On April 15, 1999, Landsat 7 first made its way into space. 106,380 orbits later, the 2.6 million images acquired by Landsat 7 have given us a fuller and more nuanced understanding of Earth.

Take for example the Millennium Coral Reef Mapping Project. In 2006, Landsat 7 data were used to create a first-of-its kind global survey of coral reefs. The research lead on this project, Frank Muller-Karger, commented in 2015: “Until we made the map of coral reefs with Landsat 7, global maps of reefs had not improved a lot since the amazing maps that Darwin drafted.”

Landsat 7 data, together with data from its predecessor Landsat 5, provided the most comprehensive assessment ever of Earth’s mangroves in 2010.

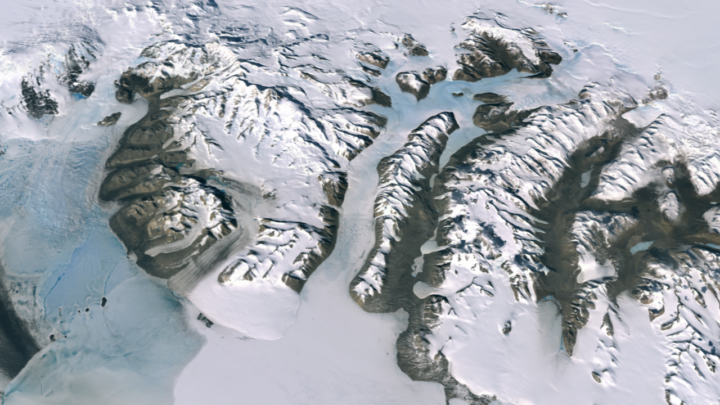

And for the International Polar Year (2007-2008), data from more than 1,000 Landsat 7 images were used to create the Landsat Image Mosaic of Antarctica (LIMA)—what was then the most detailed satellite mosaic of Antarctica.

If we travel two decades back in time and rewind the 4,733,375,587.686 kilometers that Landsat 7 has flown since April 1999, we arrive at a very different moment in spaced-based Earth observation.

The commercially-owned Landsat 6 satellite had failed to reach orbit six years earlier. Landsat 5 was 12 years past its design life and operated by a for-profit entity that charged upwards of $4000 per image and collected international data only when there was an immediate customer. Both situations curtailed the systematic global coverage of Earth that had been envisioned by the Landsat Program’s founders.

A building consensus about the critical role of Earth observation data for global change research had led the National Space Council to recommend that Landsat 7 be built. It should be operated by the U.S. government to ensure a continuous global archive of medium-resolution data for the long-term monitoring of Earth’s land surface. This was codified with the 1992 U.S. Land Remote Sensing Policy Act.

When Landsat 7 launched on April 15, 1999, the Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) instrument onboard was the most sophisticated Landsat sensor yet. ETM+ carried a new 15-meter panchromatic band and had a thermal band with a spatial resolution refined to 60 meters (compared to 120 meters for Landsat 4 and 5). It also carried a new solid-state data recorder—one of the first to fly on a civilian mission. For the first time in Landsat program history, Landsat 7 was equipped with hardware that could reliably store large amounts of imaged data onboard for later download when a ground station was in range.

Landsat 7’s state-of-the-art recorder, together with a strategic global image acquisition plan, enabled the best global coverage the program had ever known. The LIMA project lead, Robert Bindschadler, penned in a 2001 journal article that “The revolutionary concept of systematic collection of Landsat 7 data timed to optimize anticipated scientific applications will make possible a global monitoring of the cryosphere with a data set heretofore only available in limited regions.”

During its ascent into orbit in 1999, Landsat 7 collected data as it flew under Landsat 5. This enabled the cross-calibration of Landsats 5 and 7. (In 2013, Landsat 8 underflew Landsat 7 for the same reason). Additionally, a team of calibration scientists oversaw in-the-field calibration efforts, making certain that satellite measurements agree with physical ground measurements. Such careful data calibration ensures that the Landsat data record can show meaningful trends of land use and land cover change—even when the changes are subtle.

In May 2003, an image scanning mechanism on Landsat 7 (the Scan Line Corrector) failed, leaving wedge-shaped gaps in the imagery—a net loss of 22 percent of each image. As devastating as this failure was, the remaining data are, as USGS describes, “some of the most geometrically and radiometrically accurate of all civilian satellite data in the world.”

The landmark 2008 USGS decision to make all Landsat data free and open, and the subsequent trend towards best-pixel composite-based data analysis, has made these data gaps even less problematic.

All in all, Landsat 7 has made remarkable contributions to global studies for two decades now, and according to fuel-based predictions, it should be able to continue doing so until the launch of Landsat 9.

Did you know?

In the second it took you to read this line, Landsat 7 traveled about 7.499 kilometers.

The launch of Landsat 7 was the second image ever posted on NASA Earth Observatory.

The Landsat 7 Mission Operations Control Center is staffed by 14 engineers, seven days a week, 8 hours a day. Someone is always on call and ready to respond if a ground or spacecraft anomaly occurs.

References:

Goward, S.N. et al. (2017) Landsat’s Enduring Legacy: Pioneering Global Land Observations from Space. Bethesda, MD: American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing.

Wulder, M.A. et al. (2019) “Current status of Landsat program, science, and applications.” Remote Sensing of Environment 225:127-147.