Many readers were convinced that our June Puzzler (image above) showed Nazca lines in southern Peru. There certainly were lines in the image, but they were located about 10,000 kilometers (6,000 miles) away from Peru on a plateau in southern Libya. While the Nazca lines were probably created for religious purposes, the grid lines in Libya had a very different raison d’être: oil exploration.

As Stefano correctly noted at 12:26 p.m. on June 23, the lines were tracks left over from a seismic survey. While a layer of rocks, gravel, and ancient stone tools carpet most of the plateau, lines of large “thumper” trucks that use a vibrating metal plate to press down against the ground likely created the grid pattern. When they drove around prospecting the area with seismic sensors, the trucks kicked up a very fine layer of dust that was lighter brown than the rest of the surface. Less than two hours after Stefano weighed in, Miles Saunders explained much of this.

Nazca lines in southern Peru. Read more about them here.

Twenty minutes later, Franco B. weighed in with some more key details. “This looks like geophysical prospection lines in some oil field in an arid zone, each line would be a succession of geophones placed in order to make seismic sections. The scattered dots are probably oil wells. The combination of lines at 90º allows to make very detailed 3D maps of the geological structures in depth, in order to improve the oil and gas exploration. All this overlays on what looks like an intermittent dendritic drainage pattern, evidence of the arid climate,” he said.

To get a sense of how the “thumper” trucks work, check out the video below from Maurin Media.

Here is a view of what the tracks look like on the ground.

Meanwhile, twelve minutes before Stefano mentioned seismic lines on our blog, Kaye Simonson noted on our Facebook page that the grid was related to seismographs. About ten minutes later, Chris Leonard posted the exact coordinates on Facebook. By that afternoon, Leonard had figured out that the image featured seismic grid lines related to oil exploration. He worked it out by locating an archaeological study published in PLOS One that included the telling figure shown below. As the authors of that paper explain, the top part of the figure (a) shows the location of the grid lines that were laid out for oil exploration. The middle part (b) shows where archaeologists discovered stone tools (lithics) during a sweep before the seismic survey. A white circle indicates the presence of tools; larger circles indicate a higher density of stone tools. The bottom part (c) shows a more detailed view of a small portion of the plateau.

To learn more about the area, read our June 27, 2015, Image of the Day. Thanks to all of you who participated, and a big congratulations to the winners!

Image from Foley & Lahr, 2015

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) for 2010-2012 with dust and sea salt included. Visualization by Josh Stevens. Data from van Donkelaar et al.

Fine particulate matter (2.5) concentration for 2010-2012 without dust and sea salt included. Data from van Donkelaar et al.

If you saw our June 22 Image of the Day with global maps of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), you may have noticed large concentrations over the Sahara Desert and the Arabian Peninsula. With vast deserts in these areas, it’s not a surprise that the satellites detected so many particulates. Winds regularly send plumes of dust blowing over the region and even to Europe and the Americas.

However, it isn’t clear how damaging dust particles are to human health in comparison to other types of fine aerosol particles (such as those produced by burning fossil fuels or biomass burning). Several teams of epidemiologists have looked for associations between outbreaks of Saharan dust and health problems, but the results have been mixed. A literature review published in 2012 summarized the state of the science this way: “The association of fine particles PM2.5, with total or cause-specific mortality is not significant during Saharan dust intrusions. However, regarding coarser fractions PM10 and PM2.5-10, an explicit answer cannot be given. Some of the published studies state that they increase mortality during Sahara dust days while other studies find no association between mortality and PM10 or PM2.5-10. The main conclusion of this review is that health impacts of Saharan dust outbreaks needs to be further explored.”

Since dust is natural and may not have significant effects on human health, the team of Dalhousie University scientists who developed the global PM2.5 exposure maps prepared two versions of their data. One shows total PM2.5 concentration (top map above) globally; the other shows PM2.5 excluding contributions from dust and sea salt (bottom map). Notice how much less PM2.5 appears in northern Africa when dust is excluded.

To get a sense of how PM2.5 concentration (excluding dust and sea salt) has changed between 2000 and 2010, see the map below. Notice that while PM2.5 has decreased over North America and Europe, it has increased over Asia. To read more about what is driving these trends, read this story. To learn more about the data used to create these maps, visit this website.

Areas where PM2.5 concentration has increased between 1998 and 2012 are shown with shades of red. Decreases are shown with shades of blue. Data from van Donkelaar et al.

Every month on Earth Matters, we offer a puzzling satellite image. The June 2015 puzzler is above. Your challenge is to use the comments section to tell us what part of the world we are looking at, when the image was acquired, what the image shows, and why the scene is interesting.

How to answer. Your answer can be a few words or several paragraphs. (Try to keep it shorter than 200 words). You might simply tell us what part of the world an image shows. Or you can dig deeper and explain what satellite and instrument produced the image, what spectral bands were used to create it, or what is compelling about some obscure speck in the far corner of an image. If you think something is interesting or noteworthy, tell us about it.

The prize. We can’t offer prize money, but, we can promise you credit and glory (well, maybe just credit). Roughly one week after a puzzler image appears on this blog, we will post an annotated and captioned version as our Image of the Day. In the credits, we’ll acknowledge the person who was first to correctly ID the image. We’ll also recognize people who offer the most interesting tidbits of information about the geological, meteorological, or human processes that have played a role in molding the landscape. Please include your preferred name or alias with your comment. If you work for or attend an institution that you want us to recognize, please mention that as well.

Recent winners. If you’ve won the puzzler in the last few months or work in geospatial imaging, please sit on your hands for at least a day to give others a chance to play.

Releasing Comments. Savvy readers have solved some of our puzzlers after only a few minutes or hours. To give more people a chance to play, we may wait between 24-48 hours before posting the answers we receive in the comment thread.

Good luck!

Congratulations to reader John Radford for being the first to solve our May 2015 puzzler. As John noted: “It is East Java looking across Surabaya towards Bali and further islands. The numerous lights in the Java Sea must be mostly fishing boats though the cluster dead center may be partly Pulau Kangean lights. The yellowish isolated light about 3/4 of the way up and left of center must be Makassar. The white flash to its left probably is lightning strike onto West Sulawesi proper. The entire landscape is volcanic in origin, Indonesia being the most volcanically active country in the world, at the junction of 4 tectonic plates.” Congratulations also to Claudia for being the first reader who noted it was a photograph taken by an astronaut on the International Space Station. The perspective isn’t exactly the same, but below is a view of the same general area from Google Earth.

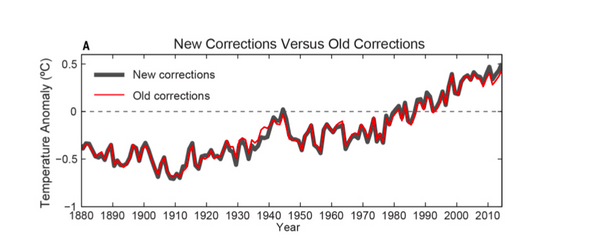

From Karl et al, 2015.

The first thing to know about the new study authored by NOAA scientists about the global warming “slowdown” or “hiatus” over the past decade is that the new analysis gets pretty deep into the details and will mainly be of interest to specialists who study climate science. In fact, for most casual readers, it doesn’t affect the overall story much at all and shouldn’t change what you think about global warming.

As I see it, interest in climate science is a bit like interest in cars. The vast majority of people couldn’t care less about the details of how their car works. They don’t know the difference between a caliper and a camshaft, and they don’t really care to know. They just want the car to run smoothly. Then there is that small but enthusiastic minority — the aficionados and grease monkeys — who not only can name every part of their engine, but who also want to be able to take it apart and fix it without the help of a mechanic. This latest study is really for the grease monkeys of climate science, the folks who know the difference between GISTEMP, HadCRUT4, and can tell you what ERSST stands for without googling it.

For the casual readers among you, here is the extent of what you’ll probably want to know about the study: the NOAA scientists who assess global temperatures have updated their analysis so that it now includes some new data that they think offers a slight improvement. The key thing to understand — for casual readers and data geeks alike — is that the changes are quite subtle. Don’t believe me? Just look at the figure at the top of this page, which shows how the old version of the NOAA analysis compares to the new one. Their newly corrected global temperature trend is the black line. The earlier version of the trend is the red line.

If you look closely, you will see the changes make the temperatures appear slightly warmer in the last decade, and thus make the idea that there has been a slowdown or “hiatus” in warming less credible. Still, that graph also makes it abundantly clear that the changes are quite minor when you look at the bigger picture. As Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, put it in a post on the Real Climate blog: “The ‘selling point’ of the paper is that with the updates to data and corrections, the trend over the recent decade or so is now significantly positive. This is true, but in many ways irrelevant.” As he has pointed out many times (as has this blog), it’s the long term trend that matters more than a handful of years here or there.

Still, there is plenty to dig into about the study for climate data geeks. The NOAA team makes the case that they’ve improved their analysis by making some updates to both the sea surface temperature and land surface temperature datasets that are at the core of the analysis. Specifically, they have included the data from the International Surface Temperature Initiative database, which more than doubles the number of weather stations available for the analysis. They have also updated the sea surface temperature by turning to a new version of the Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature dataset, which does a better job of correcting for differences in temperature measurements collected by floating buoys versus ships. Buoys are known for getting slightly cooler — and more accurate — readings than ships, but ships were the main way data was collected prior to the 1970s. The NOAA team also took a fresh look at how ship-based measurements taken with wooden buckets as opposed to engine intake thermometers compare, and how the differences might affect the overall analysis.

Not enough detail for you? If you want even more info about the study and want to know how the NOAA team came to its conclusion that there has not been a slowdown in warming over the last decade or so, you will find links to a few places where you can start your reading below the chart.

+ The full study as published in Science:

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/early/2015/06/03/science.aaa5632.full

+ Commentary by Gavin Schmidt:

http://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2015/06/noaa-temperature-record-updates-and-the-hiatus/

+ NOAA Press Release about the study:

http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/news/recent-global-surface-warming-hiatus

+ Doug McNeall (of the UK Met Office) commentary about the study:

https://dougmcneall.wordpress.com/2015/06/04/on-the-existence-of-the-hiatus

+Victor Venema (University of Bonn) commentary:

http://variable-variability.blogspot.com/2015/06/NOAA-uncertainty-monster-karl-et-al-2015.html

+ Nature news article about the study:

http://www.nature.com/news/climate-change-hiatus-disappears-with-new-data-1.17700

+Peter Thorne (International Surface Temperature Initiative) commentary:

http://surfacetemperatures.blogspot.de/2015/06/the-karl-et-al-science-paper-and-isti.html

+ Jay Lawrlmore (NOAA) commentary about the study

http://theconversation.com/improved-data-set-shows-no-global-warming-hiatus-42807

+ Washington Post article about the study:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/energy-environment/wp/2015/06/04/federal-scientists-say-there-never-was-any-global-warming-slowdown/

Every month on Earth Matters, we offer a puzzling satellite image. The May 2015 puzzler is above. Your challenge is to use the comments section to tell us what part of the world we are looking at, when the image was acquired, what the image shows, and why the scene is interesting.

How to answer. Your answer can be a few words or several paragraphs. (Try to keep it shorter than 200 words). You might simply tell us what part of the world an image shows. Or you can dig deeper and explain what satellite and instrument produced the image, what spectral bands were used to create it, or what is compelling about some obscure speck in the far corner of an image. If you think something is interesting or noteworthy, tell us about it.

The prize. We can’t offer prize money, but, we can promise you credit and glory (well, maybe just credit). Roughly one week after a puzzler image appears on this blog, we will post an annotated and captioned version as our Image of the Day. In the credits, we’ll acknowledge the person who was first to correctly ID the image. We’ll also recognize people who offer the most interesting tidbits of information about the geological, meteorological, or human processes that have played a role in molding the landscape. Please include your preferred name or alias with your comment. If you work for or attend an institution that you want us to recognize, please mention that as well.

Recent winners. If you’ve won the puzzler in the last few months or work in geospatial imaging, please sit on your hands for at least a day to give others a chance to play.

Releasing Comments. Savvy readers have solved some of our puzzlers after only a few minutes or hours. To give more people a chance to play, we may wait between 24-48 hours before posting the answers we receive in the comment thread.

Good luck!

Congratulations to reader Suzi for being the first to answer our April puzzler. As Suzi noted, the image shows South Korea’s Sisan Island. While Suzi (and several other readers) thought the offshore grid pattern was evidence of oyster or fish farming, our research suggests it is mainly seaweed farming. Several sources cited the western part of South Korea’s south coast as the main area of seaweed production, and aerial imagery of seaweed farms match the general appearance of our satellite image.

However, Suzi’s comment did prompt me to look more closely at the distribution of oyster farms and other types of aquaculture in South Korea, and it does seem possible that some of the patterns in the puzzler could be evidence of oyster aquaculture. Are there aquaculture experts or South Koreans reading this who are willing to share their opinion? Is this all seaweed or a mixture of seaweed and other types of aquaculture?

I suspect it may not be possible distinguish between seaweed farming and other types of aquaculture at Landsat’s resolution, but I would love to see somebody with more expertise prove me wrong. In the meantime, you can read what we published about this area as our Image of the Day on April 25, 2015.

Columbia University climate scientist Kátia Fernandes appeared on the cover of the 2014 Climate Models wall calendar. The calendar, dreamed up by two science writers at Columbia University, offered a fresh look on the meaning of the term ‘climate model.” Read more about the calendar from AGU’s Plainspoken Scientist blog. Image credit: Charlie Naebeck.

Based on email and social media comments we receive, climate models are one of the least understood and most maligned tools used by Earth scientists.

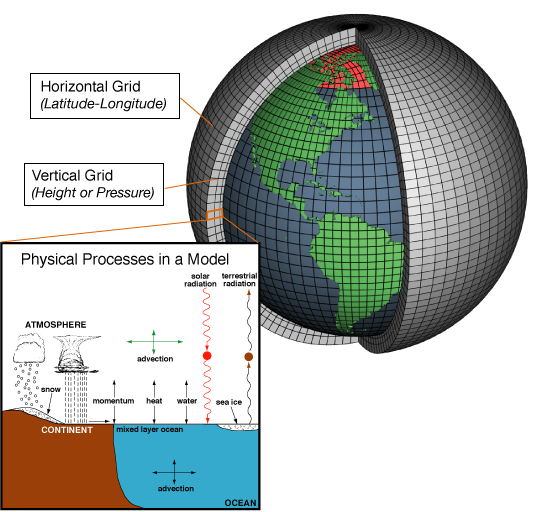

What is a climate model? Putting aside the scientists from the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory who posed for a climate model calendar in 2014 (cover above), climate models are simply mathematical representations of Earth’s climate that are based on fundamental physical, biological, and chemical laws and theories. As NOAA explained in a story about the first general circulation model to include both the ocean and atmosphere, scientists divide the planet into a three-dimensional grid, use computers to solve the equations, and then evaluate the results when they “run” a climate model. As the story noted: “Models calculate winds, heat transfer, radiation, relative humidity, and surface hydrology within each grid and evaluate interactions with neighboring points.” The illustration below should help you visualize how the grids are laid out and some of the physical processes models include.

Image credit: NOAA

One of the first general circulation models was developed at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory by Cecil “Chuck” Leith in the early 1960s. Unlike the NOAA model mentioned above, Leith’s model only simulated the atmosphere. What make Leith’s work so remarkable was that he was the first to produce a computer animation based on the model output. Watch the video below to see how these wobbling yet compelling animations looked.

From the very beginning, Leith’s animations attracted attention. “The one that I have is essentially a polar projection of the Northern Hemisphere, and you can see the patterns moving in mid-latitudes,” Leith explained during an oral history interview conducted by the American Institute of Physics. “I did it just because I knew we could do it, it would be interesting to look at, but it was almost too interesting. Whenever I’d go anywhere and give a talk about what I was doing, I would show the film and everybody was fascinated by the film, and they didn’t care what I said about the technical aspects of the model, as far as I could tell. And, in fact, Smagorinsky (another pioneer of climate modeling and the first director of NOAA) used to chide me about it a little bit. He says: ‘That’s just big plan showmanship. There’s no science there.’ But they started making movies too.” You can read more about Leith’s animation from Climate Central.

If the animation makes you curious about the history of climate modeling, try this chapter of Spencer Weart’s excellent book “The Discovery of Global Warming,” as well as this excerpt from Warren Washington’s autobiography “Odyssey in Climate Modeling, Global Warming, and Advising Five Presidents.” And if you’re looking for a more current take on climate models, how they work, and how they can be useful, see Motherboard’s new story and video profile (below) of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS). Finally, the TED talk by GISS Director Gavin Schmidt about models and the emergent patterns of climate change is well worth the twelve minutes.

The following is a statement from NASA Administrator Charles Bolden on the House of Representatives’ NASA authorization bill:

“The NASA authorization bill making its way through the House of Representatives guts our Earth science program and threatens to set back generations worth of progress in better understanding our changing climate, and our ability to prepare for and respond to earthquakes, droughts, and storm events.

NASA leads the world in the exploration of and study of planets, and none is more important than the one on which we live.

In addition, the bill underfunds the critical space technologies that the nation will need to lead in space, including on our journey to Mars.”

Several readers have asked us to post satellite imagery related to the earthquake that struck Nepal on April 25, 2015. While we regularly post imagery of natural hazards, the weather and the satellites haven’t cooperated in this case.

Some people assume NASA’s satellite fleet can collect images of virtually any part of the world in near-real time, but the reality is more complicated. The orbital track of the satellites and the specific capabilities of the sensors on board determine whether we have imagery to share. In the case of Nepal, things haven’t lined up in our favor.

NASA did acquire imagery of Nepal soon after the earthquake. The Aqua and Terra satellites capture images of Nepal every day with their identical Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) sensors. Note, however, the words “moderate resolution” in the name. Each MODIS pixel corresponds to 250 meters of the Earth — not 1 meter or less like you will find if you zoom all the way in on Google maps. MODIS does a fantastic job of showing a broad area, but if you compare an April 22 MODIS view of Nepal with an April 27 view, you’ll see the sensor doesn’t have enough spatial resolution to see changes caused by the earthquake. What’s more, it has been rather cloudy since the earthquake anyway.

Mount Everest before and after the earthquake. Not much change is visible because of a fresh coat of snow and cloud cover. The April 23 image was acquired by the Operational Land Imager on Landsat 8. The April 28 image was acquired by the Advanced Land Imager on Earth Observing-1.

Other sensors like the Advanced Land Imager (ALI) on Earth Observing-1, the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8, and the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) on Terra have much higher spatial resolution (10, 15, and 15 meters per pixel respectively…good enough to see individual buildings). But each satellite passes over Nepal much less frequently. OLI, for instance, captured imagery of Nepal on April 23, but it isn’t due for another pass until May 9. ALI did get an image of Mount Everest on April 28, but as shown in the images above, there’s no noticeable sign of the earthquake and avalanche due to a fresh coating of snow and some cloud cover. ASTER also was clouded out.

It’s also possible for the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the Suomi NPP satellite to detect the widespread blackouts that have occurred since the earthquake but, again, the weather has not cooperated. As you can see in the images (below) tweeted by NASA researcher Miquel Roman, clouds blocked the satellite’s view on April 25 (below), 26, and 27.

Why doesn’t NASA have sensors with extremely high spatial resolution (less than one meter per pixel) that like some commercial satellite companies do? (Some of those satellites have glimpsed damage to individual structures and shown groups of people congregating in streets.) That’s a complicated subject that would need a much longer blog post to explore properly, but the short answer is that NASA’s emphasis is on the broad view—using medium- and low-resolution imagers to understand macro scale processes on Earth.

NASA sensors are sometimes useful for disaster response and often provide a unique and memorable view of an event like a landslide or wildfire. Yet the strength of satellites like Terra, Aqua, Aura, Landsat, CALIPSO, Cloudsat, GPM, OCO-2, Aquarius, and GRACE is that they drive cutting-edge science by providing global perspective. Want a global map of the world’s fires? Or global view of sea surface temperatures? A map of ground water? A record of how Arctic ice has changed over decades? A view through a smoke plume as it drifts from Asia to North America? A three-dimensional perspective on the world’s forests? That’s where the NASA satellite fleet shines. For high-resolution imagery of specific events…well, there are plenty of other organizations that specialize in that.