So, I realize that it’s been awhile, and that in my last blog post (from waaaaaaaaaaaaaay back in January of 2020) I said that we’d be doing a launch from New Zealand but that didn’t quite work out nearly as well as we all hoped… I wonder what happened…

Anywho, your ever-faithful intrepid engineer is back in the saddle again here in Fort Sumner, New Mexico, for our fall campaign attempt. We did do a spring Fort Sumner campaign earlier in the year, but that is pretty rare for the Balloon Program. Normally, during that time of year, we are attempting to conduct launches from either Wanaka, New Zealand, or the Swedish Space Corporation Esrange facility outside Kiruna, Sweden. Next year in March through June the blogs might be a little more exotic. Why didn’t I put up any blog posts back in the spring? Well, I was busy … and stuff. We had a lot to do to make both the spring and fall campaigns for this year happen. Now, where was I?

What’s been happening in Fort Sumner, you ask? Good question! We’ve been deployed here to the Land of Enchantment since early August. We currently have nine manifested missions slated for the fall campaign. We’re attempting to launch some science piggyback missions on a couple of Columbia Scientific Balloon Facility test flight missions. We also have a full slate of dedicated science missions we want to launch. AND we have an independent student mission. I’ll be sure to give more info on that one in a later post.

So far, the team has conducted one hand-launch for the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) science mission WHATSUP. Now, I’ve talked about hand launches in previous blog posts (“More Fun Than a BARREL of Electrons” primarily), but what makes this mission special is that the Principal Investigator, Adrian Tang, is developing a system to go to other planets and measure water content in their atmospheres. That’ll help us understand the composition of gases that make up the “air” on said planets in our solar system. You can see some shots of the WHATSUP mission in the above pictures. The image below is from the launch last week.

Today, we just launched another NASA JPL mission. The JPL-SLS. The balloon, as I’m writing, is at 28,680 feet and climbing. She’s currently climbing at a little less than 1000 feet per minute. You can check out the current conditions (more likely the final trajectory) here. The JPL-SLS mission is an upper atmosphere science mission for NASA that is looking at and measuring the composition of our own atmosphere. We’ve flown JPL-SLS many times in the past, so they’re able to use their data to measure trends and see how our atmosphere has changed over time.

The opening video is from our launch attempt today (August 28, 2021). That is the JPL-SLS mission being released from the launch spool and the mobile launch vehicle. The last photo for today was taken of the JPL-SLS mission from the flight line. I hope you enjoy! I’ll try to do better to keep this updated with more observations from the field. Check back real soon!

We’ve wrapped up operations for launching balloons from McMurdo for this year and I wanted to give a final update about what we’ve been up to on the ice. Since our last launch, we’ve been moving people off continent and sending them home and have started to focus on our upcoming campaign from Wanaka, New Zealand. But that isn’t the end our job here in Antarctica. And yes, I finally saw some penguins for the animal lovers out there, hence my opening video.

This year we launched three balloons from our camp. Two of them have already been brought down so we could begin to recover the high value instrument components, the science data hard drives, and our command and control systems for the balloons. The third balloon (above), the pathfinder mission I talked about in “More Fun Than a BARREL of Electrons,” is expected to fly for 100 days, and, as I write this, we’re still only at day 24. So that flight has a long way to go before it’s brought down. For the other two flights, the National Science Foundation (NSF) supports out scientists and recovery personnel with dedicated flights to where the instruments landed after their missions. The conditions on the ground are always different and requires people to puzzle out how to dismantle the instruments and their gondolas to fit in the aircraft at our disposal.

The more capable of the type available to us is the Basler, which is modified Douglas DC-3. The Basler is able to carry more weight, has a bigger door, and can fly further. But the Basler also needs a better runway to take off and land from, so that usually means sending out equipment to groom a runway on the ice before it can head out. That usually falls to a Twin Otter to prep the recovery site and begin operations for bringing the instruments home. The Twin Otter was originally designed by de Havilland Canada. The Twin Otter is a lighter, easier to land aircraft that is used quite frequently in Antarctica.

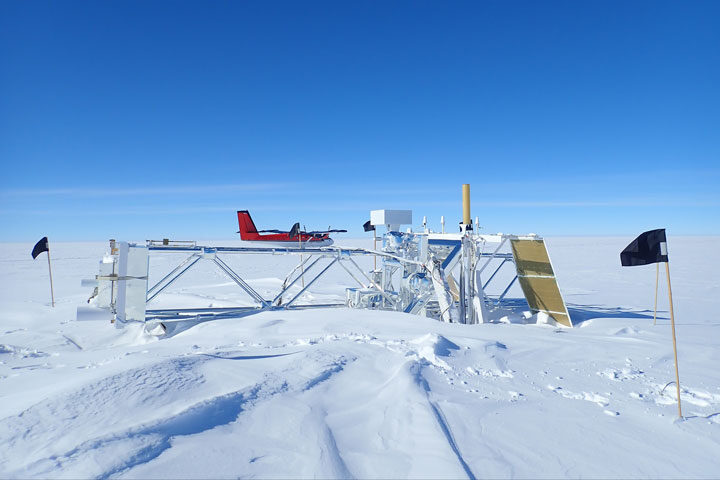

As I mentioned before, once the recovery teams get on site, they start dismantling the payloads so they can be removed from the ice in compliance with the Antarctic Conservation Act. What this means for us is that if we brought it on continent, then we need to take it off continent. And where some of our flights end up, this process can take years. We’re still recovering a science instrument from a flight that we launched last year. The X-Calibur mission recovery team actually had to be stationed at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. Here’s a photo of X-Calibur after it was left last year for us to recover this year.

After all the recovery operations are as complete as possible for this year, that’s when we bring the last of our people home and NSF winterizes our buildings so they are protected from the long winter ahead. As the saying goes: “All good things must come to an end.” But the Balloon Program will be back again next year to continue launching balloons from this unique place and help make amazing discoveries that can only be done there. As always, thanks for checking out my blog and be on the lookout for information about our next campaign from New Zealand.

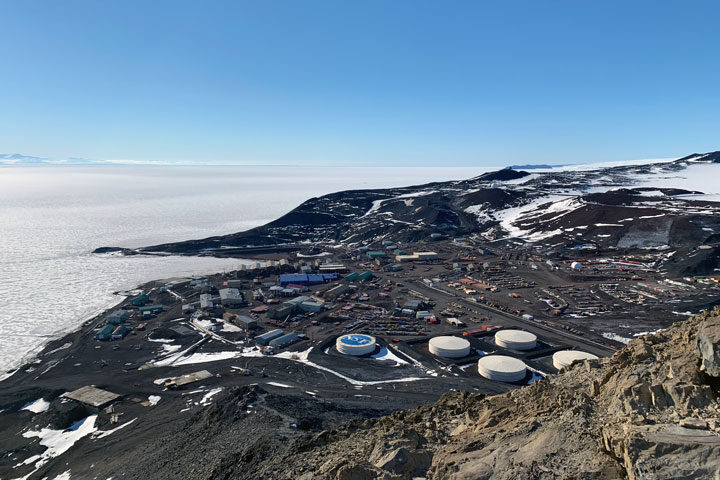

This blog post is going to be a little different than my previous ones, so bear with me as I tread on new ground. I wanted to cover a little of what life is like down here in McMurdo Station while we’re launching our balloons for the Long Duration Balloon campaign here on the Ross Ice Shelf. My opening photo for today was taken from the top of Observation Hill, which is a 750-foot summit that overlooks McMurdo Station, and it took me about 45 minutes to climb one way, so enjoy! Now back to ballooning…

When we launch from most other locations around the globe, we have pretty set times for conducting our launches. In Fort Sumner, New Mexico we pretty much show up at about 3 a.m. for all attempts. With the very rare exception, we might have a night launch opportunity, but those are few and far between. In Palestine, Texas, where the Columbia Scientific Balloon Facility is located, we launch balloons in the late afternoon which gives us pretty consistent night flight opportunities. All of this is really dependent on the prevailing winds at that time of the season. Esrange in Kiruna, Sweden and Wanaka, New Zealand (Spoiler: this is where the next series of blogs are going to come from!) aren’t quite as predictable, but are usually around the same time of day.

But here in Antarctica, the winds and weather are not nearly that predictable. So far this campaign, we’ve shown up at our camp for multiple launch attempts at 11 a.m. in the morning, 7 p.m. in the evening, and most recently we’ve been leaving at about 1-3 a.m. If this schedule sounds a little rough, well, that is because it is. I’ve already talked a little bit about SuperTIGER’s delay that was four hours, so even when trying to predict a start time that doesn’t mean the weather is going to cooperate.

As far as getting around, this place is like an off road testing facility of continental sized proportions! I’m not going to be able cover every type of vehicle that is roaming around down here, but I CAN show you some of my favorites! Since Christmas, we’ve essentially been working straight nights to conduct our launch attempts. Mostly, we’ve left McMurdo Station in a couple of off-road vans and a Delta shown above. As you can see in the picture, it’s a really big off road vehicle. Most of them down here were turned over to the National Science Foundation (NSF) when the U.S. Navy gave them the facility. So that shows that they were built to last and to take a beating.

When our schedules are a little more consistent, we get a ride from the United States Antarctic Program Shuttles Operations team for our daily commute. The Shuttle Ops team has a few different vehicles they use for our daily transport, but the most iconic is “Ivan the Terra Bus.” Ivan was also made by the same company that continues to provide the DELTAs.

And if you truly need to go where no one has gone before, you can take a Tucker Sno-Cat. I haven’t had the “pleasure” of riding around in one of these, but apparently they are a pretty rough and energetic ride. Oh, and loud. Really, really loud for the passengers. But since they are a treaded vehicle, they really don’t need roads to get where they’re going.

Like I said at the start, this isn’t my usual forte for my blogs, but the engineer in me is always fascinated by big machines that work in extreme environments. And here in Antarctica, everything has to perform or none of the amazing science that is done here would be possible. I have to also say that the support we get from NSF and their team makes all of our launches possible and we wouldn’t be able to launch our balloons without them. Thanks again for checking in and I hope you liked this glimpse into our daily lives here.

I realize that, you know, its New Year’s and all. But while everyone is waiting for that big ball to drop in Times Square, here outside McMurdo, we’ve been working to send balloons UP! We just had a super successful launch of a 0.6 million cubic foot (MCF) balloon. Now, for us at in the Balloon Program Office, that’s a pretty small balloon; we generally launch balloons that are anywhere from 4 to 39 MCF. But the 0.6 MCF platform gives us a capability to support a whole lot of scientists that have small and very sensitive instruments with the ability to go where only we can take them. Up above you can see how these small balloons look just prior to launch.

This flight really supported two missions for us. First of all, the instrument that we launched on the balloon was a part of a program ran by Dr. Robyn Millan at Dartmouth College. Robyn and her team are using the BARREL instrument to study electron losses from the Van Allen Radiation Belts. The instrument is able to capture when electrons literally fall out of the sky and measure their energy. One of the big things that their work will help everyone with is how to better protect satellites from the radiation in space.

The second thing we want from this launch is for the balloon to be a pathfinder for a future NASA Explorers Program mission. We will use the trajectory that this flight follows, a similar flight from last year, and another follow on flight scheduled for next year to help bound the expected flight path for the future GUSTO mission. GUSTO will be studying emissions from the particles that are in interstellar (between the stars) space and help shed light on the lifecycle of stars in our galaxy.

Now, I realize that 0.6 MCF is a pretty abstract number, so for those of you (like me) that think in real dimensions I wanted to give you an idea of just how “small” these balloons really are. When fully inflated, the 0.6 MCF balloon is 72.5 feet by 124.5 feet (yes, I said feet), and it quite frankly looks like a pumpkin! So if you take your average pumpkin from October and make it 55 times bigger then you have a 0.6 MCF balloon. Easy, right? Another way to visualize it is if you took three full sized school buses and put them end to end, then that’d be the diameter of this balloon. Sounds pretty small to me.

I also want to circle back to that “pumpkin” shape I mentioned earlier. Another thing that made this launch super was that this was a Super Pressure Balloon. This design of balloon actually maintains constant pressure during its entire flight (just like a party balloon), and that gives us very good altitude stability during day and night transitions and long flight durations. Our record from last year’s Antarctic campaign was 73 days.

My picture today is of the BARREL instrument at the foot of our flight line with Mt. Erebus in the background. And if you look behind BARREL, the red plastic on the ground is our balloon in its covering that protects it while we lay it out prior to launch. Thanks again for checking out my Notes from the Field: Balloons for Science blog. And most importantly, have a happy New Year!

Welcome again to below the 77th parallel. I know it’s only been a few days since my last post went live, but I have some great news from WAY down south. Today, I wanted to cover the picture-perfect launch of the SuperTIGER mission from our Long Duration Ballooning Camp from here outside McMurdo Station, Antarctica.

On the 16thof December, we left McMurdo Station at 1 p.m. to catch a ride to our camp for a 10 p.m. launch attempt. Once we got there, our Weather Wizard (most people would call him a meteorologist, but what he does seems like magic to me) told us that the time we could launch the balloon would be later than we thought. How much later you ask? Try four hours later!! So with that bit of good news, the launch crew and science team that were there to support launch did what they could to get ready and then we waited. Once we finally had a handle on how the winds were blowing, we started our launch operations. Aside from the delay, everything went as smooth as silk.

The fist picture shows the SuperTIGER instrument on our Mobile Launch Vehicle. Because we like our acronyms so much, we usually just call it the “MLV.” The first thing that is done on a launch day is we take the instrument out and put in on our launch vehicle so the science team can make some final checks of their communication systems. Down here in Antarctica, we use a lot of satellite radios for transmitting the data from the instrument back to the computers that the scientists use to do their work. All of this happens on the launch vehicle.

The second picture shows SuperTIGER, the almost quarter mile flight train, and the very top section of the balloon waaaaaaaay in the back! Between SuperTIGER and the balloon is all the equipment we need to make the mission safely fly. There is a parachute, some more communication systems, and other stuff that allows us to track the balloon and make sure that it’s flying just fine.

The last photo for today is from the actual launch right after the balloon was released from the ground. It was a bit of a cloudy day, but for us all that really matters is that the winds aren’t too strong.

I know… I know… Enough of this launch stuff, now you want to know what SuperTIGER does. Well, once again I’m just completely blown away but what our scientists can do. The SuperTIGER instrument is trying to see what kind of elements (like hydrogen, helium, iron… Stuff from the periodic table) are created when stars go supernova. SuperTIGER is primarily wanting to measure elements that are heavier than iron. The scientists that are taking these measurements are trying to understand how our own (home, sweet home) solar system was made. In the words of the principal investigator Brian Rauch: “It is true that the information we gather will help us understand how the stuff that we, our world, and indeed the rest of the visible universe are made of is created from the basic building blocks left over from the Big Bang. We are after all made of star dust, and we are measuring individual pieces of that.” That’s pretty out of this world if you ask me!