On our team’s last day at Kilbourne Hole, we were joined by retired astronaut Harrison “Jack” Schmitt, the lunar module pilot for Apollo 17. He is the only professional geologist to have walked on the Moon and is still an active researcher.

Schmitt joined our 2017 excursion for very much the same reason that Butch Wilmore came: to provide feedback about the instruments and how they could be used during an EVA. He also helped the scientists investigate the local geology of Kilbourne Hole and how this feature developed.

Apollo 17 astronaut Jack Schmitt discusses the value of training astronauts in geology and the appeal of Kilbourne Hole, in particular. NASA/GSFC

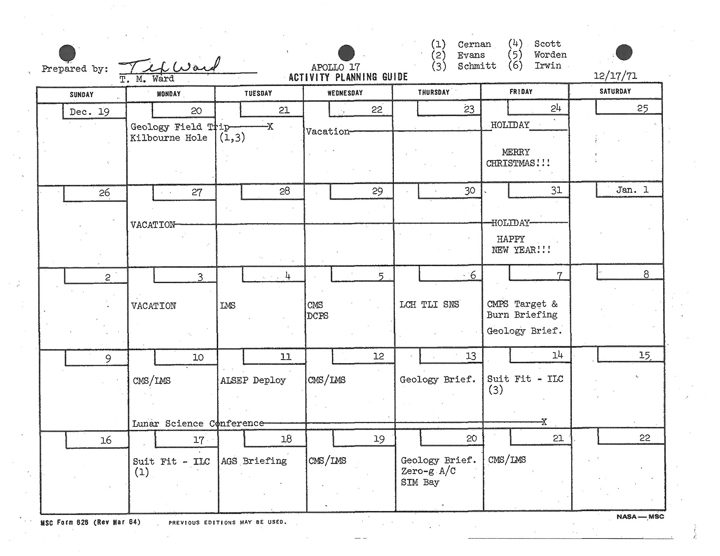

Before our trip, Schmitt’s most recent visit to Kilbourne Hole had been about 45 years earlier, when he had gone there for Apollo 17 training. Apollo astronauts underwent field training in geology at various sites representing a range of geological features. Kilbourne Hole was one. Other locations used at various times included, but were not limited to, sites in western Texas, Hawaii, Arizona, California and Canada. Because of Schmitt’s expertise in geology, he helped train other Apollo astronauts in how to identify and collect interesting samples.

Among the training activities listed for Apollo 17 astronauts is a geology field trip for Eugene Cernan and Jack Schmitt to Kilbourne Hole on December 20 and 21, 1971. NASA

At Kilbourne Hole this time, Schmitt recalled how his training there had informed his interpretations of what he was observing on the Moon.

December 2017 marks the 45th anniversary of Apollo 17. Astronaut Jack Schmitt looks back on the mission and what it was like to set foot on the Moon.

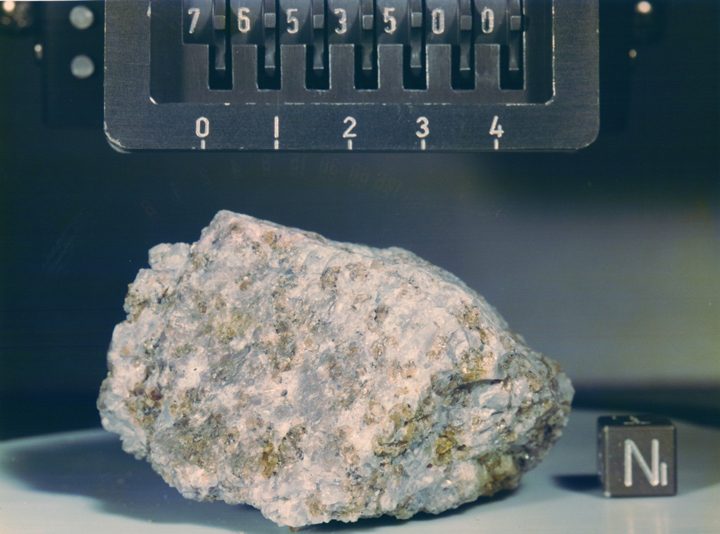

The landing site for Apollo 17 was the Taurus-Littrow valley, a geologically intriguing area selected so that astronauts could collect samples of ancient rocks from the lunar highlands and look for evidence of young volcanic activity. There, Schmitt collected the “most interesting sample returned from the Moon.” It’s a rock known as sample #76535, which was collected as part of the rake sample at Station 6, located on the North Massif. Like the xenoliths we searched for at Kilbourne Hole, sample #76535 is olivine-rich. It’s a very old specimen that had not been damaged by shock events, and its origin is still being debated.

The olivine-rich Apollo 17 sample #76535 was measured at up to 5 centimeters across with a mass of 156 grams. NASA

One aspect of our work is studying is how different types of information can be combined to help the scientists understand the site from during and after an EVA. We brought an array of instruments and cameras, which I’ll describe below. We also brought a collaborator from Canada, Ben Feist, to explore ways to combine data to make the scenery and the work easy to visualize. He has done this before with Apollo 17 data, providing an immersive, you-are-here feeling.

Our collaborator Ben Feist. Courtesy of Ben Feist.

So what did we bring? To give us the big picture, we brought two unmanned aerial vehicles, one like a robotic plane (see image below), and the other a quad-copter. Both gave us excellent 2D horizontal views, and the data can even be used to make 3D models of the terrain. Butch Wilmore and Liz Rampe also wore cameras during their simulated EVAs.

The robotic plane is ready for launch at Kilbourne Hole. Courtesy of Ben Feist.

The unmanned aerial vehicle is great for horizontal views, but it’s not as helpful for viewing vertical surfaces. For a task like mapping cliffs at Kilbourne, or lava pits at Aden Crater, we need to combine the airborne instruments with surface cameras that also provide 3D views. The instrument we brought for this purpose was a lidar, which is similar in concept to radar except that it uses laser pulses to measure distances. Mounted on a tripod, the instrument scans across a panorama and then swivels all the way back to the starting point to take a series of pictures covering the same area. After the operator sets up the sweep, everyone has to make sure they stay out of the field of view while the lidar scans, a maneuver the team calls the “lidar dance.”

The lidar on its tripod. NASA/GSFC

Team members Patrick Whelley (left) and Jacob Richardson (right) set up the tripod-mounted lidar. NASA/GSFC

The team also set up a hyperspectral camera, which shows us what the landscape looks like in the thermal infrared region of the spectrum, where heat is sensed. This camera can identify rocks and soils based on the amount of energy emitted at various infrared wavelengths. This can be helpful for prioritizing which areas to target first and for documenting a site and providing the geologic context for the samples taken.

Team member Deanne Rogers from Stony Brook University explains the use of the hyperspectral camera. NASA/GSFC

To investigate the chemistry of the rocks, we brought a handheld X-ray fluorescence instrument, or XRF, which bombards a sample with high-energy radiation to measure how much the material fluoresces. That gives us information about the composition of the sample. We also brought a handheld laser-induced breakdown spectrometer, or LIBS, which vaporizes a small sample of rock to give us information about its composition.

Team member Kelsey Young explains the use of the X-ray fluorescence spectrometer. NASA/GSFC

Team member Amy McAdam explains the use of the laser induced-breakdown spectrometer. NASA/GSFC

Traveling with us were four journalism students from the Stony Brook University School of Journalism; their professor, Elizabeth Bass, the founding director of the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University; and teaching assistant Kevin Lizarazo. This group joined us in the field to see firsthand how research gets done. They hiked into the field day after day and documented just about every aspect of the trip, from the geology of the sites and the instruments we used to the personalities of our team members—even creating a gallery of our hats. All of their work has been synthesized and distilled into a multimedia-rich Reporting RIS4E website, created by the students under the supervision of Lizarazo.

Having students report from the field has been an essential part of RIS4E since the project was launched in 2014. The project leadership worked with the Stony Brook University School of Journalism and the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science to create a course for students interested in science journalism that puts them in contact with researchers while they work. In 2015, the first group of students traveled with a RIS4E team to Hawaii’s Mount Kīlauea volcano.

The journalism students and teachers from Stony Brook University (left to right): Briana Lionetti, Kayla McKiski, Jake Bleacher, Nicola Shannon, Elizabeth Bass, Katherine Wright, and Kevin Lizarazo. Courtesy of Reporting RIS4E.

The land at Potrillo is desert, and temperatures were especially hot during our time in the field. On the first day, the thermometer registered 105 degrees Fahrenheit, making for a harsh introduction to the desert, as the Stony Brook journalists described in their “Dispatches from the Desert” blog.

The volcanic landscape is difficult terrain, and by the end of the trip, several pairs of boots had to be tossed in the trash, including these two. We can rate the field difficulty by how many pairs of boots don’t come home. Courtesy of Patrick Whelley.

The combination of explosive and effusive volcanic features creates a rugged terrain that can be difficult to walk on. For some in the group from Stony Brook, this was a new experience. I use the term “lava legs”—similar to sea legs—to refer to mastering walking on the uneven volcanic terrain. I awarded buttons to those who earned their lava legs on my trips.

Our first destination in Potrillo was Kilbourne Hole, a maar crater that was formed about 16,000 to 24,000 years ago. It’s an irregular hole measuring about 1-1/2 miles by 2 miles. Kilbourne is thought to be the result of a steam explosion that occurred when hot magma encountered shallow groundwater. The result was excavation of the crater and deposition of layered deposits that record the history of water here.

Panorama of Kilbourne Hole, with dark basalt visible in the crater walls. Courtesy of Ben Feist.

After a few days at Kilbourne Hole, we visited Aden Crater, where lava flows piled up to form a gently sloping volcano known as a low shield. As the lava continued to flow away, the summit collapsed, leaving a bowl-shaped depression called a caldera. The emplacement of lava flows at Aden led to a variety of other depressions, some of which are linked to lava tubes or underground caves, and some which are not. Understanding which pits will lead to caves is important because future explorers might use caves as shelter or as promising locations for scientific investigation. This was the main goal for our work at Aden Crater.

Team member Jose Hurtado of the University of Texas at El Paso explains how Kilbourne Hole formed and notes similarities to some features on Mars. NASA/GSFC

At Kilbourne Hole, the group looked for xenoliths, material that is brought up from deep in Earth’s mantle by volcanic activity and gets trapped inside other rocks. In this case, the xenolith is the greenish mineral olivine, which is sometimes used as a gemstone called peridot. NASA/GSFC

After a few days at Kilbourne Hole, we visited Aden Crater, where lava flows piled up to form a gently sloping volcano known as a low shield. As the lava continued to flow away, the summit collapsed, leaving a bowl-shaped depression called a caldera. The emplacement of lava flows at Aden led to a variety of other depressions, some of which are linked to lava tubes or underground caves, and some which are not. Understanding which pits will lead to caves is important because future explorers might use caves as shelter or as promising locations for scientific investigation. This was the main goal for our work at Aden Crater.

The terrain at Aden crater, a low shield volcano, is much different than Kilbourne Hole. Courtesy of Ben Feist

Team leader Jake Bleacher reviews the plan for the group’s first day at Aden crater. Courtesy of Ben Feist.

Jacob Richardson and Ben Feist check out a deep hole with cold air coming out, a welcome respite on a 104-degree day. A hot desert wind can be heard blowing. NASA/GSFC

We came to Potrillo to conduct field excursions that simulate EVAs, or extravehicular activities, which are like the moonwalks that Apollo astronauts took on the lunar surface. Future astronauts might conduct something like a moonwalk on the surface of another rocky planetary body. Our research helps answer the question: If astronauts are going to explore volcanic features on the surfaces of other planets or moons, what kinds of instruments should they bring, and how will they use the different types of data that they collect?

Astronaut Butch Wilmore and geologist Liz Rampe, both from Johnson Space Center in Houston, joined us for the EVA activities. They carried out some of the tasks that a crew might perform, and then gave us feedback about the use of instruments during EVAs. This feedback is valuable for us because it’s from the perspective of someone who has conducted spacewalks from the International Space Station (Wilmore) and of someone who has expertise as a field geologist and operating rovers on the surface of Mars (Rampe).

This information helps us build and prepare to use instruments that would be ready for spaceflight and planetary exploration. Goddard has a long history of building instruments, and we’re adding to that legacy by learning as much as we can about how well different kinds of instruments work for the tasks that explorers would have to perform on the surfaces of other planetary bodies.

NASA astronaut Butch Wilmore talks about simulated extravehicular activities that the team conducted in the Potrillo volcanic field and how the excursion sites were chosen. NASA/GSFC

Footage from the camera worn by Butch Wilmore shows Liz Rampe working with him on simulated extravehicular excursions at Kilbourne Hole. NASA/GSFC