrees East.

What the report says about climate change and the Arctic:

Over the past 50 years, near-surface air temperatures across Alaska and the Arctic have increased at a rate more than twice as fast as the global average. It is very likely that human activities have contributed to observed Arctic warming, sea ice loss, glacier mass loss, and a decline in snow extent in the Northern Hemisphere.

How it was made:

Ocean scientist Norman Kuring of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center pieced together this composite based on 15 satellite passes made by VIIRS/Suomi NPP on May 26, 2012. The spacecraft circles the Earth from pole to pole, so it took multiple passes to gather enough data to show an entire hemisphere without gaps. Original source of the image: The View from the Top

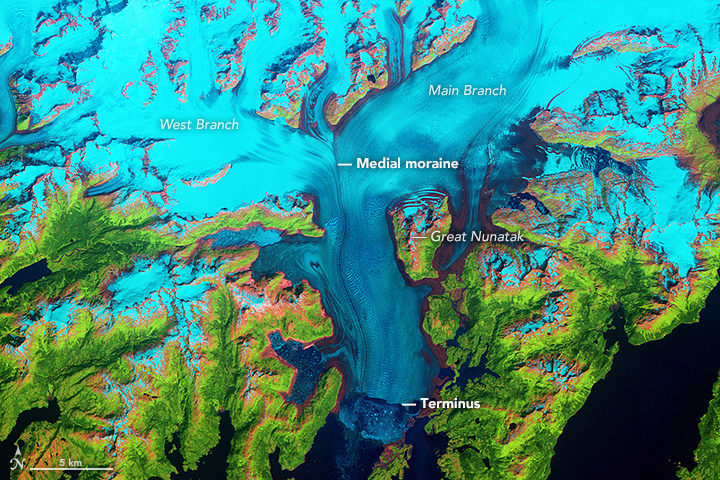

Columbia Glacier

Found in Chapter 3: Detection and Attribution of Climate Change

What the image shows:

Columbia Glacier in Alaska, one of the most rapidly changing glaciers in the world.

What the report says about Alaskan glaciers and climate change:

The collective ice mass of all Arctic glaciers has decreased every year since 1984, with significant losses in Alaska.

How the image was made:

NASA Earth Observatory visualizers made this false-color image based on data collected in 1986 by the Thematic Mapper on Landsat 5. The image combines shortwave-infrared, near-infrared, and green portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. With this combination, snow and ice appears bright cyan, vegetation is green, clouds are white or light orange, and open water is dark blue. Exposed bedrock is brown, while rocky debris on the glacier’s surface is gray. Original source of the image: World of Change: Columbia Glacier

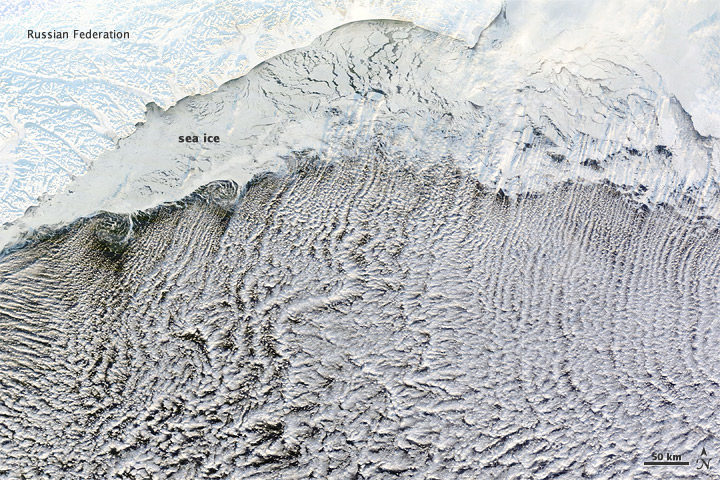

Cloud Streets

Found in: Intro to Chapter 4: Climate Models, Scenarios, and Projections

What the image shows:

Sea ice hugging the Russian coastline and cloud streets streaming over the Bering Sea.

What the report says about clouds and climate change:

Climate feedbacks are the largest source of uncertainty in quantifying climate sensitivity — that is, how much global temperatures will change in response to the addition of more greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.

How it was made:

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite captured this natural-color image on January 4, 2012. The LANCE/EOSDIS MODIS Rapid Response Team generated the image, and NASA Earth Observatory staff cropped and labeled it. Original source of the image: Cloud streets over the Bering Sea

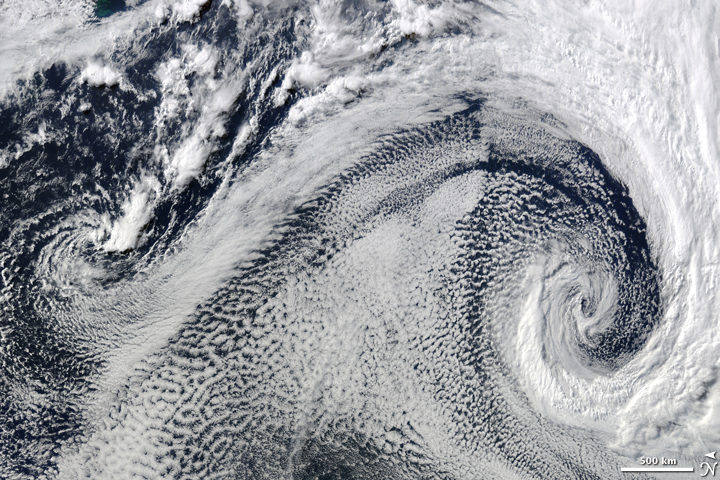

Extratropical Cyclones

Found in Intro to Chapter 5: Large-scale circulation and climate variability

What it shows:

Two extratropical cyclones, the cause of most winter storms, churned near each other off the coast of South Africa in 2009.

What the report says about extratropical storms and climate change:

There is uncertainty about future changes in winter extratropical cyclones. Activity is projected to change in complex ways, with increases in some regions and seasons and decreases in others. There has been a trend toward earlier snowmelt and a decrease in snowstorm frequency on the southern margins of snowy areas. Winter storm tracks have shifted northward since 1950 over the Northern Hemisphere.

How the image was made:

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite captured this natural-color image. The LANCE/EOSDIS MODIS Rapid Response Team generated the image and NASA Earth Observatory staff cropped and labeled it. Original source of the image: Cyclonic Clouds over the South Atlantic Ocean

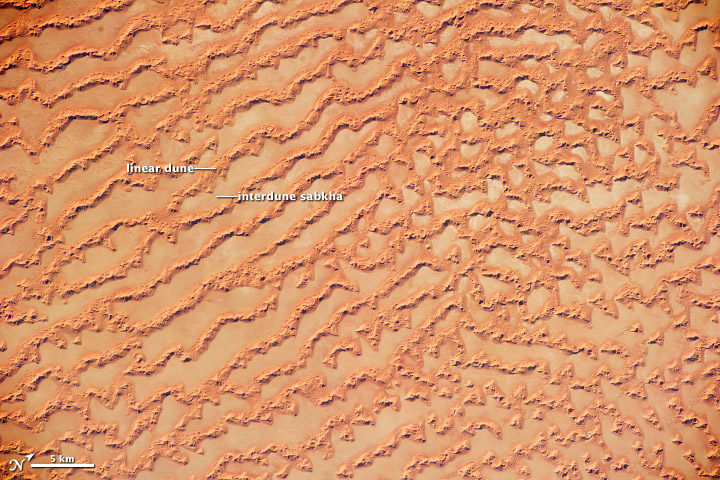

Sea of Sand

Found in: Chapter 6: Temperature Changes in the United States

What the image shows: Large, linear sand dunes alternating with interdune salt flats in the Rub’ al Khali in the Sultanate of Oman.

What the report says about drought, dust storms, and climate change:

The human effect on droughts is complicated. There is little evidence for a human influence on precipitation deficits, but a lot of evidence for a human fingerprint on surface soil moisture deficits — starting with increased evapotranspiration caused by higher temperatures. Decreases in surface soil moisture over most of the United States are likely as the climate warms. Assuming no change to current water resources management, chronic hydrological drought is increasingly possible by the end of the 21st century. Changes in drought frequency or intensity will also play an important role in the strength and frequency of dust storms.

How it was made: An astronaut on the International Space Station took the photograph with a Nikon D3S digital camera using a 200 millimeter lens on May 16, 2011. Original source of the image: Ar Rub’ al Khali Sand Sea, Arabian Peninsula

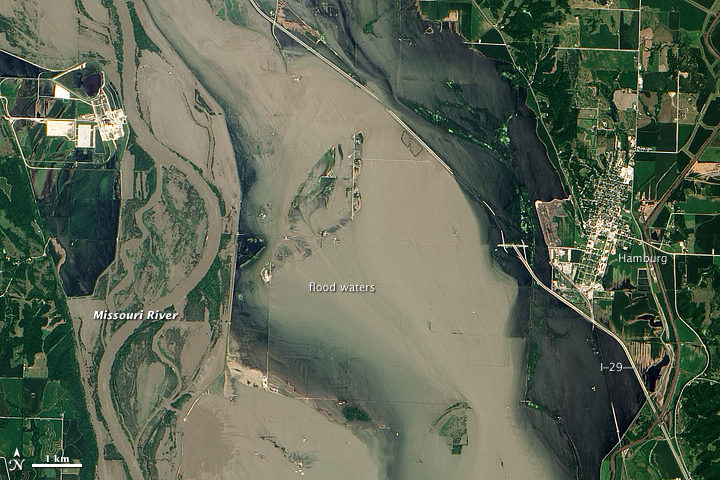

Flooding on the Missouri River

Found in Chapter 7: Precipitation Change in the United States

What the image shows:

Sediment-rich flood water lingering on the Missouri River in July 2011.

What the report says about precipitation, floods, and climate change:

Detectable changes in flood frequency have occurred in parts of the United States, with a mix of increases and decreases in different regions. Extreme precipitation, one of the controlling factors in flood statistics, is observed to have generally increased and is projected to continue to do. However, scientists have not yet established a significant connection between increased river flooding and human-induced climate change.

How the image was made:

The Advanced Land Imager (ALI) on NASA’s Earth Observing-1 (EO-1) satellite captured the data for this natural-color image. NASA Earth Observatory staff processed, cropped, and labeled the image. Original source of the image: Flooding near Hamburg, Iowa

Smoke and Fire

Found in Chapter 8: Droughts, Floods, and Wildfires

What the image shows:

Smoke streaming from the Freeway fire in the Los Angeles metro area on November 16, 2008.

What the report says about wildfires and climate change:

The incidence of large forest fires in the western United States and Alaska has increased since the early 1980s and is projected to further increase as the climate warms, with profound changes to certain ecosystems. However, other factors related to climate change — such as water scarcity or insect infestations — may act to stifle future forest fire activity by reducing growth or otherwise killing trees.

How it was made: The MODIS Rapid Response Team made this image based on data collected by NASA’s Aqua satellite. Original source of the image: Fires in California

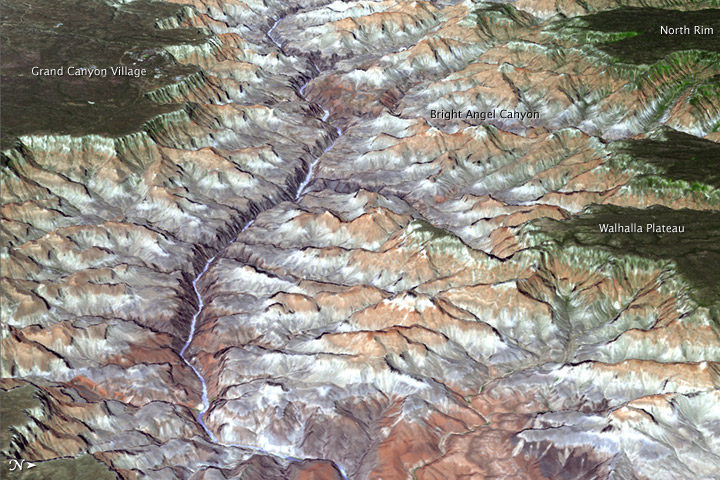

The Colorado River and Grand Canyon

Found in Chapter 10: Changes in Land Cover and Terrestrial Biogeochemistry

What the image shows:

The Grand Canyon in northern Arizona.

What the report says about climate change and the Colorado River:

The southwestern United States is projected to experience significant decreases in surface water availability, leading to runoff decreases in California, Nevada, Texas, and the Colorado River headwaters, even in the near term. Several studies focused on the Colorado River basin showed that annual runoff reductions in a warmer western U.S. climate occur through a combination of evapotranspiration increases and precipitation decreases, with the overall reduction in river flow exacerbated by human demands on the water supply.

How the image was made:

On July 14, 2011, the ASTER sensor on NASA’s Terra spacecraft collected the data used in this 3D image. NASA Earth Observatory staff made the image by draping an ASTER image over a digital elevation model produced from ASTER stereo data. Original source of the image: Grand New View of the Grand Canyon

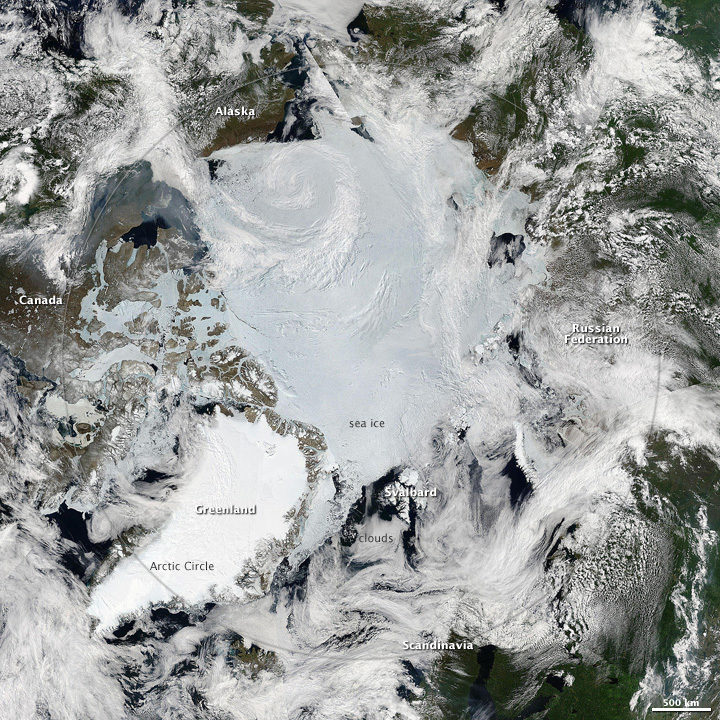

Arctic Sea Ice

Found in Chapter 11: Arctic Changes and their Effects on Alaska and the Rest of the United States

What the image shows: A clear view of the Arctic in June 2010. Clouds swirl over sea ice, snow, and forests in the far north.

What the report says about sea ice and climate change: Since the early 1980s, annual average Arctic sea ice has decreased in extent between 3.5 percent and 4.1 percent per decade, become 4.3 to 7.5 feet (1.3 and 2.3 meters) thinner. The ice melts for at least 15 more days each year. Arctic-wide ice loss is expected to continue through the 21st century, very likely resulting in nearly sea ice-free late summers by the 2040s.

How it was made: Earth Observatory staff used data from several MODIS passes from NASA’s Aqua satellite to make this mosaic. All of the data were collected on June 28, 2010. Original source of the image: Sunny Skies Over the Arctic

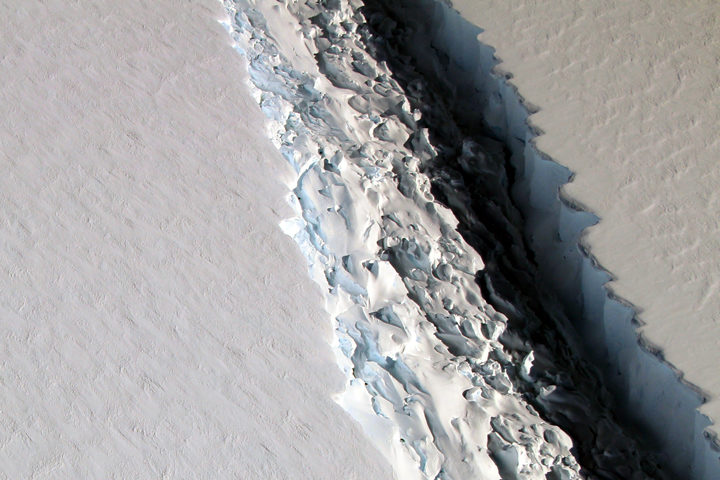

Crack in the Larsen C Ice Shelf

Found in Chapter 12: Sea Level Rise

What the image shows:

This photograph shows a rift in the Larsen C Ice Shelf as observed from NASA’s DC-8 research aircraft. An iceberg the size of Delaware broke off from the ice shelf in 2017.

What the report says about ice shelves in Antarctica and climate change?

Floating ice shelves around Antarctica are losing mass at an accelerating rate. Mass loss from floating ice shelves does not directly affect global mean sea level — because that ice is already in the water — but it does lead to the faster flow of land ice into the ocean.

How it was made:

NASA scientist John Sonntag took the photo on November 10, 2016, during an Operation IceBridge flight. Original source of the image: Crack on Larsen C

The Gulf of Mexico

Found in Chapter 13: Ocean Acidification and Other Changes

What the image shows:

Suspended sediment in shallow coastal waters in the Gulf of Mexico near Louisiana.

What the report says about the Gulf of Mexico:

The western Gulf of Mexico and parts of the U.S. Atlantic Coast (south of New York) are currently experiencing significant sea level rise caused by the withdrawal of groundwater and fossil fuels. Continuation of these practices will further amplify sea level rise.

How the image was made:

The MODIS instrument on NASA’s Aqua satellite captured this natural-color image on November 10, 2009. Original source of the image: Sediment in the Gulf of Mexico

Farmland in Virginia

Found in Appendix D

What the image shows:

A fall scene showing farmland in the Page Valley of Virginia, between Shenandoah National Park and Massanutten Mountain.

What the report says about farming and climate change:

Since 1901, the consecutive number of frost-free days and the length of the growing season have increased for the seven contiguous U.S. regions used in this assessment. However, there is important variability at smaller scales, with some locations actually showing decreases of a few days to as much as one to two weeks. However, plant productivity has not increased, and future consequences of the longer growing season are uncertain.

How the image was made: On October 21, 2013, the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 captured a natural-color image of these neighboring ridges. The Landsat image has been draped over a digital elevation model based on data from the ASTER sensor on the Terra satellite. Original source of the image: Contrasting Ridges in Virginia

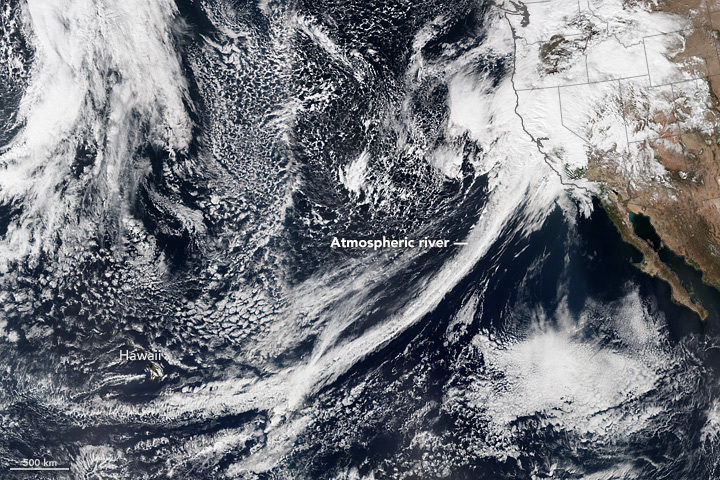

Atmospheric River

Found on the Cover and Executive Summary

What the image shows: A tight arc of clouds stretching from Hawaii to California, which is a visible manifestation of an atmospheric river of moisture flowing into western states.

What the report says about atmospheric rivers and climate change:

The frequency and severity of land-falling atmospheric rivers on the U.S. West Coast will increase as a result of increasing evaporation and the higher atmospheric water vapor content that occurs with increasing temperature. Atmospheric rivers are narrow streams of moisture that account for 30 to 40 percent of the typical snow pack and annual precipitation along the Pacific Coast and are associated with severe flooding events.

How it was made: On February 20, 2017, the VIIRS on Suomi NPP captured this natural-color image of conditions over the northeastern Pacific. NASA Earth Observatory data visualizers stitched together two scenes to make the image. Original source of the image: River in the Sky Keeps Flowing Over the West

With thousands of homes threatened by intense wildfires burning in southern California, NASA Earth Observatory checked in with Jet Propulsion Laboratory scientist Natasha Stavros to learn more about the destructive blazes.

Earth Observatory (EO): Why have these fires been so fast-moving and destructive? Are fierce Santa Ana winds the key factor? Are anomalous temperatures, rainfall, ENSO conditions, bark beetle activity, or other factors playing an important role?

There are absolutely other factors. Santa Ana winds definitely played a role in spreading the fires, but the late fire season is a more complex story. Last year, we had a lot of heavy rains, and this increased fuel connectivity by enabling grasses and annual shrubs to flourish (hence the green hills last spring). However, we had a lot of record-breaking heat waves this year.

In fact, a recent study we conducted with NASA DEVELOP and the National Park Service in the Santa Monica Mountains showed that the number of days over 95 degrees Fahrenheit stressed established vegetation and contributed to massive die-off. Even though the drought is over, the trees are still recovering from the stress of reduced water availability for such an extended period. They are in a fragile state and their defenses are down. This means that they are even more susceptible to infestation, mortality, and ultimately fire danger.

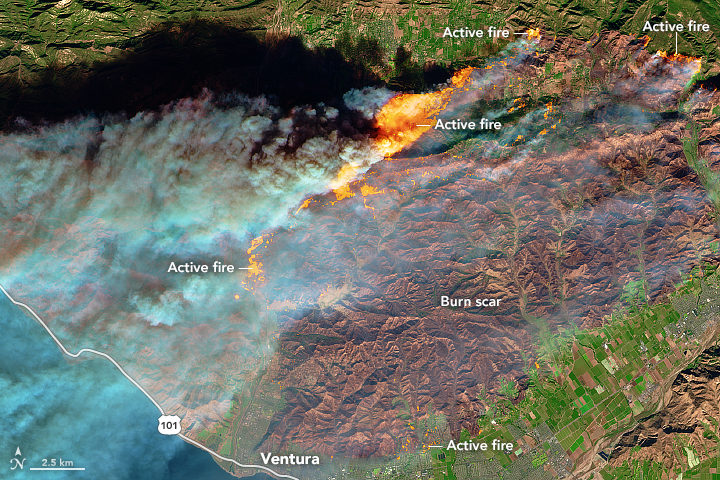

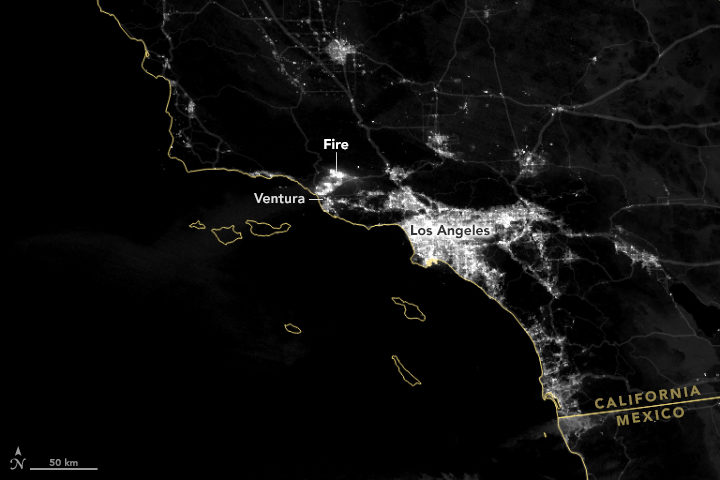

EO: We have published MODIS (top of the page), Sentinel-2 (below), and nighttime VIIRS (bottom of the page) satellite imagery of these fires. Is there anything that you find particularly interesting or notable about these images?

To me, the noteworthy thing is that the plume is going over the ocean and not the continental United States (as we saw earlier this year). This has to do with the Santa Ana winds coming from the desert and pushing particulates, ozone, carbon monoxide, and other toxic pollutants away from where people live.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2017) processed by the European Space Agency.

As for the Sentinel-2 image, this is a great shot in that it really shows the value of remote sensing in monitoring fire. Flames that look like that are tens of meters tall. The flame length is proportional to the heat released from the flame, so these fires are very hot. Just like you would not want to stand too close to a bonfire with flames tens of meters tall, fire management does not want to put personnel in the path of those flames.

Images like these and fire behavior models help inform how we think the fire will move across the landscape. There is still a lot we do not know; our models are based on what we do know, so as fires become more intense, the models do not work as well, so this is an area of active research.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens using VIIRS day-night band data from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership.

EO: Is there anything to say about how these fires fit into longer term trends and/or changing climate patterns?

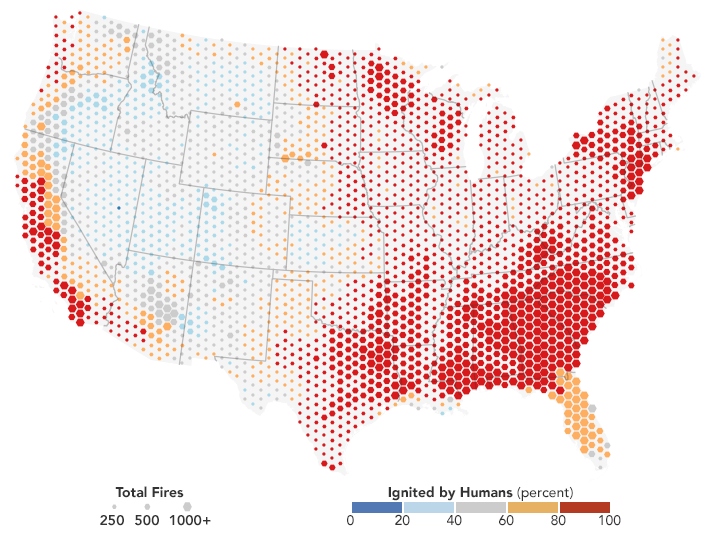

Fire regimes are changing. There is no question about that, and there are a lot of things contributing to it: climate change, a century of fire exclusion, and a growing wildland urban interface (WUI). As we move into the future, we expect there to be an increase in very large fire events. Also, and this is relevant for the events happening now, there will be longer fire seasons. Also, note that many of the fires that ignite close to where people live are actually caused by people. This is particularly true in Southern California.

As we move forward, we need to think about how to support smart fire management practices. By that I mean: what can we proactively do to reduce fire risk (i.e. the threat to valuable resources)?

Most fires on the coasts are lit by people. NASA Earth Observatory map by Joshua Stevens, using fire data courtesy of Balch, J. et al. (2017).

EO: What about JPL’s response to these fires? I was intrigued by the megafire project described here. Will your group be responding to this fire in any way?

We just received approval from NASA Headquarters to fly the Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer (AVIRIS) over these fires. This sensor has been useful for investigating fuel load type and subsequent effects on emission types, fire behavior, and post-fire analysis (e.g., safety, erosion, area burned, fire severity or the amount of environmental change caused the fire, etc.) and is often analyzed in interagency and federal-academic coordination to improve our understanding of fire.

Another effort to support fire management includes work being done from JPL in coordination with the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) to help them develop metrics of fire danger using NASA satellites that provide hydrologic variables (e.g., soil moisture and vapor pressure deficit—the difference between the amount of moisture in the air vs how much it can hold). These metrics have a one-month forecast to help allocate fire management resources nationally, which is particularly important as our fire seasons extend throughout the year in multiple places at the same time.

Natasha Stavros. Image courtesy of N. Stavros.