This blog post is the first in a series to come. Our team, the Climate & Ecosystems Change research group from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, is working in collaboration with the Environmental Change Research Unit from the University of Helsinki for a summer with lots of fire field work, science, and adventure. On this journey, our first stop was the Quebec province in Canada. I’m writing this post after our last day of fieldwork here.

The 2023 wildfire season was the largest on record in Canada, with more than double the burned area as the second largest year. In Quebec, an estimated 4.5 million hectares were burned, an area slightly larger than the size of the Netherlands. This record-breaking fire season in Quebec was due to extreme warm and dry conditions. The dense smoke plumes from the 2023 Quebec blazes shocked the world when the smoke reached several cities on the US East Coast, including New York City.

Fellow scientists have been digging deep to understand and explain the phenomena involved in this Quebec fire season. However, as far as we know, estimates of carbon combustion, or the amount of carbon per area burned that is released during a fire, have never been made in Quebec. That’s why we are on it! In loco, since field measurements are a prime way to quantify carbon emissions from fires.

We assess post-fire ecosystem effects to calculate carbon pools below and above ground. In other words, this is the carbon stored in the soil and vegetation. After collecting soil samples and inventorying the vegetation, we can compare burned and unburned (control) locations to estimate how much of this carbon was emitted to the atmosphere due to fire. We do this comparison based on what is called the adventitious root method. On black spruce trees, adventitious roots grow above the initial root collar into the upper soil layers and provide a reference for the pre-fire soil height, as they remain clearly visible many years after fire.

During our expedition, we covered more than 4,000 kilometers on the road. We started by traveling north from Montreal along the James Bay Road and began our sampling at two fires near the locality of Radisson, where the remote Trans-Taiga road was our daily route. We then headed to Waskaganish, on the southeast shore of James Bay, where we sampled another fire. Finally, we ended our campaign at a large fire in the commercial forest near the town of Lebel-sur-Quévillon. All these trips allowed us to make a scientifically interesting transect from North to South in the Quebec province. We also got to know some incredible places, and we are grateful to the people living there who welcomed us.

We were able to observe two different types of intermixed ecosystems in the fires we visited. We found forests dominated by black spruce in peaty lowlands. In drier and often rocky uplands, Jack pine trees dominated. I’m curious to see how these differences will be reflected in practice when we analyze the carbon combustion in these systems.

Our team in the campaign was Lucas Diaz, Max van Gerrevink, Thomas Janssen, Yuquan Qu, and Sander Veraverbeke from VU Amsterdam, and Sonja Granqvist from the University of Helsinki. The success of this expedition is also thanks to our collaborators here in Quebec who helped us during our preparation: Dominique Arseneault (Université du Québec à Rimouski), Jonathan Boucher and Yan Boulanger (Canadian Forest Service), and Fabio Gennaretti (Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue).

This fieldwork is part of my PhD project, so I was responsible for leading and organizing the entire expedition. As hard as it was, the whole process was also a lot of fun. Several times during the campaign, I felt like I was on a holiday road trip with a group of friends. In the end, that’s not entirely wrong. This kind of experience brings us closer to people. It strengthens existing bonds and creates new ones. This great adventure gave me moments that I will remember forever.

Time passes quickly here in the boreal forest. Soon, it will be time to pack our bags and embark on the next stage of this fiery journey. Curious about the destination? Stay tuned!

The Quebec fires expedition is part of FireIce (Fire in the land of ice: climatic drivers & feedbacks). FireIce is a Consolidator project funded by the European Research Council. FireIce is affiliated with NASA’s Arctic-Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE). This blog post was written by Lucas Ribeiro Diaz, a Ph.D. student at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, studying Arctic-boreal fires by combining field and remote sensing approaches.

On a blustery March morning, Petya Campbell stood atop a 204-foot-tall tower and looked across the waving canopy of the leafless deciduous forest at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center in Edgewater, Maryland. This forest is predominately tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), and the tower extends over trees that are over 120 feet tall.

Petya, from the University of Maryland Baltimore County and NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, is working with Greg Cain, a master technician from the Battelle-managed National Ecology Observatory Network (NEON)—the U.S. National Science Foundation-funded program that runs the tower at the Smithsonian site (SERC). Petya and Greg were on the tower that day to install a new type of instrument, an automated spectrometer called a NoX (Near Infrared Box). The NoX measures the light reflectance off the forest canopy in hundreds of narrow spectral bands through the visible wavelengths we can see and into the near-infrared bands beyond our vision. The instrument will make these measurements every few minutes throughout the entire growing season.

In addition, NEON runs instruments on this tower that take measurements of the movement of carbon dioxide (CO2) into and out of the forest. CO2 is absorbed from the atmosphere into the trees through photosynthesis, so measuring the amount of CO2 taken up by the plants is a measure of forest productivity. These CO2 flux measurements are collected continuously and reported every half hour.

The time series of spectral reflectance measured by the NoX can provide information about leaf characteristics. For instance, it can tell scientists about the amount of green biomass and chlorophyll in the leaves, which determines the potential productivity of the forest; the amount of other leaf pigments that are used to protect the leaves from damage, which indicate when the trees are under stress; and the amount of water in the leaves, which can be used to detect drought stress.

Researchers will use data from the NoX to gain insight into the functioning of this deciduous forest as it responds to environmental conditions such as hot or cold spells, droughts or rainy periods, and sunny or cloudy days. They will observe seasonal changes from the time the leaves emerge in the spring, through the green of the summer, the changing colors of the autumn, and finally the loss of the leaves at the end of the growing season. Others can watch the forest change through the seasons using the phenocam, a web camera mounted on the tower that regularly takes photographs to monitor the changes in the forest.

Installing the NoX on the SERC tower is just the most recent deployment by Petya Campbell and Fred Huemmrich. Over the past couple of yeavrs, they have installed similar instruments on flux towers in the arctic tundra and boreal forest.

The NoX data will be compared with the tower flux data to develop and test relationships between spectral reflectance and forest productivity and the detection of stress responses under adverse conditions. Understanding these types of relationships and how they may differ between vegetation types and season will aid the development of future NASA missions such as the Surface Biology and Geology (SBG) study, and the Geosynchronous Littoral Imaging and Monitoring Radiometer (GLIMR), which will collect spectral information similar to the NoX over large areas of the Earth.

Fieldwork notes, July 21-August 3, 2023

Summer fieldwork for our project, “Clarifying Linkages Between Canopy Solar Induced Fluorescence (SIF) and Physiological Function for High Latitude Vegetation,” once again took our team from University of Maryland Baltimore County north to the boreal forests of central Alaska. We visited this area in the spring to collect data during the very start of the growing season, and now we are returning to collect data during the peak of summer.

This project is part of the NASA Terrestrial Ecology program’s Arctic-Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE). The goal of ABoVE is to improve our understanding of high latitude ecosystems, how these ecosystems respond to climate change, and how satellite data can provide information to describe ecosystem processes and aid management decisions.

Our study focuses on measuring light emitted by plants called solar induced fluorescence. Green leaves absorb light, and through photosynthesis take in carbon dioxide and water and produce oxygen and sugars. Fluorescence occurs during photosynthesis as some of the absorbed light energy is radiated out from the plant. The amount of light fluoresced is only a very small fraction of what is absorbed, which is why our eyes don’t see plants glowing. In our study, we use sensitive instruments that can detect this fluorescence. Our goal is to better understand the sources of fluoresced light and how to use this information to describe productivity in boreal forests and tundra.

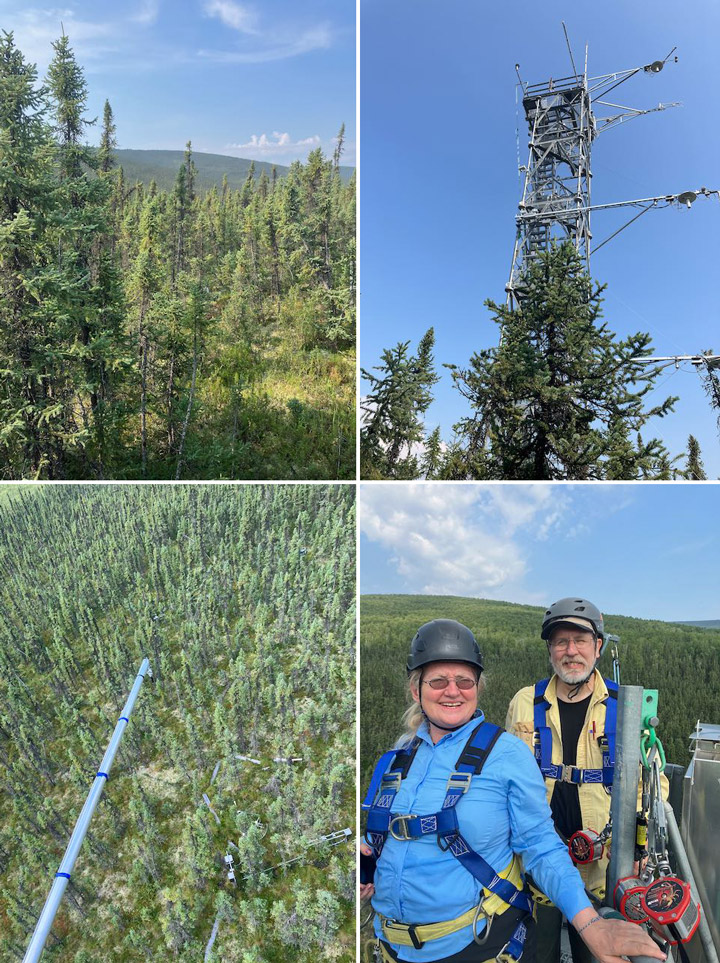

Our study site is at the Caribou Creek flux tower run by the National Science Foundation’s National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON). In spring, we deployed automated instruments at the NEON tower site that continuously collect data. On this trip, we are checking on how they have been working.

In July there was a big change from our previous visit in April. In April, the area had a deep snow cover with temperatures dropping below 0°F, while during this visit the daytime temperatures were in the 80s F and the ground was now all green (images below).

On the top of the tower we have an instrument called a FLoX (Fluorescence Box). The FLoX views a patch of forest from above, and every few minutes during the day it measures the reflected light and solar induced chlorophyll fluorescence. This provides us with a description of plant activity at different times of the day through the growing season (images below).

Also at the site we have monitoring PAM (MoniPAM) instruments attached to shoots of the spruce trees. The MoniPAM probes shine pulses of light at individual spruce shoots to measure fluorescence and photosynthetic processes at the leaf level (images below). We put blankets over the probes for a while to dark-adapt the shoots to measure their response when unstressed. In the spring, we put the MoniPAM probes in easy-to-reach places when there was a lot of snow on the ground. On this trip, when we returned to check them in the summer, we found we had to really reach up to get them without the snow to stand on.

From the ground, we collected reflectance and fluorescence measurements (similar to the data collected by the FLoX) of individual plants in the FLoX field of view and a variety of representative plants in the larger area surrounding the tower. These measurements will help us understand the local variability (images below).

A lot of the ground cover was cotton grass (Eriophorum spp.) that forms tussocks, which are tight clumps of grasses. The tussocks made walking through the area difficult, like walking on half-buried basketballs, so it was easy to twist an ankle, especially with a heavy backpack spectrometer on your back.

We collected branch samples to make measurements of leaves and needles that we will use to parameterize models of vegetation fluorescence and productivity (images below).

We took a little time off to visit some other places in the area. We saw musk ox, which are animals of the tundra but raised in captivity at the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Large Animal Research Station. Their thick, shaggy coat keeps them warm through the frigid arctic winters. Under the long guard hairs is a soft wool called qiviut that musk oxen shed in the spring. Qiviut can be spun into a very warm and soft yarn. Small balls of qiviut yarn can sell for over $100.

On our last day in Alaska we visited the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) Permafrost Tunnel Research Facility (images below). Permafrost refers to soil that has been frozen continuously for more than two years. The permafrost around Fairbanks, Alaska, is considered ‘warm’ (at a temperature of -0.3oC/-0.4oC) as compared to the permafrost in our other study site in the North Slope of Alaska at Utqiagvik (e.g., a temperature -3oC/-4 oC). This warm permafrost is very sensitive to the changes in soil temperatures that can result from fires, rain events, and other disruptions that can cause permafrost thawing. Thawing permafrost can result in damage to roads and buildings and cause disturbance in forests.

The permafrost tunnel is dug into a hillside through earth that has been frozen for thousands of years. The tunnel reveals bones of extinct ice age animals, plants preserved since the ice age, and large ice wedges that can take hundreds to thousands of years to form. The ice wedges cause the formation of polygonal patterned ground, where the ground surface is covered with a pattern of shapes of slightly higher or lower ground. Our study site in Utqiagvik was in an area of high centered polygons, so it was interesting to be able to actually see the shapes of the underground ice that formed that unique landscape.

I’m writing this post on our last day in St. Mary’s, Alaska. This tiny village of about 560 inhabitants had its surroundings ravaged by two large tundra fires in the summer of 2022. The East Fork fire was the second largest tundra fire in Alaska in over 40 years and the biggest in Southwest Alaska. These events were historic, and I could start this post by writing about the intense and productive three weeks of work we had here. However, this whole project started much earlier.

I started this Ph.D. with plans to do field work in Siberia. However, halfway through, due to the pandemic and geopolitical issues, I saw all those plans slip through my fingers. Despite being from a country with among the greatest biodiversity in the world (Brazil), the arctic-boreal environments have always fascinated me. So in the winter of last year, when I came across these fires while analyzing satellite images, I knew this was a unique opportunity to pack my bags and finally be in the tundra. I remember showing the first satellite images and data of these fires to my supervisor, Dr. Sander Veraverbeke, and he confirmed that these fires were indeed scientifically very interesting and logistically feasible for our expedition. From then on, a long process of preparation began.

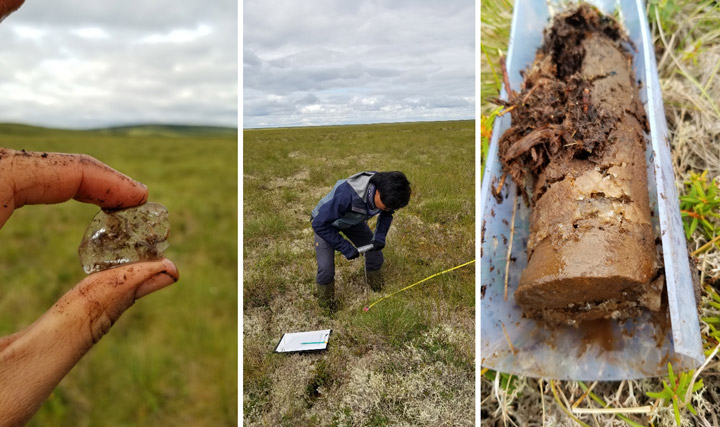

As this field campaign is part of my Ph.D. project, I was responsible for planning both the scientific and logistical aspects. Now, reflecting after the final day of sampling, it is incredibly rewarding to see that the planning has paid off. We sampled 11 days by boat along the Andreafsky River sampling the East Fork fire and another five days by helicopter sampling the Apoon Pass fire. Our main goal was to estimate the carbon combustion from these fires, that is, the area-normalized emissions in grams of carbon per square meter. Field measurements are the prime way to accurately quantify carbon combustion. To do it, we collected soil samples and estimated the burn depth of the soil organic layer. It is crucial to advance the quantification of tundra fire carbon combustion and understanding its environmental drivers.

In addition to carbon emissions, another key point of our expedition is to understand the effects of fires on permafrost. Previous research has shown that fires in the boreal forest increase the thaw depth of the active layer above permafrost, which can lead to permafrost degradation. We are curious to investigate this mechanism in the tundra, even more so now that we have found ice-rich permafrost during our fieldwork.

But it was not just the work that was amazing during this campaign. The tundra landscape was always breathtaking. Both from above with the helicopter and along the river from the boat. We were presented with a stunning rainbow on our first day using the helicopter. Wildlife was always around: moose, bears, beavers, eagles, geese, and countless other bird species.

Lucas Ribeiro Diaz, Max van Gerrevink, Rebecca Scholten, Sonam Wangchuk, Thomas Janssen, Thomas Hessilt, and Sander Veraverbeke were part of this field expedition. Our team is part of the Climate & Ecosystems Change research group at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. However, the success of this campaign would not have been possible without the help of our boat driver, David ‘Matty’ Beans, and our helicopter pilot, Savanna Paulsen. We are also grateful to the city of St. Mary’s and its people for warmly welcoming us during these weeks. Finally, Dr. Lisa Saperstein from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Alaska has provided tremendous help when we were organizing our campaign.

45 plots, 1,383 tussocks measured, 255 soil samples, 495 thaw depth measurements—numbers like these make us believe that we have just concluded a field campaign on some of the most densely sampled tundra fires in the history of science. Now, we have three more weeks of work ahead of us at the USGS soil laboratory in Anchorage. With lots of ideas in my head, I’m excited to see the new findings this valuable data can reveal!

I have just finished writing this post and I realize that perhaps it is too personal. But it could not be otherwise. Our science often blends in with who we are, our dreams and expectations. I leave St. Mary’s feeling fulfilled, I think I have always dreamed of being here. I leave the tundra sure that moments like this are the reason I decided to embark on this journey of doing research.

This tundra fires field expedition is part of FireIce (Fire in the land of ice: climatic drivers & feedbacks). FireIce is a Consolidator project funded by the European Research Council. FireIce is affiliated with NASA ABoVE. This blog post was written by Lucas Ribeiro Diaz, a Ph.D. student at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, studying arctic-boreal fires by combining field and remote sensing approaches.

Just like the undulating terrain of the tussocky tundra we traverse, our days also take unexpected twists and turns. After a beautiful last day of sampling the East Fork fire scar along the Andreafsky River, where three moose visited us and delivered a personal goodbye, we were all excited for our first day of sampling the Apoon Pass fire scar via helicopter. But our spirits were momentarily dampened by news of Savanna, our pilot flying in from Nome, getting stuck in a thunderstorm on her way to our base in St. Mary’s, Alaska. Her arrival, delayed until early afternoon, was just the prelude to a challenge-laden morning.

Further issues emerged with our satellite communications device, requiring transatlantic collaboration with our colleagues in Amsterdam (many thanks to Thomas for his unwavering support!) These obstacles left us momentarily uncertain about the feasibility of flying at all that day. Miraculously, by 2 p.m., the looming cumulus of problems and bad weather began to disperse, and by 2:30 p.m., with a renewed sense of purpose, we embarked on our mission to sample the second fire of our field campaign.

The flight itself proved to be a standout experience, treating us to a breathtaking panorama over the hilly tundra that we had sampled along the Andreafsky River in the preceding days. The Apoon Pass fire scar, though not far from the East Fork fire, is geographically quite different, as it is located in very flat lowland terrain. Flying over the last crests of the hill range provided a captivating sight of the vast lowlands extending in all directions.

To our surprise, we were only able to spot the difference between burned and unburned tundra when descending to a relatively low altitude. This observation, together with the satellite imagery prepared by our campaign lead Lucas, led us to an initial conjecture that fire severity would be lower than what we had previously seen.

To systematically assess fire severity and carbon emissions in our plots, we are following protocols established by Mack et al. (2011) and Moubarak et al. (2023) for tundra fires in Alaska. We use two independent methods to estimate the burn depth based on the height of tussocks and Sphagnum (peat moss) patches in our plots. For the tussock-based method, we compare the height of tussocks that survived the fire with the height of tussocks in unburned locations. This gives us an estimate how much duff and other organic material has been combusted. For the Sphagnum-based method, we connect different moss patches of similar height with a thread and measure the distance from the thread to the surface at 25-centimeter intervals. This will give us an overview of the variability in burn depth within our sampling locations.

These two measurements will allow us to quantify the amount of carbon combusted per plot, which we can relate to the satellite imagery, as well as to the thickness of the active layer we are measuring at each plot to assess how the fire is affecting the permafrost.

In the end, to our surprise, our first helicopter day turned into one of the best sampling days we had during the campaign so far. We were gifted with beautiful, sunny weather until 9 p.m., and sampled even more plots than we had initially expected. We have now become a well-oiled machine, capable of sampling a plot within a mere hour and a half. Having the helicopter with us at all times offered an invaluable advantage—the ability to swiftly transport parts of our team to nearby sampling sites. After having returned to our base, we are excited for another day in the beautiful tussock tundra of southwestern Alaska—keeping our fingers crossed for another couple of days of good weather!