Three thick layers of cake and frosting sat atop Jeff Schmaltz’s kitchen counter. The programmer had completed a 3-D model of a GIBS tile pyramid; it was his entry into a collegial science bake-off at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. But there was more to this cake than flour and eggs and sugar.

This tile pyramid cake shows a view of the world with Antarctica represented as the largest continent on the map. Credit: Susan Schmaltz.

If you have ever browsed Earth science imagery and data using the online tool Worldview, then you have also used GIBS, Global Imagery Browse Services. GIBS is like a gear behind a clock face, a mechanism that keeps the hands moving. Schmaltz and his colleagues rely on it daily as they assemble images of our dynamic planet. (Worldview is a free and publicly available Earth science browser used by scientists and non-scientists, including the NASA Earth Observatory team.)

How It Works

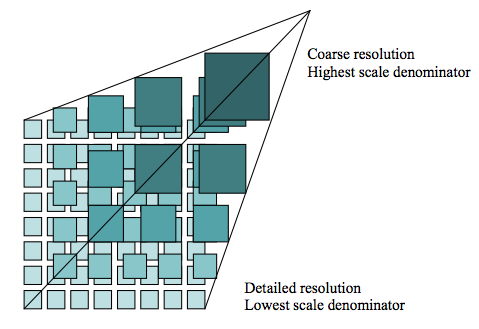

GIBS ingests and organizes satellite data to create a global mosaic. Then, it chops down the data into digestible bits—like that image tile pyramid that Schmaltz recreated with cake—so that users can quickly view Earth as seen from space.

Zoomed out in a broad view, you see just the top tile, the whole Earth in low resolution (like the top layer of the cake). Zoomed in, you see one tile covering a smaller region of the earth but in more detail (like a square from the bottom layer of the cake). On an interface like Worldview, which allows users to scroll and view daily images from the entire surface of Earth, an architecture like GIBS is necessary to keep the site running quickly.

“It’s very fast, and there’s not a lot of computing going on,” Schmaltz said. GIBS does the same thing that Google Maps does: it summons only the data the user requests. By dealing in tiles, the program can serve many people at once without getting bogged down.

GIBS uses tiles (512 x 512 pixels) to speed up data processing. Credit: The Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC).

Way Back When

Not long after NASA launched the Terra satellite in late 1999, the U.S. experienced a record fire season: A record 8.4 million acres burned in the year 2000. At the time, it could take weeks for data from Terra’s MODIS instrument to be processed into images. Scientists hoped that a quicker turnaround might translate into a more informed response to fires. As result, NASA created a near-real time fire pixel product.

Seventeen years later, scientists can visit Worldview to see roughly 150 near-real time data sets from different satellites and sensors as the clouds and snow cover change each day. Air pollution, vegetation cover, dust, smoke are just a few of the data layers users can view.

Credit: NASA.

P.S. To make Jeff’s satellite cake, follow his grandmother’s recipe below:

Ingredients:

Directions:

Mix dry ingredients together. Measure oil, water, egg yolks, and vanilla into a measuring cup and mix; then add to dry ingredients and beat until smooth.

Beat 2 egg whites + ¼ tsp. cream of tartar until stiff. Fold into batter. Slowly mix in grated chocolate.

Bake in ungreased 8×8 pan at 350 degrees for 20-25 minutes. Check with toothpick when done. Cool on a rack. Goes best with chocolate frosting. (Schmaltz uses the recipe on the side of a Hershey’s can.) Alternately, you can top the cake with an edible print of a satellite image.

Credit: Adam Voiland.

The past few weeks have been rough on Earth-observing satellites. (The past decade hasn’t been great either.) But there was some good news and some engineering prowess to go along with the troubles.

On April 8, 2012, the European Space Agency’s Envisat suffered a permanent loss of communications for reasons that engineers have been unable to figure out so far. The failure came just a few weeks after the satellite celebrated its 10th anniversary.

The Thematic Mapper — the primary natural-color imager on America’s venerable Landsat 5 satellite — officially ended regular operations on May 8, following several months of operator attempts to revive it. TM collected images for 27 years, and several hundred of them are part of our Earth Observatory archives. Landsat controllers are happy, however, to be collecting data once again from the Multispectral Scanner (MSS) on Landsat 5, an instrument that had not worked for nearly a decade. The next generation of Landsat is scheduled for launch in 2013.

NASA’s Earth Observer 1 (EO-1) satellite also broke off regular operations and went into a “safe mode” in April. But in that case, there is happier news.

EO-1 halted operations after experiencing a low battery charge. Like almost all satellites in earth orbit, EO-1 uses solar panels to generate electricity for its systems and to charge its batteries for orbits on the night side of Earth. Think of it like a mobile telephone that runs until the battery is low and then needs to be recharged. Except EO-1 gets drained and recharged and drained 14 times a day. Every day for the past decade.

The satellite also gets bombarded by space radiation, particularly while passing through the South Atlantic Anomaly, where electrically charged particles trapped by the Earth’s magnetic field graze deeper into the atmosphere than in other spots. The satellite also endures cycles of heating in direct sunlight and freezing in the shade…over and over again.

Low-Earth orbiting satellites like EO-1 are built to endure these cycles of charge and discharge, hot and cold, light and dark, radiation bombardment and calm vacuums. But it’s always a little amazing to think about how many variables those satellites are designed to survive.

After a few weeks of sleepless nights and long days, the NASA team was able to coax EO-1 back into operations by resetting everything on the satellite and reloading all of the flight and operations software. Think of it like reseting your computer by unplugging it and turning it back on. Granted, it’s a lot more complicated, and mission engineers had to be very sure they understood why the problem happened so it didn’t happen again right after the reset.

EO-1 has been back in operations for several weeks since its two week spring break. The “first/return to light” image above shows Christchurch, New Zealand, as viewed by the Advanced Land Imager (which was actually designed to test technologies for the next generation of Landsats). The satellite appears to be back in good health, but you can read more about the anomaly on the EO-1 satellite page. (Look for the document “EO-1 Safehold Anomaly 2012:097:23:59 2012:111:23:59” near the bottom of the page. If that seems cryptic, it’s an indication of the time of the anomaly: just shy of midnight on day 97 of 2012 (April 6) to day 111 (April 20)).