By Ludovic Brucker

After an unexpected phone call from the helicopter pilot on Easter Sunday, Ludo and Clem ended the second season of the Greenland aquifer campaign, with the support of Susan, Rick, Lora, Bear, the weather office, and many others. Thanks all for this Easter bunny.

We still wonder whether our campaign was successful, or fair. For sure, it was a mix of good and tough times.

The pluses, making our campaign a good time:

– We’re back from our field site, healthy and with all our fingers and toes!

– We set up an almost perfect camp, limiting drift considerably.

– Our two tents survived 65-knot winds!

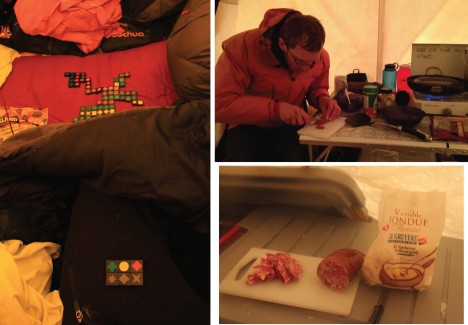

– We had saucisson (dry cured sausage), and cheese for fondue!

– No polar bear smelled our food!

– We collected over 17 miles (28 kilometers) of high-frequency (400 MHz) radar data, including 12 mi (20 km) in one day (equivalent to half a marathon!)

– Along a 1.24-mi (2-km) segment of the 2011 Arctic Circle Traverse, we deployed 5 radars operating at 400, 200, 40, 10, and 5 MHz.

– We installed an intelligent weather station developed by the group at IMAU, in the Netherlands.

– We drilled down to 28 feet (8.5 meters) to record the density and stratigraphy of the ice layers.

– We have GPS taken positions during a week, which will help us calculate the velocity and flow direction of the ice in this basin.

The minuses, making our campaign “different”:

– Ten days of weather delays before the put-in flight to our ice camp location.

– Rick could not make it to the field with us.

– We never had three consecutive half days with weather suitable for work.

– Getting a sore throat from shouting to hear each other less than a meter apart.

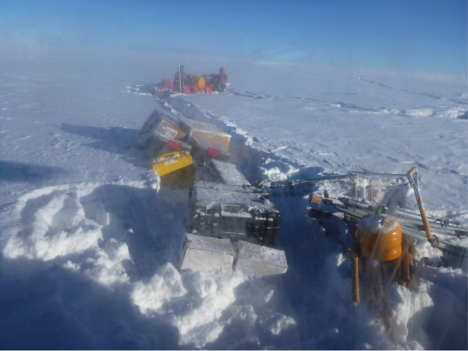

– During the one day of great weather, we tried to drive down a pilot tube to install a piezometer in the aquifer. This technique is adapted for ground water found within rocky soils. It was the first attempt to do it in the Greenland firn. Driving the metal pipes in the snow through the ice layers was a nightmare, we had to pound on those pipes really hard to make them go through the thick ice layers and we ended up breaking them. At one point, we thought it was broken slightly deeper than 6 ft below the surface, so we dug a pit down to fix it. Well, it turned out that the broken piece was actually 13 ft down — we spent the only full day of great weather breaking our equipment.

– We ran out of cheese for fondue, and of saucisson.

– Sunscreen was completely useless this season.

The “funny” stuff:

– 30 m/s wind is brutal, though not necessarily hilarious.

– High-wind speed does not make the clock spin faster, only the anemometer.

– Supporting text messages and jokes from our family, colleagues, and office mates.

– Attempting a radar survey with a sled taking off every other gusts.

– Calling the Met Office for a weather forecast: “Hello! Since it’s windy here we are wondering what will happen in the next 36 hours.” “Yes, I can confirm that you are experiencing wind.” “Thanks so much for the confirmation, but there was no room for doubt.” “Oh, but it’s a nice spike on the computer screen! It won’t blow more, but it won’t stop soon. Be careful out there”. Patience with Mother Nature is the #1 fundamental.

– Coastal storms from the East might be our favorite storms on the ice sheet: wind stops, and temperatures increase, but it snows, snows, and snows.

– Sixteen feet of seasonal snow is deep, especially with the top 2 feet of fresh snow becoming harder and harder as they it gets compacted by the wind.

– Excavating 1765 cubic feet of snow between 8pm and 11:30pm (you got to use the weather window whenever you have it.)

– The frost all around our sleeping-bag head every morning.

– The 40 hours laying down in the sleeping bag.

– The melody of the wind on our tents and through the bamboo sticks we stuck around them.

– Using the sleeping bag to store hats, balaclavas, gloves, socks, boot insulation, contact lenses, tooth paste, sun screen (it was nice to dream about the day we would need it), batteries, head lamp, snacks, water bottles (ideally liquid and not spilling.)

– The pilot phone call at 8 am on Easter Sunday: “Good morning, happy Easter! Don’t go for a ski strip today, we will come pick you up in 3-4 hours!”

This was the synopsis of our 13-day adventure on the ice sheet. Even though we have been pulled out from the ice sheet, we still have some work to do, such as cleaning and drying our cargo and repackaging it for shipping to either Kanger, or the US.

Now, we would like you to enjoy some photos taken in the field. Thanks again for spending some times reading the blog and following us! Until the next campaign, enjoy each season and stay warm! As we say in French: “En Mai, fait ce qu’il te plaît!” In English, it translates to something like: “In May, do as you please!”. Yup, we’re heading back to the office and will hide behind a computer screen for the months to come.

All the best,

Ludo & Clem

(Left) As weather-delay days continue to keep us in town, Rick calls the weather office to assess whether we can afford to spend more days waiting to be deployed on the ice sheet. (Right) The saddest moment of our campaign, when Rick had to remove his gear from our cargo because he wasn’t coming with us to the field.

(Left) At the Tasiilaq heliport, Ludo waits for our put-in flight on the cargo. (Right) The Air Greenland B-212 helicopter with blue skies and high clouds. After 12 days of patiently waiting, it looks like it’s a go!

(Left) Our cargo, dropped almost two weeks ago, got buried under 2 feet of snow. But all the pieces were there! (Right) The B-212 landed near our cargo for a final move to the ice camp location.

Minutes after the B-212 had left Clem and me on the ice sheet, we were already shoveling the fresh snow to install our cooking and sleeping tents before dark. This was no time for play, this was no time for fun, there was work to be done.

Shoveling, a typical activity at camp. Luckily this year we did not have to shovel too much to maintain our tents.

With the amount of fresh snow and the katabatic winds increasing, snow dunes were forming perpendicular to the direction of the wind — it was like being at sea! Half a day later, sastrugis developed along the wind direction and snow became hard and compact.

Ludo inside a 2-m-deep pit dug with the hope to repair a broken pilot pipe for installing a pressure transducer in the aquifer.

Ludo, inside a larger 2-meter-deep pit dug after dinner with easterly winds increasing as another coastal storm was coming bringing more snow. Our rationale was that the sooner we dug, the less snow we’d have to remove.

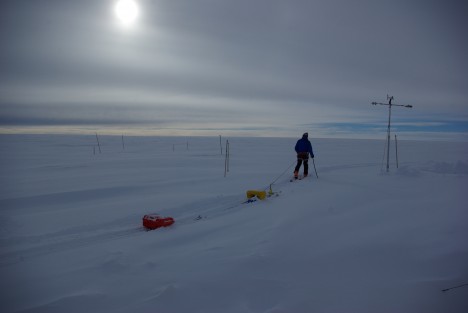

Two hours before being pulled out from the field, Clem was dragging the 200 MHz radar, and carrying a GPS unit.

(Left) Snow accumulated on our tent entrance overnight. We monitored it carefully every half hours from 2 am to the late evening. We took care of it a couple of times! (Middle) Clem calling the weather service to find out what wind speeds would hit us during the night. (Right) Our last saucisson, hanging over the snow/water pot.

Clem uses an evening break in the weather to drag a low-frequency radar in the fresh snow deposited in the previous hours.

Weather was clement enough with Clément to allow him for a pit stop during our half-marathon radar day around camp.

A new day, different weather, and another attempt to collect more radar data. Since we aimed at collecting surface-based radar data, not airborne radar data, we quickly had to stop because the wind would make the radar system take off with every other gust.

Pictures taken just one hour apart. In the top one, we were setting up a radar system. In the bottom one, we were actively wrapping it due to sudden katabatic winds that picked up in less than 10 minutes.

Indoor activities while the winds prevented us from working. (Left) Playing domino with mitts in a shaking tent, unforgettable times! (Right) Good food to keep us happy. Merci maman for thinking about us before leaving home.

Our flight back had already been canceled twice. It turned out that this was our last evening at camp. We had a total of two pretty sunsets: one on the first day and the second 12 days later, on our last evening.

Forty minutes after leaving our camp, we see signs of life: a view of Tasiilaq (top) and Kulusuk (bottom), minutes before landing.

We’d like to finish with this quote from the French explorer Jean-Baptiste Charcot, who led the second French expedition in Antarctica around 1910:

“D’où vient l’étrange attirance de ces régions polaires, si puissantes, si tenaces, qu’après en être revenu ou oublie les fatigues, morales et physiques, pour ne songer qu’à retourner vers elles? D’où vient le charme inouï de ces contrées pourtant désertes et terrifiantes?” (“Where does the strange attraction of the polar regions come from, so powerful, so stubborn, that after returning from them we forget the fatigue, moral and physical, only to think of returning there? Where does the incredible charm of these lands come from, however deserted and terrifying?”) Jean-Baptiste Charcot, Le Pourquoi Pas?

By Rick Forster

Our team finally made it to the ice sheet on April 8, after being delayed for almost two weeks due a series of storms. That day, we awoke to patches of blue sky over the village of Tasiilaq and were eager to get to the heliport for our scheduled 11:40 AM flight to the ice sheet. Lingering clouds over the ice sheet delayed our departure about three hours.

The village of Tasiilaq on the day of our flight to the ice sheet in SE Greenland where the Air Greenland B-212 helicopter is based. (Credit: Rick Forster.)

Once we saw the Air Greenland helicopter returning from its last trip to the local settlements for the day, we knew our flight was next. The trip to our research site on the ice sheet takes about 30 minutes.

The two-week weather delay meant I had to return to the University of Utah while Clem and Ludo would stay on the ice sheet for about 10 days to gather data and perform experiments on the Greenland aquifer. It was a hard decision to make, but I had commitments and if I stayed with the team on the ice sheet, we would all have to leave before all the science could be completed. Ludo and Clem’s schedules were more flexible so they will be able to extend their trip to spend extra time on the ice. I went with the team to the ice sheet to help unload the camp gear from the helicopter at the research site.

From left to right: Clément Miège, Ludovic Brucker, and Rick Forster happy to be finally boarding the helicopter for the flight to the ice sheet. (Credit: Rick Forster.)

The flight to the site was spectacular, going over sea ice chocked fjords and outlet glaciers draining the ice sheet.

An outlet glacier draining the Greenland ice sheet into an ice covered fjord. The individual rough blocks of ice within the smooth surface of the frozen fjord are icebergs that calved off the glacier last summer and are now trapped in the winter fjord ice. (Credit: Rick Forster.)

Once at the research site, our team, including the pilot and flight engineer, quickly unloaded the cargo from the helicopter. The heaviest gear could be left closer to the helicopter, while the lighter pieces needed to be dragged farther away and held down by Ludo and Clem to keep them from being blown away from the winds generated by the helicopter taking off. The ice sheet surface was smooth and soft with knee-deep powder, great for skiing but not so good for moving cargo and setting up camp.

Clem, Ludo, and the science and camp cargo waiting for the helicopter to take off. (Credit: Rick Forster.)

Clem and Ludo will spend the next week and half gathering additional data on the Greenland aquifer from a variety of ice penetrating radar systems and installing an automated weather station for our colleagues at Institute for Marine and Atmospheric research Utrecht.

By Clément Miège

It might be hard to believe but yes, we are still in town! We have been delayed for a full week now, every day getting ready for a possible flight the next day, and every morning, we get the same message: “Unfortunately, there will be no flight to the ice cap today due to weather and bad visibility with low clouds, but tomorrow looks more promising.” Oh, no! Even if it is fully justified, it is always a bit disappointing the moment you hear that, but I think our team has a good experience already with this kind of delay and we are able to switch quite easily and still be happy and optimistic for a flight the next day.

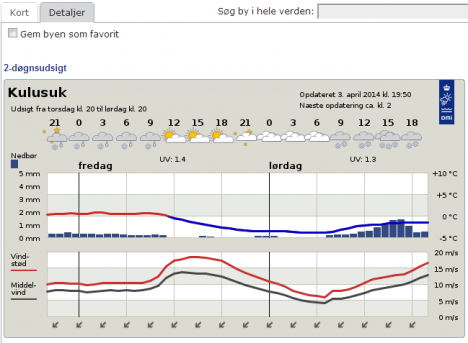

The main helping factor that puts us back in a good mood comes from the weather forecast. Indeed, every day we are able to see a clear-sky window that makes us think that we will be able to fly the next day. Sometimes, this weather window can be very tiny, but it is always there! Good spirits!

Tomorrow, again, it looks great, with a weather window in the afternoon (Forecast provided by the Danish Meteorological Institute .)

When you look at long-trend forecasts (beyond the following 48 hours), the weather is changing a lot in short spans of time. Often, there are significant changes from one forecast to its updated version a couple of hours later. For example, a 5-day storm, with heavy precipitation, appears in the forecast, but then it it is removed from the next update. So our moods shift quite a bit. For even longer trends, it becomes a different story. Rick shared with Ludo and me his experience with the so-called “Canadian Forecast”. It consists of making the last 5-6 days of a 14-day weather forecast always be nice and sunny, to keep people happy through the winter so they can anticipate the end of it. We can verify this “happy weather trend” in Greenland with our own Danish Forecast — the five last days of this forecast are always sunny. We are keeping a record of the forecast since we arrived two weeks ago, and we can say this is a regular pattern.

After checking weather forecast here, our daily duties are not done yet! Next, we take a look at the data from a weather station that is currently in the field, in our future camp site. We dropped the weather station as part of our cargo last week, but we did not have time to set it up. It is however transmitting data and our IMAU colleagues gave us access to the transmitted data. Unfortunately, the signal for diurnal temperature is getting weak, it’s almost nonexistent anymore, which means that the weather station is getting buried. More and more snow will need to be removed to access our equipment when we will get to camp (maybe tomorrow?) Next, we take a look at the Kulusuk airport’s flight schedule for the day. We can see for example that the Tiniteqilaaq flight is canceled (“aflyst”, in Danish) and that the Isortoq flight is delayed. Then, we do the same thing for the Tasiilaq heliport schedule and then we speculate (while drinking our coffee) where our flight fits in this schedule. We are getting quite good at this exercise! Our flight never fits and we are always rescheduled. But there are some events that are still out of our control. Three days ago, a domestic conflict in Kuummiut required the police Marshall to solve it. Since the Marshall is based in Tasiilaq, the helicopter had to fly him there. That day we had woken up at 5:30 am for a flight scheduled to leave at 7:05, which got rescheduled to 11 am, and after three additional hours waiting at the airport, it eventually became a cancelled flight. Needless to say, the helicopter never made it to the Kulusuk airport. We simply went back to the hotel in the pouring rain. As Ludo likes to say: “This is again craptastic; good times!”

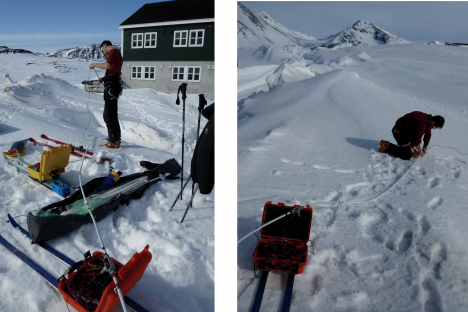

Sunday (March 30) was a beautiful day though, but we were not on the flight schedule — the pilots had to catch up with the Saturday flights had been cancelled. We took advantage of the nice weather to further test our field equipment. As I mentioned in an earlier post we will be testing a low-frequency radar system in the aquifer region on the ice sheet. Laurent Mingo at Blue System, who develops the IceRadar is letting us test a beta version of one of his radar systems. The IceRadar is currently used by many research groups on alpine glaciers, ice caps and ice islands. As such, it has been deployed in many regions of the world (Yukon, Rocky Mountains, Himalaya, Bhutan, Iceland, the Andes, the European Alps…) to perform ice thickness measurements and bed mapping, but also to look at the glacier englacial properties. I believe this is the first trip for the IceRadar to the Greenland ice sheet. So we are quite honored to have this system with us to try it over the aquifer.

Setting up the IceRadar for the first time in Greenland, with the 5 MHz antennas. The lower the frequency used for the radar, the longer the antenna has to be. For a 5MHz system, the antenna length is 20 meters (about 70 feet), and there are two of them (receiving and transmitting). (Credit: Rick Foster)

After the setup, we try our radar going from the seasonal snowpack to the relatively thin sea ice – that gives us important changes in terms of dielectric constant, which look quite obvious in the radar profile. The system total length is about 50 meters (164 feet), so no sharp turns are allowed! (Photo credit: Rick Foster.)

Getting the 40MHz IceRadar ready, you can see the difference of the antenna size — this is definitely easier to turn. (Photo credit: Rick Foster)

Rick watches Ludo and me maneuvering the IceRadar from the hotel. A new (feline) friend is also observing us, probably wondering what we are doing here! (Credit: Rick Foster.)

At the end of the day we have great news: the IceRadar is working well at the two frequencies tested, which is really promising toward our ice sheet measurements. YAY!

Finally, the hotel still does not have running water. As Ludo mentioned in an earlier blog post, the heating element in the water pipe supply line that prevents the water from freezing broke. And the road to get to the lake with fresh water is still being plowed, but the bad weather and drifting snow prevent the plow truck from making much progress. We are getting used to showering with a water bucket and becoming more and more efficient at conserving water.

Without water at the hotel, we are even more motivated for going to the ice sheet since we know we will not be missing a good hot shower anyway.

Our team has a really good feeling for tomorrow, so let’s hope for a “go” and keep our fingers crossed!

Cheers, Clément on the behalf of the aquifer team.

By Ludovic Brucker

Kulusuk, 31 March 2014 — When I started writing this post, my opening was: Greetings from (still) white-out and windy Kulusuk 🙁

Updated opening sentence: Greetings from now rainy Kulusuk 🙁 🙁

The nice thing about weather forecasts is that they change all the time, so you never get bored watching them. The bad thing about weather forecasts is that they change all the time. What we have been experiencing over the past days was bizarre. We had a storm with sustained high winds and some gusts. We then had temperatures high enough to work outside without a jacket. We also had calm periods alternating every half hour or so with sustained gusting events, so intense that it wasn’t advisable to get near the windows. Now, it is raining.

We spent the last couple of days patiently waiting a phone call or an email. During these days, we made sure to be able to arrive at the airport ready for a put-in flight within an hour notice, if necessary. So far, a good weather window coinciding with availability of the B-212 helicopter and its crew has not happened. We like to think that we will have a flight tomorrow morning. This might happen. As Daniel L. Reardon said: “In the long run the pessimist may be proven right, but the optimist has a better time on the trip.” We are optimists, despite the weather teaching us to be realists.

In the mean time, at the hotel… there is no (liquid) water available anymore since Friday. The pipes bringing the water from a nearby lake are frozen, due to an issue with the pipes’ insulation. This sounds typical here, but usually the hotel’s water tank can get refilled with a winter water truck (please, don’t ask for details, I tried to understand but couldn’t figure this story out completely). But now the road (the only one road) is buried under more than 2 meters of drifted snow. Hence, the winter water truck cannot resupply the hotel’s water tank. We were preparing to melt snow. As Rick thoughtfully mentioned it at breakfast this morning: “if you can’t get to the field, the field will come to you” © Rick Forster. However, the hotel employees went to pick up some big jugs of water for drinking, cooking and even showering at the village! Our record is less than 2 liters used per shower. The colder the water, the less you use of it.

Today, we moved the rest of our cargo up at the airport, including our personal bags. We are really hoping to go to the field soon (that is tomorrow early morning). Keep your fingers crossed for us! Signed: Ludo, one of the three optimists.

By Ludovic Brucker

Kulusuk, 29 March 2014 — For our deployment to the field, we need two flights to bring our scientific equipment and camping gear. As mentioned in our previous post, we decided to avoid being on the ice sheet while the third storm system of the week affects the area. However, thanks to Air Greenland and its helicopter B-212’s crew, we were able to have a first cargo flight to the ice sheet on Thursday afternoon. This will allow us to be fully operational as soon the second flight brings our tents, food, more science gear, and us to the ice sheet!

Thursday morning, we went to the airport to meet with the pilot and hear his point of view about a possible cargo flight that same day. While snow-removing activities of the runway were underway, he shared with us his concern that our cargo (if left on the ice sheet with the current weather system developing offshore) may be blown away or heavily buried in snow. Since we did not have a single item fly away in Antarctica during our SEAT 2011-2012 traverse and its Christmas storm, we will make sure this does not happen in Greenland! Regarding buried items; it’s fine as long as the shovels aren’t buried themselves.

A snow plow removes snow from the second storm of the week at the Kulusuk airport . (credit: Clément Miège.)

In the afternoon, Clem and I took off with the cargo flight to unload it from the helo, and to build the cargo line. The sky was scattered with clouds, sometimes low, but it cleared up as we were approaching the ice sheet.

Transit from Kulusuk to our ice sheet location, near the settlement of Tinitequilâq. (Credit: Ludovic Brucker.)

We landed in the vicinity of our temperature probe system and its Argos antenna, which has been sending temperature measurements every day for almost a year now. With the help of the helicopter’s crew, it did not take long to organize a cargo line along the dominant wind direction to minimize snow drift.

Our cargo line on the ice sheet, near the temperature probe and Argos antenna we left behind in 2013. I’m finishing up by deploying a second cargo strap across the line and through the boxes handles. (Credit: Clément Miège)

Our objective was accomplished, the cargo was on the ice sheet. Step 1: Done! Done? Well, of course not. We still had to fly back… But in spite of everyone’s effort, we were not able to fly back to Kulusuk that day. The night was coming quickly and the pilot is not allowed to fly after twilight. Thus, we landed in Tasiilaq 3 minutes after twilight on Thursday. Tasiilaq is on the other side of the bay from Kulusuk, a 15-minute helicopter ride away. Tasiilaq is the largest city on the East coast of Greenland, with about 3,000 inhabitants, and it’s home for the B-212. We landed accurately on the B-212’s kart in front of its hangar so that it could be moved inside quickly. Suddenly, Clem and I were facing a situation for which we were not prepared.

For a less-than-2-hour round trip to the ice sheet, Clem and I were dressed in our warmest layers, and to face a variety of eventualities (including spending an unexpected night on the ice sheet) we had packed a tent, sleeping bags, food, water, extra jackets, gloves, goggles and hats, a satellite phone, two GPS, and a beacon locator. We knew that in our cargo there was more food, a cook stove, propane and white gas; these were in case for the inbound flight. For the outbound flight, we knew that the B-212 has some safety equipment too. That was all we had. But we were facing a different situation now: we were in the largest town of East Greenland, with the perspective of a storm arriving overnight, and forecasted to last several days.

Air Greenland found us a hotel and a warm dinner. Sweet, we wouldn’t be camping on the helipad. Past the first night, we woke up with the exact same landscape as in Kulusuk. I’m serious! Through the windows we could see the same white sky, land, and horizontal snowfall. Visibility? We still don’t know for sure; neither Clem nor I could tell because we had left Kulusuk with our contact lenses on and did not carry our glasses.

Past this first reality check, we headed to breakfast (dressed in our long underwear). We had a specific topic to discuss: what were we going to do during the next hours, days, week? The ideas ranged from finding a book, a toothbrush, an Internet connection, an alternative to water for our contact lenses, learning Greenlandic, finding a boat… Three hours after breakfast, we started a hunt for a set of playing cards to play cribbage. I asked the hotel manager if we could borrow cards from the hotel, or any other game that would keep us busy a few hours, days, a week. He pointed out a souvenir store where we could buy such items. Well, despite knowing that one should take his passport to the field, we did not have money. The hotel manager had a swift idea: “That’s not a problem, you can wash dishes after lunch.” Good times! So, we registered for being the little hands in the kitchen. The next 15 minutes were funny, I was trying to explain this to Clem, and to convince him that it was no joke at all. After lunch, we would be on dish wash duty, dressed in long underwear, and without glasses.

I left for a minute to go back to the room and heard Clem running toward me: “Dress up, we are leaving! The helicopter will take off within the next hour. We must go the airport right now.” Ha, ha, funny Clem, you thought I was joking with washing the dishes, and now you feel the need to make a joke too, but I ain’t a silly fool, and it’s not April 1st yet. Well, when I saw Clem dressing up, and tightening his shoes in a hurry without wasting time to comment further on his statement, let me tell you, I quickly dressed up too! I could not risk missing that flight, if it happened.

Air Greenland was able to fly us back to Kulusuk using a French-made helicopter (an Ecureuil – an Astar helicopter) flown by an Icelandic pilot. Certainly, he was used to windy conditions, and low visibility. We were reunited with Rick for lunch in Kulusuk!

We would like to thank Air Greenland for their dedication to serving our project yesterday and today. Working with us on a flexible schedule to get the cargo flight in yesterday was a big help. Accommodating us in Tasiilaq and getting us back to Kulusuk this morning allowed us to be ready for the next opportunity to fly to the ice sheet so we can begin our experiments. A continued good relationship with Air Greenland and their pilots is important for the success of our science. We view them as team members critically needed to move forward with a successful campaign.