By Eric Lindstrom

We had a whirlwind of preparations after the Labor Day Weekend. All the gear was loaded on the ship and lashed down. The scientific party (22 people) arrived and set up in various spaces around the ship. Bill Ingalls, a NASA Headquarters photographer, captured many great shots of the Knorr and the equipment. His photos are online at NASA Headquarter’s Flickr account.

SPURS researchers held a press conference the day before departing. From left to right: Eric Lindstrom, Dave Fratantoni and Ray Schmitt,

I also had the pleasure of meeting Naomi Harper, a teacher from Will Rodgers Middle School in Fair Oaks, CA. She was visiting Woods Hole and stopped by the ship. I am looking forward to interacting with her students via this blog during the voyage.

We cast off and set sail at 8:30 a.m., on Thursday, Sept. 6. While it’s a very beautiful calm day, we know that we have storms in the Atlantic between us and our destination (Hurricanes Leslie and Michael). The cruise plan is being adjusted a little so we spend the first few days focused on “outrunning” the storms. We can do out test stations and other such preparations after we have reached calmer waters west of the hurricanes. So, we are expecting rough seas at some points during the next few days and the first order of business as we set sail is to get all our gear secure on deck and in our cabins. Everything that can move needs to be secured before we face the storm waves.

[youtube dcJOl8hYJhM]

There was a nice gathering of friends and family at the wharf to see us off on our voyage. We are lucky to have such a beautiful sunny morning and calm winds for the send-off.

Thirty minutes after setting off from Woods Hole, we have our first meeting of the entire scientific party. There are people from several institutions and we all need to put names to faces. There are also scheduled safety meetings and boat drills during our first day and before we leave the calm waters of Massachusetts behind.

The only scientific work planned for the first few days, as we race past the storms, is regular sampling of surface waters to calibrate the ship’s thermosalinograph. This instrument monitors ocean temperature and salinity continuously from water coming in through a port in the ship’s hull. It will operate continuously during the voyage, but we need to collect calibration samples every 4 hours for precision salinity determination.

We are all learning about the rhythms of shipboard life. We will have people on many different watch schedules. The watches will operate on local time. That shifts as we move east across time zones. As your blogger on the SPURS cruise, I plan to float across different groups and schedules as the expedition progresses to give you multiple perspectives. On the ship, meal times are very important. We will have breakfast every day from 7:30 to 8:15 a.m., lunch from 11:30 a.m. to 12:15 p.m., and dinner from 5:00 to 5:45 p.m. I’ll let you know more about the delicacies we eat at sea!

By Eric Lindstrom

On September 6, a bunch of NASA-funded scientists, and me among them, will depart on an expedition across the North Atlantic Ocean to study salt concentration levels of seawater. But why do we want to spend six weeks at sea measuring ocean saltiness? Hopefully, over the coming months you will come to understand the motivation and get caught up in the action through this blog.

My name’s Eric Lindstrom and I am a program scientist for NASA’s Physical Oceanography program. My normal work involves developing and managing NASA’s Physical Oceanography research program. I gave up my career as a seagoing oceanographer to become a manager in our offices in Washington, D.C. However, marrying satellite observations with sea-going oceanography has been a long-term goal of NASA and that’s why I am about to go back to sea, to participate in a research project that merges both fields.

In September I’ll embark on the Research Vessel Knorr, leaving from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts toward Punta Delgada, Azores (Portugal), where we plan to arrive on October 9. This cruise is part of a multi-year research project called Salinity Processes in the Upper Ocean Regional Study (SPURS for short) and, in the U.S., it’s a collaboration of NASA’s Earth Science Division and partners funded by the National Science Foundation Division of Ocean Sciences and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

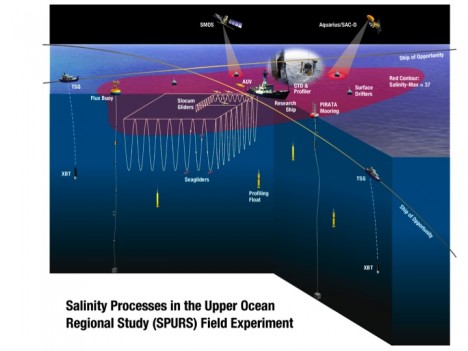

An illustration depicting the instruments SPURS will deploy in the saltiest spot of the Atlantic Ocean.

I plan, over the coming weeks, to introduce the science, the scientists and technicians headed to sea, their individual contributions to the field campaign, and the amazing technology that makes it all possible. But first you need to know some background and what to expect in future posts.

Oceanographers are keenly interested in the smallest variations of the salinity of seawater. How salty the water is from one place to another is one of several key factors in determining the density of seawater – and it’s density variations and wind what drives ocean circulation. Density is determined by the water’s temperature, salinity, and depth in the ocean. We’ll discuss the processes that change temperature and salinity in later posts (as they are at the core of the SPURS field work). In general, the effects of the sun and the atmosphere on the surface of the ocean lead to variations in the temperature and salinity that drive the ocean circulation, which in turn provides energy back to the atmosphere in the form of water vapor, impacting weather (i.e., changes in rainfall frequency and distribution) and climate. I intend to delve into many of the details of this interaction with my posts from R/V Knorr.

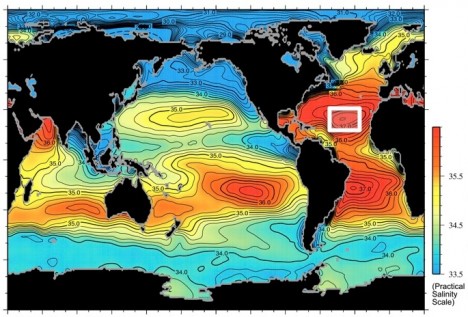

A global map of the salinity, or saltiness, of Earth’s ocean surface, showing the spot in the North Atlantic Ocean where the SPURS research cruise is headed to.

In June 2011, NASA launched a new Earth-observing instrument to measure the surface salinity of the ocean from space. The instrument, called Aquarius, is flying on the Argentine satellite SAC-D and delivers a global map of ocean surface salinity on a weekly basis. This data give unprecedented insight into the variations of the surface salinity of the ocean. While, sea surface temperature has been regularly measured from space for over 30 years, salinity has been a much more difficult measurement to make from space. The question of how do we measure salinity from space is a great subject for later in this blog – I plan on writing about it when we have a quiet day at sea!

A primary objective of SPURS is careful examination of the processes that change salinity in the upper ocean – so we can better interpret the variations in salinity seen globally from space. This year’s focus is on a high-salinity region – as is characteristic of the mid-latitude open oceans around the globe. These are relative “ocean deserts,” where there is much more evaporation than precipitation leading to saltier surface waters. In the future (circa ~2015), a second SPURS campaign hopes to examine processes in one of the “wet” sectors of the ocean, where rain far exceeds evaporation, freshening surface waters. Other processes affect salinity including advection (water circulation) and vertical mixing. I will discuss these in some detail during the cruise, because they are the subject of specialized measurements and have a big impact on our interpretation of salinity variations.

The study of salinity variations in the ocean from all the accumulated ship-board measurements of surface salinity over the last 50 years has revealed interesting trends. It turns out that the high salinity regions of the subtropics have been tending saltier and the low salinity regions of the rain belts have been tending fresher. This can be interpreted a “fingerprint” of an accelerating water cycle – something we expect in a warmer world where the atmosphere holds more water vapor. Models show that this state, roughly speaking, leads to drier dry places and wetter wet places – just what the salinity of the ocean seems to suggest. Unless there is an alternative explanation: that’s where oceanography comes in – the conclusion about the water cycle is only true if purely oceanographic explanations for the trends in surface salinity are ruled out. In other words, is there some other combination of oceanographic processes that could explain why salty places appear to be getting saltier and fresher places fresher? SPURS is ultimately about answering such questions, so we can use global salinity data and ongoing monitoring of salinity as a powerful tool in diagnosing global environmental changes.

And that’s all for today. In my next post, I’ll explain more about the scientists involved in SPURS and more about the posts you will receive from sea during September and October.