By Clément Miège

It might be hard to believe but yes, we are still in town! We have been delayed for a full week now, every day getting ready for a possible flight the next day, and every morning, we get the same message: “Unfortunately, there will be no flight to the ice cap today due to weather and bad visibility with low clouds, but tomorrow looks more promising.” Oh, no! Even if it is fully justified, it is always a bit disappointing the moment you hear that, but I think our team has a good experience already with this kind of delay and we are able to switch quite easily and still be happy and optimistic for a flight the next day.

The main helping factor that puts us back in a good mood comes from the weather forecast. Indeed, every day we are able to see a clear-sky window that makes us think that we will be able to fly the next day. Sometimes, this weather window can be very tiny, but it is always there! Good spirits!

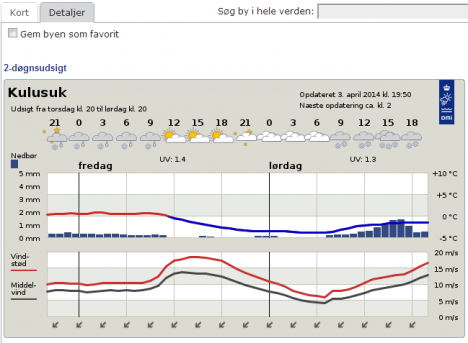

Tomorrow, again, it looks great, with a weather window in the afternoon (Forecast provided by the Danish Meteorological Institute .)

When you look at long-trend forecasts (beyond the following 48 hours), the weather is changing a lot in short spans of time. Often, there are significant changes from one forecast to its updated version a couple of hours later. For example, a 5-day storm, with heavy precipitation, appears in the forecast, but then it it is removed from the next update. So our moods shift quite a bit. For even longer trends, it becomes a different story. Rick shared with Ludo and me his experience with the so-called “Canadian Forecast”. It consists of making the last 5-6 days of a 14-day weather forecast always be nice and sunny, to keep people happy through the winter so they can anticipate the end of it. We can verify this “happy weather trend” in Greenland with our own Danish Forecast — the five last days of this forecast are always sunny. We are keeping a record of the forecast since we arrived two weeks ago, and we can say this is a regular pattern.

After checking weather forecast here, our daily duties are not done yet! Next, we take a look at the data from a weather station that is currently in the field, in our future camp site. We dropped the weather station as part of our cargo last week, but we did not have time to set it up. It is however transmitting data and our IMAU colleagues gave us access to the transmitted data. Unfortunately, the signal for diurnal temperature is getting weak, it’s almost nonexistent anymore, which means that the weather station is getting buried. More and more snow will need to be removed to access our equipment when we will get to camp (maybe tomorrow?) Next, we take a look at the Kulusuk airport’s flight schedule for the day. We can see for example that the Tiniteqilaaq flight is canceled (“aflyst”, in Danish) and that the Isortoq flight is delayed. Then, we do the same thing for the Tasiilaq heliport schedule and then we speculate (while drinking our coffee) where our flight fits in this schedule. We are getting quite good at this exercise! Our flight never fits and we are always rescheduled. But there are some events that are still out of our control. Three days ago, a domestic conflict in Kuummiut required the police Marshall to solve it. Since the Marshall is based in Tasiilaq, the helicopter had to fly him there. That day we had woken up at 5:30 am for a flight scheduled to leave at 7:05, which got rescheduled to 11 am, and after three additional hours waiting at the airport, it eventually became a cancelled flight. Needless to say, the helicopter never made it to the Kulusuk airport. We simply went back to the hotel in the pouring rain. As Ludo likes to say: “This is again craptastic; good times!”

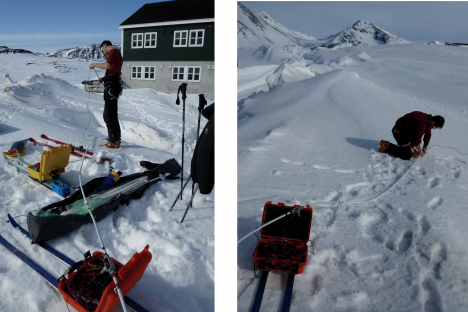

Sunday (March 30) was a beautiful day though, but we were not on the flight schedule — the pilots had to catch up with the Saturday flights had been cancelled. We took advantage of the nice weather to further test our field equipment. As I mentioned in an earlier post we will be testing a low-frequency radar system in the aquifer region on the ice sheet. Laurent Mingo at Blue System, who develops the IceRadar is letting us test a beta version of one of his radar systems. The IceRadar is currently used by many research groups on alpine glaciers, ice caps and ice islands. As such, it has been deployed in many regions of the world (Yukon, Rocky Mountains, Himalaya, Bhutan, Iceland, the Andes, the European Alps…) to perform ice thickness measurements and bed mapping, but also to look at the glacier englacial properties. I believe this is the first trip for the IceRadar to the Greenland ice sheet. So we are quite honored to have this system with us to try it over the aquifer.

Setting up the IceRadar for the first time in Greenland, with the 5 MHz antennas. The lower the frequency used for the radar, the longer the antenna has to be. For a 5MHz system, the antenna length is 20 meters (about 70 feet), and there are two of them (receiving and transmitting). (Credit: Rick Foster)

After the setup, we try our radar going from the seasonal snowpack to the relatively thin sea ice – that gives us important changes in terms of dielectric constant, which look quite obvious in the radar profile. The system total length is about 50 meters (164 feet), so no sharp turns are allowed! (Photo credit: Rick Foster.)

Getting the 40MHz IceRadar ready, you can see the difference of the antenna size — this is definitely easier to turn. (Photo credit: Rick Foster)

Rick watches Ludo and me maneuvering the IceRadar from the hotel. A new (feline) friend is also observing us, probably wondering what we are doing here! (Credit: Rick Foster.)

At the end of the day we have great news: the IceRadar is working well at the two frequencies tested, which is really promising toward our ice sheet measurements. YAY!

Finally, the hotel still does not have running water. As Ludo mentioned in an earlier blog post, the heating element in the water pipe supply line that prevents the water from freezing broke. And the road to get to the lake with fresh water is still being plowed, but the bad weather and drifting snow prevent the plow truck from making much progress. We are getting used to showering with a water bucket and becoming more and more efficient at conserving water.

Without water at the hotel, we are even more motivated for going to the ice sheet since we know we will not be missing a good hot shower anyway.

Our team has a really good feeling for tomorrow, so let’s hope for a “go” and keep our fingers crossed!

Cheers, Clément on the behalf of the aquifer team.

Tags: Arctic, climate change, cryosphere, drilling, Greenland, NASA, polar