With thousands of homes threatened by intense wildfires burning in southern California, NASA Earth Observatory checked in with Jet Propulsion Laboratory scientist Natasha Stavros to learn more about the destructive blazes.

Earth Observatory (EO): Why have these fires been so fast-moving and destructive? Are fierce Santa Ana winds the key factor? Are anomalous temperatures, rainfall, ENSO conditions, bark beetle activity, or other factors playing an important role?

There are absolutely other factors. Santa Ana winds definitely played a role in spreading the fires, but the late fire season is a more complex story. Last year, we had a lot of heavy rains, and this increased fuel connectivity by enabling grasses and annual shrubs to flourish (hence the green hills last spring). However, we had a lot of record-breaking heat waves this year.

In fact, a recent study we conducted with NASA DEVELOP and the National Park Service in the Santa Monica Mountains showed that the number of days over 95 degrees Fahrenheit stressed established vegetation and contributed to massive die-off. Even though the drought is over, the trees are still recovering from the stress of reduced water availability for such an extended period. They are in a fragile state and their defenses are down. This means that they are even more susceptible to infestation, mortality, and ultimately fire danger.

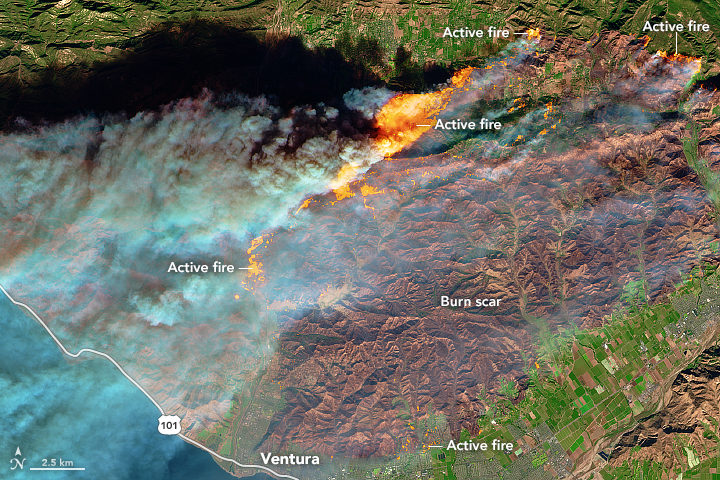

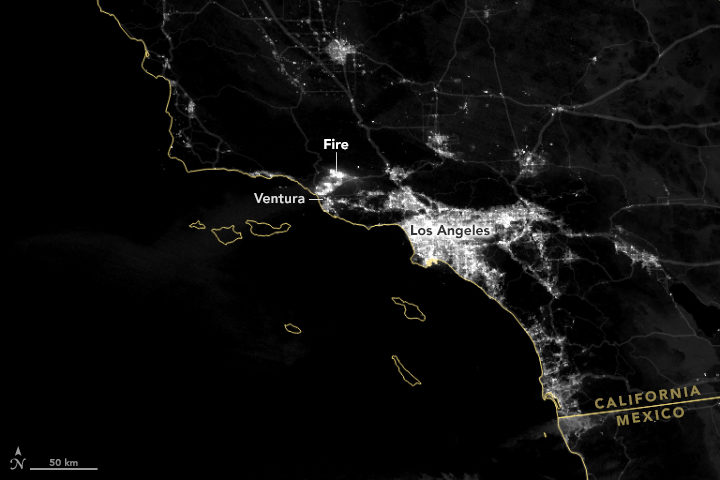

EO: We have published MODIS (top of the page), Sentinel-2 (below), and nighttime VIIRS (bottom of the page) satellite imagery of these fires. Is there anything that you find particularly interesting or notable about these images?

To me, the noteworthy thing is that the plume is going over the ocean and not the continental United States (as we saw earlier this year). This has to do with the Santa Ana winds coming from the desert and pushing particulates, ozone, carbon monoxide, and other toxic pollutants away from where people live.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2017) processed by the European Space Agency.

As for the Sentinel-2 image, this is a great shot in that it really shows the value of remote sensing in monitoring fire. Flames that look like that are tens of meters tall. The flame length is proportional to the heat released from the flame, so these fires are very hot. Just like you would not want to stand too close to a bonfire with flames tens of meters tall, fire management does not want to put personnel in the path of those flames.

Images like these and fire behavior models help inform how we think the fire will move across the landscape. There is still a lot we do not know; our models are based on what we do know, so as fires become more intense, the models do not work as well, so this is an area of active research.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens using VIIRS day-night band data from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership.

EO: Is there anything to say about how these fires fit into longer term trends and/or changing climate patterns?

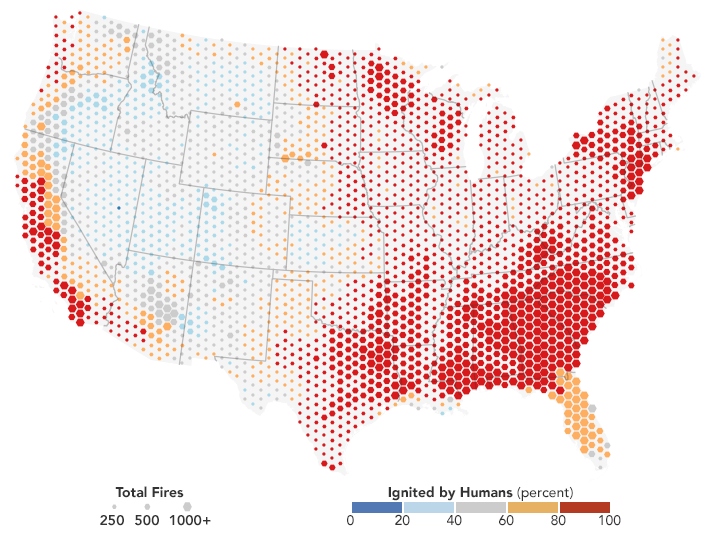

Fire regimes are changing. There is no question about that, and there are a lot of things contributing to it: climate change, a century of fire exclusion, and a growing wildland urban interface (WUI). As we move into the future, we expect there to be an increase in very large fire events. Also, and this is relevant for the events happening now, there will be longer fire seasons. Also, note that many of the fires that ignite close to where people live are actually caused by people. This is particularly true in Southern California.

As we move forward, we need to think about how to support smart fire management practices. By that I mean: what can we proactively do to reduce fire risk (i.e. the threat to valuable resources)?

Most fires on the coasts are lit by people. NASA Earth Observatory map by Joshua Stevens, using fire data courtesy of Balch, J. et al. (2017).

EO: What about JPL’s response to these fires? I was intrigued by the megafire project described here. Will your group be responding to this fire in any way?

We just received approval from NASA Headquarters to fly the Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer (AVIRIS) over these fires. This sensor has been useful for investigating fuel load type and subsequent effects on emission types, fire behavior, and post-fire analysis (e.g., safety, erosion, area burned, fire severity or the amount of environmental change caused the fire, etc.) and is often analyzed in interagency and federal-academic coordination to improve our understanding of fire.

Another effort to support fire management includes work being done from JPL in coordination with the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) to help them develop metrics of fire danger using NASA satellites that provide hydrologic variables (e.g., soil moisture and vapor pressure deficit—the difference between the amount of moisture in the air vs how much it can hold). These metrics have a one-month forecast to help allocate fire management resources nationally, which is particularly important as our fire seasons extend throughout the year in multiple places at the same time.

Natasha Stavros. Image courtesy of N. Stavros.

In 2016, we published space-based imagery of Iguazú Falls—South America’s famous system of waterfalls, which is near a bend in the Iguazú River between Argentina and Brazil. Spray from the falls reaches so high that it is visible from space. A crew member aboard the International Space Station captured the photograph above on May 24, 2016.

The view from the ground is also quite compelling, attracting more than a million visitors per year. The images below show ground-based views of the falls, photographed photographed by NASA’s Alexey Chibisov from the Argentine side of the river on November 28, 2017. Chibisov took the photos while on vacation after weeks in the field with the Operation IceBridge mission.

Photo by Alexey Chibisov.

Lush, subtropical rainforest surrounds the falls. The vegetation here is part of a remaining fragment of the Atlantic Forest, which stretches from the east coast of South America inland toward the Amazon. The forest is habitat for tens of thousands of plant species and thousands of animal species.

Photo by Alexey Chibisov.

Sediment carried by the fast-moving river can impart a red-brown color to the water, especially after periods of heavy rain.

Photo by Alexey Chibisov.

The mist is the result of water that plunges as much as 260 feet (80 meters) over layers of basalt cliffs.

Every month on Earth Matters, we offer a puzzling satellite image. The November 2017 puzzler is above. Your challenge is to use the comments section to tell us what we are looking at, when the image was acquired, and why the scene is interesting.

How to answer. You can use a few words or several paragraphs. You might simply tell us the location. Or you can dig deeper and explain what satellite and instrument produced the image, what spectral bands were used to create it, or what is compelling about some obscure feature in the image. If you think something is interesting or noteworthy, tell us about it.

The prize. We can’t offer prize money or a trip to Mars, but we can promise you credit and glory. Well, maybe just credit. Roughly one week after a puzzler image appears on this blog, we will post an annotated and captioned version as our Image of the Day. After we post the answer, we will acknowledge the first person to correctly identify the image at the bottom of this blog post. We also may recognize readers who offer the most interesting tidbits of information about the geological, meteorological, or human processes that have shaped the landscape. Please include your preferred name or alias with your comment. If you work for or attend an institution that you would like to recognize, please mention that as well.

Recent winners. If you’ve won the puzzler in the past few months or if you work in geospatial imaging, please hold your answer for at least a day to give less experienced readers a chance to play.

Releasing Comments. Savvy readers have solved some puzzlers after a few minutes. To give more people a chance to play, we may wait between 24 to 48 hours before posting comments.

Good luck!

In this satellite image, the prominent Pinacate Peaks stick out above the sand dune landscape of the Gran Desierto de Altar in Mexico’s Sonoran Province. The peaks are located just south of the Mexico-United States border. The Gran Desierto de Altar is one section of the broader Soronan Desert which covers much of northwestern Mexico and reaches into Arizona and California.

Steady, consistent winds in the area have shifted low-lying sand into dune fields in intriguing regular patterns. These same patterns of sand dune fields appear around the world in desert areas.

The volcanic peaks and cinder cones are believed to have formed from volcanic activity that first started roughly 4 million years ago — most likely due to the plate tectonics that also formed the Gulf of California around the same time. The most recent activity was perhaps 11,000 years ago. During the late 1960s, NASA trained astronauts in field geology at a number of sites around the world, including Pinacate Peaks, as preparation for the lunar landings.

The natural color image here is from the Landsat 8 satellite using its Operational Line Imager (OLI) instrument. The image was acquired on October 3, 2017. The volcanic cinder cone field stains the landscape of bright sand and tall dunes in the El Pinacate y Gran Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve.

NOTE: In a previous version of this post, I featured the EO-1 ALI image below, and an astute reader pointed out that these peaks, while in the Biosphere Reserve, are not Pinacate Peaks, but rather the Sierra de Rosario range nearby. I am geographically and tectonically embarassed…

The natural color image here is from the now-defunct Earth Observing 1 (EO-1) satellite using its Advanced Land Imager (ALI). The image was acquired on December 16, 2012. This late-year scene was just days before the solstice (the farthest south the Sun appears in the sky), so the tallest sand dunes and the volcanic peaks cast unusually long shadows across the ground.

EO-1 was launched in November 2000 as an engineering testbed for new sensor technology; in particular, the ALI instrument was a predecessor for the Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager. The EO-1 mission was so successful that it was extended past its original 18-month mission, and was only recently retired after 17 years of operation.

This post is republished from the Landsat science team page.

In the giddy, early days following the flawless launch of Landsat 8, as the satellite commissioning was taking place, the calibration team noticed something strange. Light and dark stripes were showing up in images acquired by the satellite’s Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS).

Comparing coincident data collected by Landsat 8 and Landsat 7 — acquired as Landsat 8 flew under Landsat 7, on its way to its final orbit — showed that thermal data collected by Landsat 8 was off by several degrees.

This was a big deal. The TIRS sensor had been added to the Landsat 8 payload specifically because it had been deemed essential to a number of applications, especially water management in the U.S’s arid western states.

The TIRS error source was a mystery. The prelaunch TIRS testing in the lab had shown highly accurate data (to within 1 degree K); and on-orbit internal calibration measurements (measurements taken of an onboard light source with a known temperature) were just as good as they had been in the lab. But when TIRS radiance measurements were compared to ground-based measurements, errors were undeniably present. Everywhere TIRS was reporting temperatures that were warmer than they should have been, with the error at its worst in regions with extreme temperatures like Antarctica.

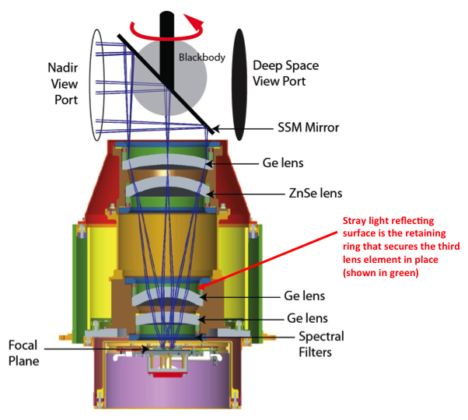

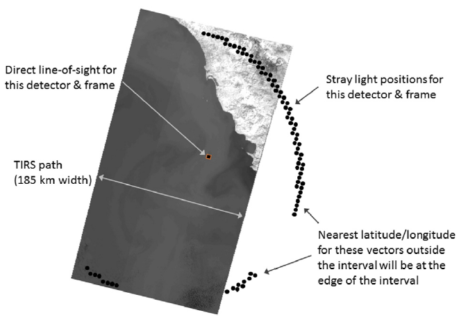

After a year-long investigation, the TIRS team found the problem. Stray light from outside the TIRS field-of-view was contaminating the image. The stray light was adding signal to the TIRS images that should not have been there—a “ghost signal” had been found.

Scans of the Moon, together with ray tracing models created with a spare telescope by the TIRS instrument team, identified the stray light culprit. A metal alloy retaining ring mounted just above the third lens of the four-lens refractive TIRS telescope was bouncing out-of-field reflections onto the TIRS focal plane. The ghost-maker had been found.

With the source of the TIRS ghosts discovered, Matthew Montanaro and Aaron Gerace, two thermal imaging experts from the Rochester Institute of Technology, were tasked with getting rid of them.

Montanaro and Gerace had to first figure out how much energy or “noise” the ghost signals were adding to the TIRS measurements. To do this, a stray light optical model was created using reverse ray traces for each TIRS detector. This essentially gave Montanaro and Gerace a “map” of ghost signals. Because TIRS has 1,920 detectors, each in a slightly different position, it wasn’t just one ghost signal they had to deal with— it was a gaggle of ghost signals.

To calculate the ghost signal contamination for each detector, they compared TIRS radiance data to a known “correct” top-of-atmosphere radiance value (specifically, MODIS radiance measurements made during the Landsat 8 / Terra underflight period in March 2013).

Comparing the MODIS and TIRS measurements showed how much energy the ghost signal was adding to the TIRS radiance measurements. These actual ghost signal values were then compared to the model-based ghost signal values that Montanaro and Gerace had calculated using their stray light maps and out-of-field radiance values from TIRS interval data (data collected just above and below a given scene along the Landsat 8 orbital track).

Using the relationships established by these comparisons, Montanaro and Gerace came up with generic equations that could be used to calculate the ghost signal for each TIRS detector.

Once the ghost signal value is calculated for each pixel, that value can be subtracted from the measured radiance to get a stray-light corrected radiance, i.e. an accurate radiance. This algorithm has become known as the “TIRS-on-TIRS” correction. After performing this correction, the absolute error can be reduced from roughly 9 K to 1 K and the image banding, that visible vestige of the ghost signal, largely disappears.

“The stray light issue is very complex and it took years of investigation to determine a suitable solution,” Montanaro said.

This work paid off. Their correction—hailed as “innovative” by the Landsat 8 Project Scientist, Jim Irons—has withstood the scrutiny of the Landsat Science Team. And Montanaro and Gerace’s “exorcism” has now placed the Landsat 8 thermal bands in-line with the accuracy of the previous (ghost-free) Landsat thermal instruments.

USGS EROS has now implemented the software fix developed by these “Landsat Ghostbusters” as part of the Landsat Collection 1 data product. Savvy programmers at USGS, led by Tim Beckmann, made it possible to turn the complex de-ghosting calculations into a computationally reasonable fix that can be done for the 700+ scenes collected by Landsat 8 each day.

“EROS was able to streamline the process so that although there are many calculations, the overall additional processing time is negligible for each Landsat scene,” Montanaro explained.

Gerace is now determining if an atmospheric correction based on measurements made by the two TIRS bands, a technique known as a split window atmospheric correction, can be developed with the corrected TIRS data.

Meanwhile, Montanaro has been asked to support the instrument team building the Thermal Infrared Sensor 2 that will fly on Landsat 9. A hardware fix for TIRS-2 is planned. Baffles will be placed within the telescope to block the stray light that haunted the Landsat 8 TIRS.

The Landsat future is looking ghost-free.

Related Reading:

+ RIT University News

+ TIRS Stray Light Correction Implemented in Collection 1 Processing, USGS Landsat Headline

+ Landsat Level-1 Collection 1 Processing, USGS Landsat Update Vol. 11 Issue 1 2017

+ Landsat Data Users Handbook, Appendix A – Known Issues

References:

Montanaro, M., Gerace, A., Lunsford, A., & Reuter, D. (2014). Stray light artifacts in imagery from the Landsat 8 Thermal Infrared Sensor. Remote Sensing, 6(11), 10435-10456. doi:10.3390/rs61110435

Montanaro, M., Gerace, A., & Rohrbach, S. (2015). Toward an operational stray light correction for the Landsat 8 Thermal Infrared Sensor. Applied Optics, 54(13), 3963-3978. doi: 10.1364/AO.54.003963 (https://www.osapublishing.org/ao/abstract.cfm?uri=ao-54-13-3963)

Barsi JA, Schott JR, Hook SJ, Raqueno NG, Markham BL, Radocinski RG. (2014) Landsat-8 Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) Vicarious Radiometric Calibration. Remote Sensing, 6(11), 11607-11626.

Montanaro, M., Levy, R., & Markham, B. (2014). On-orbit radiometric performance of the Landsat 8 Thermal Infrared Sensor. Remote Sensing, 6(12), 11753-11769. doi: 10.3390/rs61211753

Gerace, A., & Montanaro, M. (2017). Derivation and validation of the stray light correction algorithm for the Thermal Infrared Sensor onboard Landsat 8. Remote Sensing of Environment, 191, 246-257. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2017.01.029

Gerace, A. D., Montanaro, M., Connal, R. (2017). Leveraging intercalibration techniques to support stray-light removal from Landsat 8 Thermal Infrared Sensor data. Journal of Applied Remote Sensing, Accepted for Publication.

Every month on Earth Matters, we offer a puzzling satellite image. The October 2017 puzzler is above. Your challenge is to use the comments section to tell us what we are looking at, when the image was acquired, and why the scene is interesting.

How to answer. Your answer can be a few words or several paragraphs. (Try to keep it shorter than 200 words). You might simply tell us what part of the world an image shows. Or you can dig deeper and explain what satellite and instrument produced the image, what spectral bands were used to create it, or what is compelling about some obscure speck in the far corner of an image. If you think something is interesting or noteworthy, tell us about it.

The prize. We can’t offer prize money or a trip to Mars, but we can promise you credit and glory. Well, maybe just credit. Roughly one week after a puzzler image appears on this blog, we will post an annotated and captioned version as our Image of the Day. After we post the answer, we will acknowledge the person who was first to correctly ID the image at the bottom of this blog post. We may also recognize certain readers who offer the most interesting tidbits of information about the geological, meteorological, or human processes that have played a role in molding the landscape. Please include your preferred name or alias with your comment. If you work for or attend an institution that you want us to recognize, please mention that as well.

Recent winners. If you’ve won the puzzler in the last few months or work in geospatial imaging, please sit on your hands for at least a day to give others a chance to play.

Releasing Comments. Savvy readers have solved some of our puzzlers after only a few minutes or hours. To give more people a chance to play, we may wait between 24-48 hours before posting the answers we receive in the comment thread.

Good luck!

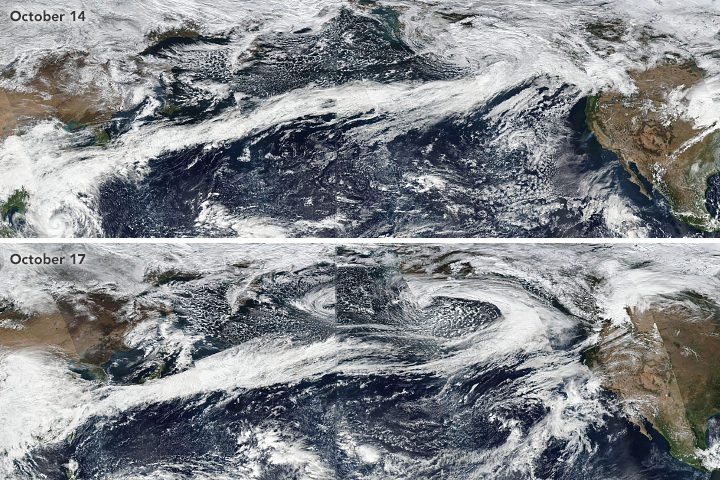

Atmospheric rivers stretched from Asia to North America in October 2017. Learn more.

If you live on the West Coast of North America, you have probably heard meteorologists talk about “atmospheric rivers” — the narrow, low-level plumes of moisture that often accompany extratropical storms and transport large volumes of water vapor across long distances. When atmospheric rivers encounter land, they can drop tremendous amounts of rain and snow. That can be good for replenishing reservoirs and for quenching droughts, but these remarkable meteorological features can also trigger destructive floods, landslides, and wind storms.

During the past decade, atmospheric rivers have fueled a flood of another type: scientific research papers. Prior to 2004, fewer than 10 studies mentioned atmospheric rivers in any given year; in 2015, about 200 studies were published on the matter. The availability of increasingly sophisticated satellite and aircraft data has fueled the trend, according to a recent article in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Here’s a sampling of what scientists have learned about these rivers in the sky.

They Can Bring Rains, Winds, And Lots of Damage

In a study led by Duane Waliser of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and published in Nature Geoscience, researchers showed that atmospheric rivers are among the most damaging storm types in the middle latitudes. Of the wettest and windiest storms (those ranked in the top 2 percent), atmospheric rivers were associated with nearly half of them. Waliser and colleagues found that atmospheric rivers were associated with a doubling of wind speed compared to all storm conditions.

They Shift With The Seasons

During the winter, atmospheric rivers in the Pacific generally shift northward and westward, Bryan Mundhenk of Colorado State University and colleagues concluded in a study. They also found that the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle can affect the frequency of atmospheric river events and shift where they occur. The research was based on data processed by MERRA, a NASA reanalysis of meteorological data from satellites.

They Aren’t Just a West Coast Thing

Atmospheric rivers are a global phenomenon and responsible for about 22 percent of all water runoff. One recent study from a University of Georgia team underscored that the U.S. Southeast sees a steady stream of atmospheric rivers. “They are more common than we thought in the Southeast, and it is important to properly understand their contributions to rainfall given our dependence on agriculture and the hazards excessive rainfall can pose,” said Marshall Shepherd of the University of Georgia. Other studies note that atmospheric rivers have contributed to anomalous snow accumulation in East Antarctica and extreme rainfall in the Bay of Bengal.

Climate Change Could Alter Them

A recent study led by Christine Shields of the National Center for Atmospheric Research suggests that climate change could push atmospheric rivers in the Pacific toward the equator and bring more intense rains to southern California. The modeling calls for smaller increases in rain rates in the Pacific Northwest. Another ensemble of models shows a in the number of days with landfalling atmospheric rivers in western North America.

Satellites Are Key to Studying Their Precipitation

While there are few ground-based weather stations in the open ocean to tally how much rain falls, satellites such as those included in the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission can estimate precipitation rates from above. “Satellites have proven valuable over both the ocean and land, though uncertainties are often larger over land because of complicating factors like the terrain and the presence of snow on the surface,” said Ali Behrangi, the author of a study that assessed the skill of different satellite-derived measurements of precipitation rates.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Jesse Allen, using VIIRS data from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership.

You have probably heard or read that it has been rather smoky out West this year. Dozens of large wildfires have raged through forests in British Columbia, Alberta, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, California, and other states this fire season. Intense blazes are lofting up so much smoke that huge plumes have been blowing across the country—and even turning up in Europe. We checked with a few scientists who specialize in studying wildfires for an update on what is going on.

EO: How does this fire season compare to past years?

The western fire season has been quite active this year. British Columbia has surpassed its greatest burned area in the modern era. While its unlikely that this season will be record-breaking in the western U.S., it is above normal relative to the past decade, which has seen abundant fire activity.

— John Abatzoglou, University of Idaho

EO: Is climate change exacerbating these fires?

Because we have let fuels build up in the western U.S., it is difficult to tell in many ecosystems what is weather-driven vs. climate-driven until we get back to normal fuel loads. This 2013 PNAS paper tries to answer the climate question given the artificially increased fuel loadings. They found that climate change is responsible for 55 percent of the observed increasing fuel aridity. — Jessica McCarty, Miami University

EO: Are bark beetles making these fires worse?

No, the bark beetle outbreaks have little-to-no relationship with trends in area burned or the ecological severity of fires. I think this continues to be a big misconception with the public, which is understandable because climate is a key driver of both bark beetle outbreaks and wildfires. Many people jump to the conclusion that bark beetle outbreaks are causing fires. But it is likely a classic case of correlation without causation. — Brian Harvey, University of Washington

EO: If there was one thing you wished Americans understood about wildfires in the West, what would it be?

Be careful with fire. Smokey the Bear is trying to educate you on the risk—listen. Heed fire risk and fire weather warnings. Don’t build campfires unless you have to. Don’t go off-roading during droughts and heat waves. Be careful with your cigarette butts. — Jessica McCarty, Miami University

Even though no one is a fan of widespread smoke, wildfires aren’t inherently “bad” [when they are in unpopulated areas]. One continuing challenge is figuring out how to live with fire as part of the system as more people settle in the region during an era of changing environmental conditions. — John Abatzoglou, University of Idaho

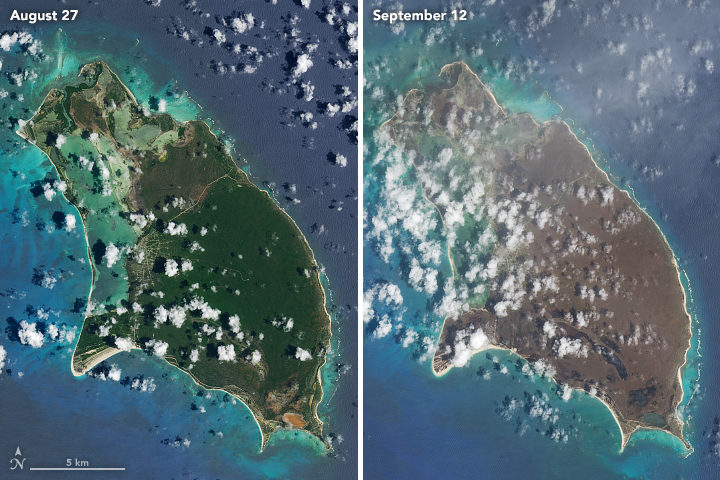

NASA Earth Observatory images of Barbuda by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

We recently posted several striking pairs of satellite images of Caribbean islands before and after they were hit by Hurricane Irma. The images show lush, green vegetation turning a dark shade of brown. We were curious about what exactly caused the damage and how quickly vegetation might recover, so we checked in with Edmund Tanner, a University of Cambridge ecologist who has authored multiple studies about vegetation damage and recovery after Caribbean hurricanes.

EO: What were the primary mechanisms that turned the islands brown? Leaves blown away by the wind? Mud and debris covering them up? Salt spray killing them off?

Away from the sea (100 meters or so), most of the green to brown is the loss of green leaves because they were blown off. Native vegetation on these islands has been through hundreds of hurricanes since the last major change of climate (10,000 years ago, the end of the most recent ice age) and have been naturally selected to lose leaves and small branches and re-sprout. I doubt if it is mud since the fairly heavy rain will have washed that off. Most of the water falling on the vegetation would have be fresh—rain—not sea spray.

EO: How long will it take for the vegetation to recover?

My guess is the greening up in the lowlands will take 6 months, with a lot happening in the first 3-4 months. You can probably measure that from satellite images. On the ground, there will be lots of sprouts on tree trunks. For larger trees, the surviving branches will produce leaves and small branches and slowly these will shade out and kill the epicormic shoots produced on the lower parts of trunks

.

EO: What about storm surge? Was that a major factor in killing trees and other vegetation?

Salt water from storm surge may have killed trees whose roots were inundated with it. Those trees will take much longer to recover because the soil will need to be desalinated naturally by rain, and seeds will have to germinate and grow. The areas involved are not likely to be large—a fringing zone of a few hundred hectares in some places.

EO: How useful are satellites in assessing vegetation damage caused by hurricanes?

Very useful. Especially for measuring the change in green from before the hurricane to brown immediately after the hurricane, to greening up over weeks and months after the hurricane. Modern analyses of satellite images could also show the decrease in individual tree canopy size if trees lost big branches and only regrew them slowly.

Every month on Earth Matters, we offer a puzzling satellite image. The August 2017 puzzler is above. Your challenge is to use the comments section to tell us what we are looking at, when the image was acquired, and why the scene is interesting.

How to answer. Your answer can be a few words or several paragraphs. (Try to keep it shorter than 200 words). You might simply tell us what part of the world an image shows. Or you can dig deeper and explain what satellite and instrument produced the image, what spectral bands were used to create it, or what is compelling about some obscure speck in the far corner of an image. If you think something is interesting or noteworthy, tell us about it.

The prize. We can’t offer prize money or a trip to Mars, but we can promise you credit and glory. Well, maybe just credit. Roughly one week after a puzzler image appears on this blog, we will post an annotated and captioned version as our Image of the Day. After we post the answer, we will acknowledge the person who was first to correctly ID the image at the bottom of this blog post. We may also recognize certain readers who offer the most interesting tidbits of information about the geological, meteorological, or human processes that have played a role in molding the landscape. Please include your preferred name or alias with your comment. If you work for or attend an institution that you want us to recognize, please mention that as well.

Recent winners. If you’ve won the puzzler in the last few months or work in geospatial imaging, please sit on your hands for at least a day to give others a chance to play.

Releasing Comments. Savvy readers have solved some of our puzzlers after only a few minutes or hours. To give more people a chance to play, we may wait between 24-48 hours before posting the answers we receive in the comment thread.

Good luck!

Answer: The image above shows the burn scar left by a palm swamp fire in Brazil along the Peruaçu River. Rather than producing big, orange flames and billowing plumes of smoke, this fire smoldered underground in dried out, carbon-rich soil and likely peat. The fire spread slowly through soil and roots, but it was able to move up the hollow trunks of palm trees in the area and burn off the canopy. Nobody guessed the location, but congratulations to Monica Craig and Lee Hurst for guessing that it was related to a fire. Read more about the image in our September 5, 2017, Image of the Day.