By Alek Petty

Working on thin Arctic sea ice.

After five days of cruising through open water, it was clear we had to change course and venture further north to find ice. The satellite imagery was showing ice above 76-77 degrees North (we were around 74 degrees North), and the ice edge didn’t seem to be drifting south at any real speed. After another few days voyage northwards, we thus finally found ourselves entering the Arctic sea ice pack. This wasn’t exactly a scene from the Titanic; the transition from water to ice was a gradual one, as the ice cover evolved from millimeters or centimeters of newly forming sea ice (nilas and grease ice), to thicker, consolidated ice floes (maybe a meter or two thick; 3.3 to 6.6 feet), which caused the ship to lurch and shake as it broke its way through.

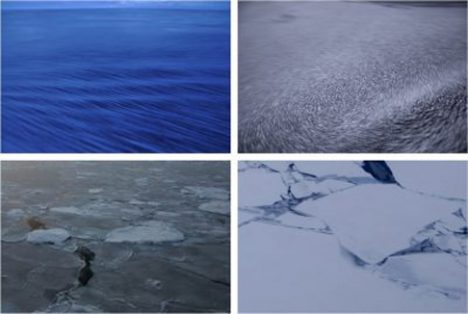

Early stages of sea ice growth: nilas (top left), pancake ice (top right), young grey-white ice (bottom left) and first-year ice (bottom right). The top photos are courtesy of Jean Mensa.

Once we were well within the ice pack, the Woods Hole team was keen to get out onto the ice and deploy some buoys. This would be my chance to get out on the ice too, as I was helping lead efforts to collect ice thickness measurements and ice cores, to better understand the characteristics (like salinity, density and age) of this year’s Beaufort Sea ice pack. The microbial and microplastic scientists were keen to join in and collect their own ice cores, too, enabling them to take a deeper look at what else might be hiding within the ice.

The Woods Hole team leader flew out with the helicopter pilot early the next morning to hunt for thick ice, and seemed to find an ice floe thick and stable enough for us to work on. I joined them on the first science flight out a few hours later to set out our survey lines and coring sites, before our cargo was carried over and the rest of the team members joined us. It was soon apparent that the ice wasn’t as thick as we had hoped.

I drilled a few quick holes and the readings all came in at around half a meter, just above what might be considered safe to work on. Our polar bear guard, Leo, wasn’t too happy with the conditions either and soon found a few good sized holes and cracks circling us. We were under strict orders not to stray from the group and to test the ice for stability as we moved ahead. I’ve previously used data from satellites, planes, and sophisticated computer simulations to estimate the thickness of Arctic sea ice. Yesterday, I estimated ice thickness by hitting it with a stick.

Danger ice!

It wasn’t quite vertical limit, and the group rebuffed my idea of roping together for dramatic effect, but there were still a few hairy moments when the odd leg found its way through the ice. Despite the added element of danger, all operations completed successfully and we hitched a lift back to the ship later that afternoon with our ice cores in tow. The Woods Hole team was working until last light to get their buoys prepped and ready to drift off through the Arctic. It was a fun, adrenaline-filled day of science, but I’d prefer it if we could find some thicker ice to work on next time around.

Tags: Arctic, Beaufort Gyre, Beaufort Sea, cryosphere, polar science, sea ice