NASA Earth Observatory map by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and calculations from Lynch, H. J., & Schwaller, M. R.

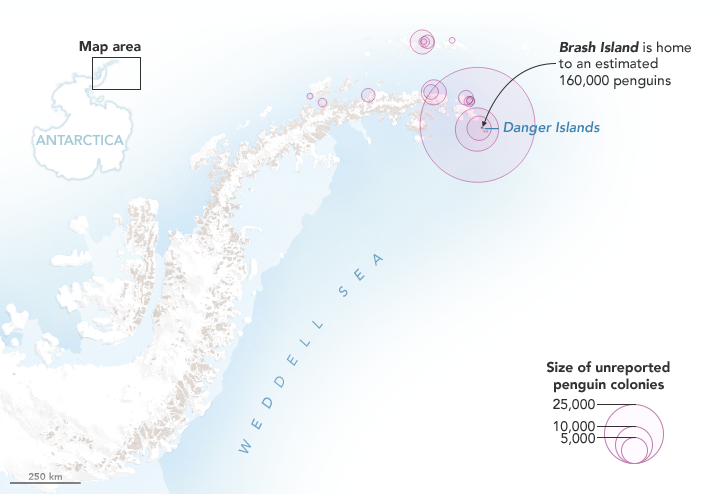

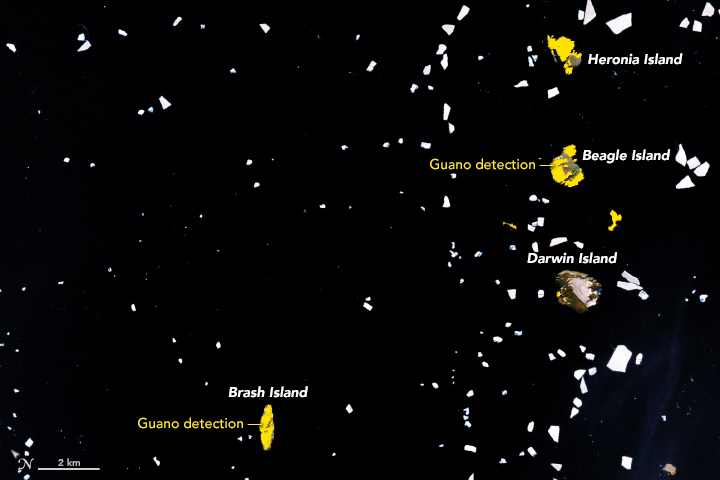

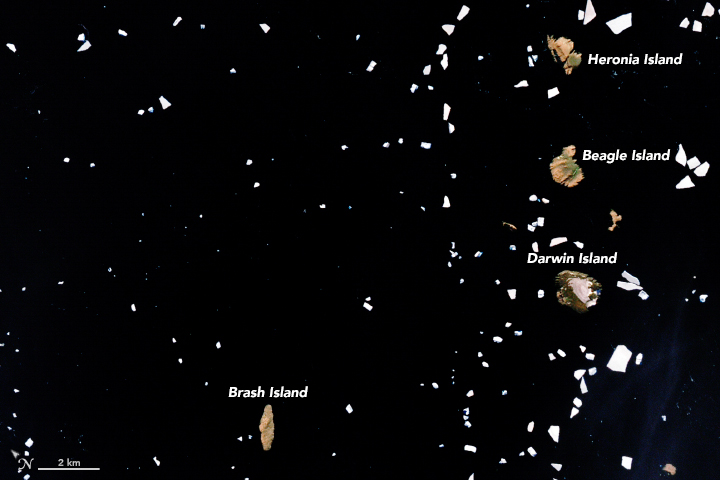

Last year, we published a story explaining how scientists had used satellite images of rocks stained pink with guano to discover several unexpectedly large colonies of Adélie penguins on the Danger Islands. Now the researchers are back with a new announcement: Using Landsat data, they have analyzed how the size of that penguin population has changed since 1982. They also used Landsat’s deep archive of satellite imagery to analyze what the penguins eat and whether their diets have changed over the past three decades.

“While the Adélie population [on the Danger Islands] is massive, it was even larger in the past,” said Heather Lynch of Stony Brook University. “We believe the population peaked in the late 1990s and has been on a slow steady decline ever since.” The scientists are still working out what may have caused the 10 to 15 percent decline in the population, but they think it is probably related to changing environmental conditions.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and calculations from Lynch, H. J., & Schwaller, M. R. (2014).

Adélie penguins are particularly sensitive to changes in climate because they require ice-free land areas to breed and access to open water. They also need enough sea ice to support populations of key food sources. The researchers thought that changing diets would accompany the decline in population, but by analyzing the spectral signatures of all the guano stains found in cloud-free Landsat image of the islands since 1982, they were surprised to discover the penguins’ diets have stayed the same.

Penguin guano ranges from white to pink to dark red. White guano is from eating mostly fish; pink and red is from mostly eating krill. The University of Connecticut’s Casey Youngflesh, however, noticed some intriguing regional patterns in what Adélie penguins eat. Colonies in West Antarctica tend to eat more krill, while colonies in East Antarctic consume more fish. The reasons for the difference are not clear, though Youngflesh is looking into the possibility that differences in the Antarctic silverfish population may be a factor.

Discovering the big colonies on the Danger Islands has also opened up a new pathway for figuring out when penguins first arrived. By digging through layers of guano-stained pebbles during a recent field expedition and dirt and dating them with radiocarbon techniques, Michael Polito of Louisiana State University worked out that penguins must have arrived on the Danger Islands about 2,900 years ago, thousands of years earlier than previous evidence suggested.

Credits: Heather Lynch, Stony Brook University.

Expect to hear even more guano-stained discoveries in the future. “We are only just scratching the surface of what we can do in terms of tracking seabirds from space,” said Lynch. “We should be able to extend the technique to snow petrel, boobies, and cormorants.”

Lynch put the total number of penguins on the Danger Islands at roughly 1.5 million (individual birds) — more than live on all the rest of the Antarctic Peninsula combined.

Read more about the Danger Island Adélie penguins from NASA and MAPPPD.

Tags: Antarctica, guano, penguins