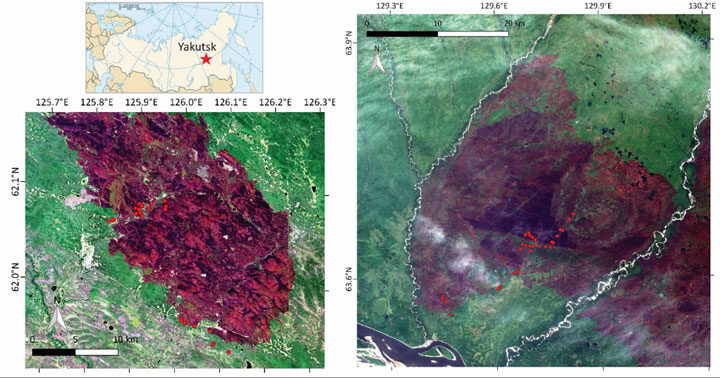

If only I could collect my thoughts about how I feel here in the tiny village of Batamay, idyllically located at the confluence of the Lena and Aldan rivers, after four weeks of campaigning in the burned larch forests of Northeast Siberia. But this process started much earlier. In December of last year we started analyzing satellite images to find suitable burn scars for carbon combustion sampling. Many people told me the idea of collecting data in Northeast Siberia is nice, theoretically, but logistically not feasible. These logistic challenges are likely part of the reason why so little data has been collected here. Yet, a data shortage in the large swaths of larch forests in Northeast Siberia is also a prime reason why we wanted to come here.

Are the logistical challenges in Siberia greater than in for example Alaska and Canada? From my experience, yes. This is mostly a matter of the difficult to travel ‘last mile’. It was surprisingly easy to reach the tiny villages of Ert and Batamay (of approximately 500 and 200 people), the small villages near our burn scars of interest. Reaching Batamay even included a scenic boat ride across the Lena river. From the villages it was about 5 km to the burn scar and 10 to 20 km to our camping sites. And this is where the adventure began. Did we get stuck in the mud? Yes, multiple times, but we made it out every time. Was it difficult to reach our sites? Yes, if often required scrambling over boggy grassland and woody debris, and through dense bush, but we always made it, and more importantly, we made it safely back to the camp. Were the stretches of camping and sampling physically challenging? Yes, we definitely felt weathered and sometimes charred, but rain or shine, we kept true to our goal of sampling more plots. And I feel proud about what we accomplished as a team! In total we measured 42 burned plots and 12 unburned plots. These plots cover gradients of forest types (larch and pine forests), fire severity and landscape position. In the fires, we collected data that will estimate carbon emissions. We also assessed how larch forests recover after fire and how the active layer, the seasonally thawed top layer of soils in permafrost regions, thickens after fire (at least before our active layer probe broke half way the campaign).

We are eager to analyze samples in the lab, and later interpret the data in our offices. We are hopeful the data we collected will improve our understanding of the role of fire in the Northeastern Siberian larch forests. We will graph our results, and write a manuscript. People will read our work, and may cite it and use our data. But we will be the only ones that know how this campaign really evolved; how we crossed rivers, woody debris and endless bush to get to these locations; how we shared our simple lunches of bread, salami, cheese, cucumber and tomatoes at some burned spot; how we were happy to finally take a serious wash in the banja, Russian sauna, when we came back in the village after days of camping. I am extremely thankful to my team for what we have accomplished. We realize that it is privilege to visit these remote places, yet this does not make the long days, difficult hikes and sometimes monotonous tasks any easier. We came from the Netherlands, USA and Russia to do this together. A big thanks to Clement, Rebecca, Dave, Tatiana, Brendan, Roman and Brian. I am also very grateful to our local collaborator Dr. Trofim Maximov from the Institute of Biological Problems of the Cryolithozone of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Without Trofim and his team, none of this would have been possible. I was also touched by the welcoming and warm-hearted locals from our host villages. They were very curious to our endeavors, and even though language barriers inhibited our conversations, they also helped making our campaign a success.

We sampled burn scars from 2017 and 2018. This year’s fire season in Siberia is extremely vigorous. Many days we experienced smoky skies partly veiling sunlight; a direct consequence of fires burning nearby. This year’s events also demonstrate the urgency of why we need to better understand the interaction between climate change and fires in Siberia. As our field campaign developed this year, we started talking more and more about next year’s campaign. We are intrigued by the current fires within the Arctic Circle in Northeast Siberia. We want to understand their climatic drivers and consequences. We will be back next year for Fire Expedition Siberia 2020.

This field campaign is part of the ‘Fires pushing trees North’ project funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and affiliated with NASA ABoVE. This blog post was written by Sander Veraverbeke, assistant professor in remote sensing at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, and project lead of ‘Fires pushing trees North.’

DBH (diameter at breast height)… 3.7 cm, killed by fire, severity 2, … adventitious roots at 7 cm (adventitious roots are small additional roots that larch trees have that help determine the depth of burning in the organic soil layer). Those are the words that would repeatedly disturb the forests’ eternal silence, besides the occasional call of a black woodpecker. This routine is part of making an inventory of the many trees (varying from roughly 50 to more than 300) that cover the 30 meter by 2 meter transect that is laid out in the field plot of interest. Such a transect is selected based on homogeneity in fire effects and assumed to represent a larger area of 30 by 30 meters, the size of a Landsat satellite pixel. This enables the direct comparison of ground s and satellite observations, which is in turn essential for upscaling to regional or continental scale estimates of available biomass and combustion.

Our science team is in Batamay now, a small village about 170 km North of the capital of Yakutia and the coldest city on Earth, Yakutsk. Compared to our previous location, Ert, this is farther away from the main cluster of large fires that plague Siberia right now. However, fires are also active here, as I witnessed during my flight from Amsterdam to Yakutsk.

In order to get to Batamay, we had to drive for multiple hours and cross the Lena river by boat. The boat trip was not exactly like the luxury Lena river cruise that can be booked to visit the well-known ‘Lena pillars’, but it brought us to our study destination. After reaching Batamay, we continued our travels using one of these typical sturdy Russian vans to the designated camp site for a week of camping inside the burn scar that we wanted to measure. This burn scar is the result of a particularly high severity fire from 2017. The current science indicates that fires in Siberia are mostly low severity surface fires compared to the high severity crown fires in boreal North America. The high severity core of the Batamay burn scar may be out of the ordinary and attracted our interest. Could Siberian fires locally be more severe than thought and do we underestimate their emissions? Furthermore, what does this potential of high severity fire in Siberia mean for the future fire regime in a changing climate?

On the way from Yakutsk to the burn scar we have had some fine demonstrations of the Yakutian approach to problem solving. Little time is spent on overthinking possible issues beforehand, and instead problems are solved on the spot. Surprisingly, this method has been successful in every occasion we experienced an obstacle. For example, when a stretch of water is too shallow for a boat to float or a road too muddy for a car to cross, the consequences are faced instead of avoided, but always solved afterwards. This radiates a certain simplicity and relaxed approach to life that is almost fully opposed to the scientific approach and might be hard to relate to as westerners. What do the locals actually think of our complicated scientific instruments and methodologies? Sadly this is hard to say, because of the locals’ Yakutian language which is closer to Turkish than Russian (as if Russian wasn’t hard enough already) and introduces multiple new letters to the Cyrillic alphabet. And also because the locals are not men of many words anyway. However, like everyone else, these people also notice the effects of climate change, such as warmer winters and more heavy rain spells, such as the recent floods near Irkutsk

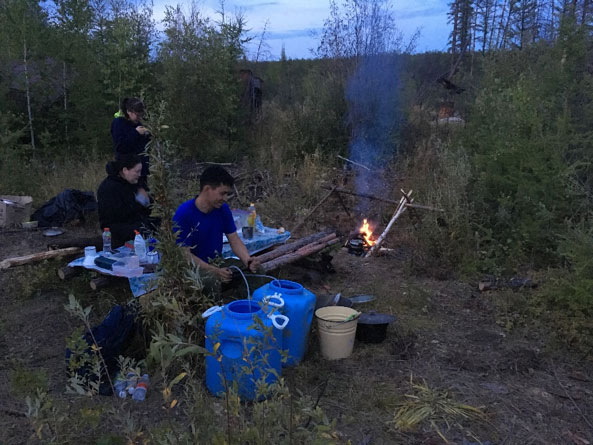

At the camp site, we were accompanied by five locals from Batamay: a guard, a driver, two cooks, and a guard dog. It was comforting to have this company and it is safe to say that this made all of us sleep better at night. In a matter of minutes a patch of tall grass was transformed into a cosy camp site including a fire place, picnic table and food warehouse, all made from the branches and logs available in the forest, and some old containers used previously by road constructors. Another great example of what you can construct from logs: a trailer able to withstand all bumps we faced on the road.

During our camping stay in the Batamay burn scar we have collected data from 24 field plots with varying degrees of fire severity. The coming week we will stay in a house in village and we will venture out in the fire scar again. Now we will focus more on unburned ‘control’ plots. This allows the comparison of the situation before and after the fire, which gives invaluable insight in quantifying the greenhouse gas emissions from the fire.

This field campaign is part of the ‘Fires pushing trees North’ project funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and affiliated with NASA ABoVE. This blog post was written by Dave van Wees, PhD student at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, studying global fire emissions using satellite data and biogeochemical modeling.

After the Tomsk campaign, we traveled to Yakutsk for the next leg of the campaign that came with new scientific objectives. Our team now included three members from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, two members from Woods Hole Research Center and one collaborator from the Institute of Biological Problems of the Cryolithic Zone from the Russian Academy of Sciences. Our destination was a burn scar from last year’s fire season near the small village of Yert, approximately 200 km West of Yakutsk and surrounded by larch forests, sometimes mixed with pine forests, growing on permafrost terrain. Approximately 20% of the boreal biome are dominated by deciduous larch forests, yet we do not really know how wildfires influence carbon stocks of these ecosystems. We aimed to fill parts of these knowledge and data gaps by collecting ground measurements to quantify the amount of carbon released during these fire events. This is also a formidable opportunity to see on site what these forests look like before studying it at larger scales from satellite data.

Our first task was to reach our camping site located within the burn scar of approximately 900 km2. On our way to the field site our local collaborator and driver showed us how the forests are honored in Yakutian culture. We made several stops along the road to worship the Bayanay spirit, the spirit of hunting, taiga, and its animals and birds, by leaving several presents on trees. Our local collaborators told us that these offers would bring good luck to our field campaign. Thus, of course we were very generous.

We had been told that locals from Yert were quite excited that an international team would visit their village. Indeed, when our team arrived at the village after a five-hour drive from Yakutsk we were kindly welcomed by the chief of the village with a cup of kumiz, local drink of fermented horse milk, and several local dishes. While having tea we talked more about the scientific goals of our campaign, and the local surroundings. They were also intrigued about the fact that our ‘Dutch’ team consisted of team members of French, German, Belgian, American and Russian nationalities. When we selected this little village as our access point to access the burn scar several months ago several thousand kilometres from here, in Amsterdam, using road maps and satellite images, we had no idea that this local community would be so welcoming and honored by our visit.

The first five days we sampled burned plots with gradients in fire severity, soil characteristics and vegetation composition. In each plot, we performed a wide range of measurement including soil sampling for carbon analysis, aboveground biomass and combustion estimates, active layer thickness measurements, tree cores for stand age estimates and post-fire tree seedling counts. Getting into these plots in such a remote area was quite challenging as we had to hike in dense bushes or waterlogged grasslands carrying all the equipment and freshly collected samples, and some days were unfortunately rainy. With these wet and cold conditions, the camp fire became an important place after the working days to dry clothes, but also to keep positive minds sharing tea and snacks together. It was worth facing these tough conditions as we made some interesting and unexpected observations. For example, we did not expect to find relatively young, approximately 50 to 60 years old stands, that were very dense and burned with high severity.

Waking up with rain showers in the morning of the fifth day of the campaign, we decided in a hurry to return to the village one day earlier than originally planned. More than working under rainy conditions, we were worried about the road that could become too muddy, even for our sturdy all-terrain van. We got indeed stuck multiple times on the muddy road back to the village, but thanks to a collective ‘pushing’ effort of the team and particularly to the amazing skills of our driver and ‘hero’ Dima, we safely made it out through 15 kilometres to the village after four hours on a muddy forest road. And this was supposed to be our rest day!

The work in the second week around this burn scar aimed at finding and sampling unburned sites along a forest road. These unburned plots were selected as ‘best’ matches of our burned plots by having similar forest compositions and landscape positions. The measurements in these ’control’ plots will allow us to estimate pre-fire carbon stocks, and thus act as a reference for comparison with our burned sites. While the comfort of staying in the village and sampling along the road may sound easier than our earlier camping experience, we ran into several unexpected mishaps. Our van suddenly broke down on a seemingly ‘easy’ part of forest road, and one team member had to recover from a muscle strain for two days. We quickly learned making a plan B… or even plan C. Luckily, we could rely on our local collaborator and driver, which were of a tremendous help throughout the campaign in addition to taking care of most of the logistics. They were very helpful in sharing knowledge on the ecosystems, but also cooked delicious meals. The jury is still out whether Dima’s soup or Roman’s pasta was the best meal.

We collected data in 24 sites which will enable us to better understand carbon emissions from fires in these larch ecosystems. This dataset will be completed with similar measurements that we will make in another burn scar on the opposite side of the Lena river North of Yakutsk in the upcoming ten days.

This field campaign is part of the ‘Fires pushing trees North’ project funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and affiliated with NASA ABoVE.

This blog post was written by Clement Delcourt, PhD student at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, researching carbon emissions from boreal fires.

2019 is bound to become one of the largest fire years on record in the Arctic Circle, and especially in Siberia. How much carbon these fires release remains a challenging question. Very little ground data on fire emissions is available for Siberia and estimations are difficult since the main part of the emissions originates from organic soils, which is harder to retrieve from satellite imagery than emissions from aboveground biomass. Our research team from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (the Netherlands), Woods Hole Research Center, Northern Arizona University (USA), Pyrenean Institute of Ecology (Spain), and the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences and Tomsk State University (Russia) are joining forces to better understand fire dynamics in Siberia.

After an adventurous three-hour drive, our field crew gathered with the local collaborators at Kajbasovo Research Station near Tomsk, in Russia. We aimed at finding old pine trees in burned and unburned sites, which we then core with tree borers to build tree-ring chronologies. Wildfires in this western part of the Siberian boreal forest usually don’t burn with high intensity allowing some resilient trees to survive multiple fire cycles. Thus, we aimed at using the chronologies to reconstruct the fire history of the area and to assess the response and recovery times of the ecosystem after fire events and other disturbances.

Little did we know that we would ourselves witness the severity of this year’s fire season. Except for the first day, we did not see a clear sky. From then on, the sun would only appear as a bright orange or blood red ball behind lots of smoke originating from wildfires in the Krasnoyarsk region hundreds of kilometers away. One good thing about this is that it dampened the heat, since we were already quite warmly dressed in our tick- and mosquito-proof clothing.

Mosquitoes and heat, however, were only small obstacles, as we set out with our borers to find trees older than 100 years. We really wanted trees from that age so that we can build sufficiently long chronologies. Even at the most remote places we were surprised to often see signs of human activity such as past logging, resin extraction or littering. One day we even saved a duckling out of a fisher net set up a good 4 hours bumpy drive away from the next village. Or sometimes we would simply not find old trees because of natural disturbances or growth restrictions. Eventually, we did manage to sample 12 sites with old trees with different fire severities and hydrologic characteristics. These will now be analysed further in the lab to extract and crossdate the tree rings.

Being in the field and having only very little time to sample can be an intense working experience, but there were many special little moments too. Our driver overcame every obstacle on the way to bring us to very remote places, and our cook took great care of us with plenty of delicious borscht, buckwheat and blinis (type of pancakes) and provided large amounts of water and kompot (sweet fruit beverage). And our evenings were spent at camp fires diving into local culture and connecting the people.

After ten exciting days in Tomsk we are now resting and recovering in Yakutsk for the weekend. We are using the time for some team building activities, and we are enjoying some solid hours of sleep. We went shopping for supplies for the second part of our field campaign, which will lead us to even more remote areas around the little villages of Ert and Batamay in the next four weeks. There, we will visit recently burned forests and measure the carbon losses due to fire events. In addition, we will take more tree chronologies to estimate the stand age, and count seedlings to see how forests recover after fires of different severities.

This field campaign is part of the ‘Fires pushing trees North’ project funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and affiliated with NASA ABoVE. The Tomsk part of the campaign was funded by INTERACT.

This blog post was written by Rebecca Scholten, PhD student at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, researching arctic-boreal fire dynamics.

By Eric Lindstrom

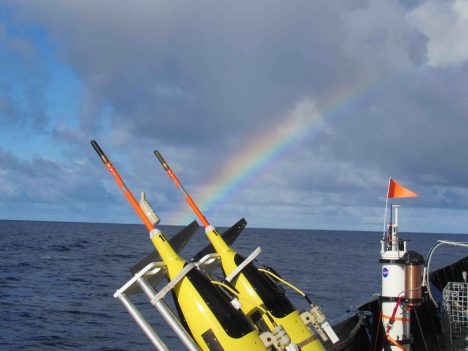

Instruments ready for Lagrangian array deployment at the end of the rainbow.

What do Leonhard Euler (1707-1783) and Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1736-1813) have to do with SPURS-2? How do we have two experiments going on simultaneously honoring the work of these famous mathematicians?

Two frames of reference have taken their names from these 18th century mathematicians. In science, including oceanography, when we make measurements of fluid flows fixed in space, we watch properties such as temperature or salinity as currents carry them by our instruments. This is called an Eulerian frame of reference. However, sometimes we make measurements while following the flow, trying to tag a parcel of water and watch as it moves and changes over time. This water following perspective is called the Lagrangian frame of reference. For example if you watch a river flow past from the bank, you are using an Eulerian frame of reference. If you examine the river from a boat flowing with river, you would be making a Lagrangian observation of the river.

In SPURS-2 we use moorings and a fixed grid of stations to describe a patch of ocean as the water passes by. Moorings, stations, and satellites provide the Eulerian perspective over the year of SPURS-2. We use a variety of drifters, autonomous vehicles, and profilers (instruments embedded in the moving water parcels) to also build an extensive Lagrangian view of the ocean over the year. We use the Lady Amber over the course of the year to service and reset some of the Lagrangian experiment as those assets drift away from the study site. We use the Revelle to deploy the Eulerian array and to seed the ocean with the Lagrangian instruments to be tended at later times by Lady Amber. It really is two experiments united to understand the salinity patterns and movement of freshwater in the ocean!

Audrey Hasson driving the A-frame during mooring deployment.

During the Revelle voyage we are also planning a short-term (48-72 hour) Lagrangian experiment capture the processes by which rainwater mixes into the ocean. We will launch drifters specially designed to follow the surface current during a rain event and then follow them for day or two. We will sample the region around the drifters using the Revelle to further examine the changing temperature and salinity properties of the upper ocean. The Revelle will attempt to take several snapshots of the ocean conditions as the Lagrangian array disperses over a day.

Together our Lagrangian and Eulerian sensor arrays constitute a sensor web in the ocean. This sensor web captures ocean motion and salinity changes (particularly) on a wide range of time and space scales. This allows us to analyze processes that lead to changing surface salinity all the way from minutes to seasons and from millimeter size turbulence to major ocean currents. We cannot measure all things we would like all the time and in every place, so we have tuned our effort and sensor web design to provide enough information to estimate what we would like to know. We would like to know about the role of turbulent mixing at the surface; we would like to know the role of eddies in transport of freshwater; and we would like to know how the major equatorial currents impact the eastern tropical Pacific low salinity pool. Obtaining such knowledge of the ocean is ambitious and challenging. SPURS-2 is giving us a shot at providing some unprecedented new knowledge.

Andy Jessup, Chief Scientist on SPURS-2 R/V Revelle.

I would like to give a shout out to our chief scientist on the voyage, Andy Jessup, from the University of Washington Applied Physics Laboratory. Andy has demonstrated extreme patience and diligence to his duty to represent the many investigators working on diverse problems and scales in SPURS-2. He has a team from APL aboard with a complex set of measurements to execute. He balances the time devoted to his own science project and his duties as leader of all the projects represented on the ship. That is not easy and he has found a way to give everyone a voice.

I hope to devote some upcoming blog time to our able CTD crew from Scripps led by Janet Sprintall, the ocean currents in our region in general, and the interaction with the teams back home as seen through the eyes of Audrey Hasson.

Please feel free to send questions and comments on the blog. I’ll do my best to answer all fair questions!