Sea ice geophysicist Melinda Webster is blogging from the RV Polarstern, an icebreaker ship locked in Arctic sea ice for the MOSAiC expedition. Webster will use MOSAiC data as a blueprint to evaluate and extend the seasonal capability of data from NASA’s ICESat-2 satellite for sea ice research.

On August 17, the Polarstern reached the North Pole during its search for a new ice floe for the MOSAiC observatory, the research icebreaker Polarstern. We made surprisingly quick progress through the sea-ice pack owing to thin, warm ice conditions and a fragmented sea-ice cover. It took us less than seven days to cover 597 nautical miles (676 miles/1,087 kilometers) in a straight-line distance. The ice at the North Pole was level, seasonal ice extensively covered in dark melt ponds. I can only imagine how different it must have looked 30 years ago when thick, hummocky multiyear sea ice was more normal.

From the North Pole, we established a new ice camp at 87.717N, 104.313E on about 1.3-meter thick, first-year sea ice with numerous interconnected melt ponds. About half of the melt ponds were completely melted through to the ocean and the floe itself contained a network of old, melted cracks. These conditions required us to wear survival suits for much of our field work. After bouts of rain, snow, freezing, and melting, we were lucky enough to experience freeze-up, a time when the sea-ice cover begins to grow continuously from autumn to spring.

Two days ago, we completed our work at the snowy, frozen ice camp and began our journey to Bremerhaven, Germany. As we travel through the ice pack, we’re conducting “ice stations”–measurements collected at certain locations to capture the spatial variability in snow depth, melt pond depth, and sea ice thickness, which are important for understanding Arctic sea ice characteristics during the autumn transition. Yesterday, we observed snow cover that was about 8 centimeters deep, refrozen melt ponds, and “fields” of frost flowers on refrozen leads. Today, we’re traveling through wet first-year ice with open melt ponds covering about 25 percent of the area–a stark contrast from conditions yesterday due to a recent storm that passed through with above-freezing temperatures and rain.

As the Polarstern passes through changing ice conditions on our way southward, I can’t help but wonder what the sea-ice cover looked like 30 years ago and what it will look like 30 years from now.

Sea ice geophysicist Melinda Webster is blogging from the RV Polarstern, an icebreaker ship locked in Arctic sea ice for the MOSAiC expedition. Webster will use MOSAiC data as a blueprint to evaluate and extend the seasonal capability of data from NASA’s ICESat-2 satellite for sea ice research.

June 10, 2020

Our first night aboard Polarstern was a pleasant one. Even though we had 4-meter waves and 7 Beaufort force winds, we were tired and slept rather well in our new home.

At 8:15 a.m. Universal Time the next morning, the first sea ice came into view. We stood about on the helicopter pad in our bulky life jackets (during a safety drill), watching whales and bright patches of white on the horizon. Morale was high.

At 8:37 a.m. Universal Time, we officially reached the Arctic sea-ice pack. There was a surprisingly distinct boundary between the “open” ocean and pack ice. Often times in mid-summer, this boundary can be ambiguous with small floes and brash ice scattered all about, but not here. The ice floes remained together, fenced in by an invisible boundary of warm water: surface ocean temperatures were 4°C just before the ice edge and -1.8°C within.

As the ice edge approached, we began our “ice observations,” a task in which we characterize the weather and surrounding ice and open water conditions every hour, estimating sea-ice concentration, thickness, snow cover, melt ponds, cloud cover, precipitation, and more. This is valuable information for comparing with satellite products such as sea ice concentrations and the sea-ice edge maps used for navigation. Learning where products work well (and don’t work well) helps us identify areas for improvement and also informs user groups, such as a ship’s crew, about how to better use the products.

The greater vicinity of the ice pack was (and still is) teeming with wildlife. We saw minke whales, kittiwakes, murres, and even fish. The Polarstern is extremely popular with birds as it overturns floes and churns up the water, bringing up tasty treats to the surface for them to eat. The water had a greenish color from copious amounts of phytoplankton. Even the sea ice and melt ponds had yellow hues and contained mats of algae. The ice itself was extremely porous and full of holes from the substantially warm temperatures and melt that it has endured.

As we’ve gone deeper into the ice pack, the fog has settled in and the sea ice has thickened. We’ve made good progress through the ice so far, with sea ice concentrations being close to 90 percent, meaning that, within our view, 90 percent of the area is covered in sea ice while the other 10 percent is leads, cracks, and patches of open water. The sea ice is mostly first-year (seasonal) ice, which tends to be easier to navigate through due to it being thinner and structurally weaker. Compared to yesterday afternoon, the ice is rougher. Ice floes have ridged up against one another, blocks of ice are strewn about the surface, and the sea-ice cover looks like a rather challenging obstacle course.

On board, our work has begun, ranging from unpacking and repairing instruments to data processing and site planning. Our days are getting filled with instrument repair and testing, science team meetings, and training sessions as we inch closer and closer to the MOSAiC Central Observatory.

Sea ice geophysicist Melinda Webster is blogging from the RV Polarstern, an icebreaker ship locked in Arctic sea ice for the MOSAiC expedition. Webster will use MOSAiC data as a blueprint to evaluate and extend the seasonal capability of data from NASA’s ICESat-2 satellite for sea ice research.

June 9, 2020

On Monday June 8, we finally left Isfjorden for the Arctic ice pack.

Before that, leg 4 scientists and crew waited about 2-3 weeks aboard the Maria S. Merian and Sonne, which positioned themselves just outside of the mouth of Isfjorden (a fjord in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard). Why? Norway was closed due to COVID-19, and MOSAiC eliminated possible COVID-19 exposure to scientists and crew by keeping us on board. So, we became accustomed to the nice view of Isfjorden, had numerous science meetings, held indoor sports competitions, and took opportunities every day to look for whales passing by.

But why wait 2-3 weeks more after spending two weeks in quarantine on land? It turns out, the Polarstern was making slow progress through thick sea ice. While a thick, compacted sea-ice cover helps its odds for surviving the summer melt season, it’s difficult for icebreakers to navigate through, and sometimes requires backing and ramming to break through the most consolidated areas.

In the wee hours of June 4, we spotted the Polarstern on the horizon. All three ships traveled together into Isfjorden and Adventfjorden to begin cargo, fuel, and personnel operations that morning. Our “handover” would soon begin, which entailed leg 3 scientists sharing as much information as possible with us for locating gear, instrument repair, measurement preparations, data processing, decision-making, reporting, and general life on board. Outside of these technical details, it was simply a joyful time to be with our colleagues after they had spent about four months in the field. We brought them fresh fruit as a treat.

Friday and Saturday were moving days. The crews did a phenomenal job with the logistical operations. The Sonne, which had our atmospheric science team and many crew, saddled up alongside Polarstern to shift cargo, luggage, and personnel across via a gangway and cranes.

On Saturday, it was the Merian’s turn to go alongside Polarstern to carry out the same procedures with the remaining science teams, crew, and cargo. Going on board Polarstern felt immense. Even though it’s slightly larger than the Merian and Sonne, it feels enormous on the inside with passageways snaking through one another. There are numerous labs and containers, and multiple saloons and mess halls.

On Monday, we said bittersweet goodbyes. All three ships left the fjord together, with Maria S. Merianin the lead, followed by Sonne, and, bringing up the end, the Polarstern. Beyond Isfjorden, the ships signaled their horns as a final farewell to one another. The Polarstern steamed ahead while the Maria S. Merian and Sonne turned southward back to Bremerhaven. Although we left in partly sunny skies, the forecast for the evening predicted rough seas and strong winds for the following waypoints of all three ships.

Sea ice geophysicist Melinda Webster will be blogging from the RV Polarstern, an icebreaker ship locked in Arctic sea ice for the MOSAiC expedition. Webster will use MOSAiC data as a blueprint to evaluate and extend the seasonal capability of data from NASA’s ICESat-2 satellite for sea ice research.

We did it. All leg 4 MOSAiC participants passed the coronavirus tests with flying colors. After spending 18 days in quarantine, we departed from Bremerhaven on Monday.

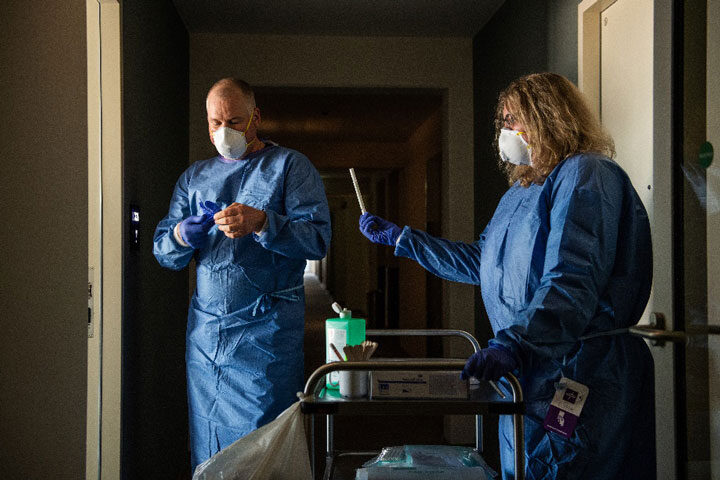

For the most part, everyone treated quarantine as regular work days. The ice team had daily coffee hours, where we virtually got together to learn more about one another, talk about the upcoming expedition, and describe the different views from our hotel rooms. Our meals consisted of meat, fish, or vegetarian based on our selection on our first day. The hotel staff would place our meals outside of the hotel room, knock, and walk (run?) away. They were kind to us. Additional highlights of solitary quarantine include: watching ducks and ducklings, seeing ships going in and out to sea, and admiring the gorgeous sunsets.

By the second week, we had tested negative for COVID-19 twice, which meant we could graduate to group quarantine. Group quarantine consisted of being able to walk outside our hotel rooms and having meals together, but we maintained strict social distance measures at all times and stayed within the hotel’s perimeter. We had 30-minute slots for the gym, held group meetings, and underwent multiple types of training: safety, data management, and communications, all being valuable. Meeting everyone in person and feeling the sunshine and fresh air was an overwhelmingly positive experience.

48 hours before departure, we had our final COVID-19 test and received the results less than 12 hours later. The final day was spent packing, updating software and phone apps, downloading data, and making phone calls to family and friends. We also got our masks ready for the bus journey from the hotel to the two ships, the Maria S. Merian and Sonne.

Now we are in the North Sea, motoring along in sunny and calm conditions. We’re in close communication with the leg 3 ice team, getting ready for the upcoming rotation and finding ways to optimize our limited time with one another. It’s a surreal feeling that all of these moving pieces have come together, despite the challenges, and MOSAiC continues. To the north, we go!

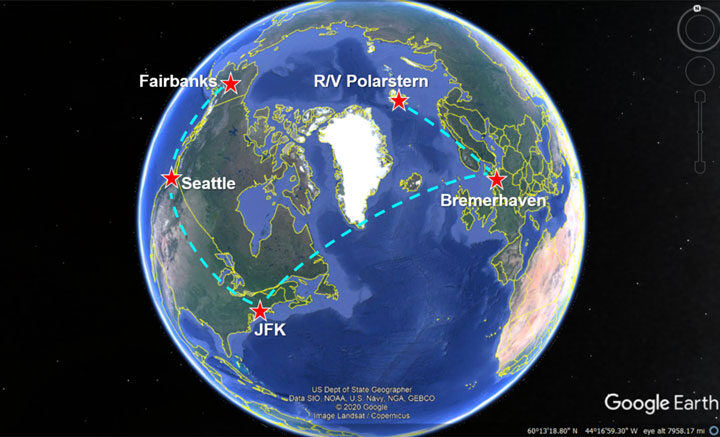

Hi there, from 39,000’. I’m Melinda Webster, a sea ice geophysicist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute. I’m on my way to the Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate (MOSAiC) expedition as the Ice Team Lead for Leg 4. Funded under NASA’s New Investigator Program, I’ll be using MOSAiC data as the ultimate blueprint to evaluate and extend the seasonal capability of ICESat-2 data for sea-ice research.

About 1.5 months ago, I was packed, medically cleared, and ready to fly to the R/V Polarstern from Alaska via Svalbard for the MOSAiC expedition. About 1.4 months ago, COVID-19 was declared a pandemic. Plans set so carefully into place vaporized within a matter of days.

After a false start, packing for a 4+ month expedition gets much easier. You have time to tie up loose ends, have more opportunities to talk with loved ones, and reluctantly finish off projects that were being procrastinated. And, in this case, enjoy the return of spring before heading into a world where the vibrant colors of budding trees and flowering plants are nowhere near. Instead, the Arctic sea-ice cover is a stunning realm with every blue and grey tone imaginable, and is certainly no less beautiful than springtime on land.

The COVID-19 disruptions have also given the MOSAiC Project Board and funding agencies time to compose a logistical masterpiece centered on safely continuing the MOSAiC expedition during a pandemic. Part of this masterpiece ensures that MOSAiC participants travel as safely as possible to the ship to successfully rotate the crew and scientists. Through the National Science Foundation, each U.S. MOSAiC participant for Leg 4 received a care package of personal protective equipment: masks, gloves, hand sanitizer, disinfectant wipes, disposable thermometers, and more. So far, my flights have been at least 50% empty, leaving ample breathing room, and 99% of people have donned masks.

Upon our arrival in Hamburg, we’re to be transported to a hotel in Bremerhaven to start a 2-week quarantine and a series of COVID-19 tests. Once clearing quarantine, tests, and safety training, we’ll take two research vessels from Bremerhaven to Isfjord, the main fjord in Svalbard that leads to Longyearbyen. Although Norway is closed to visitors, we’ll meet the Polarstern in this fjord to carry out the rotation without needing to step foot on land. I anticipate the experience will be overwhelmingly joyful. Our colleagues who set out for a 2-month expedition in February were instead given a 5-month tour due to the pandemic. I’m looking forward to relieving them of their work and continuing the time-series that will make MOSAiC an invaluable expedition and improve our use of ICESat-2 data.