March 17, 2011

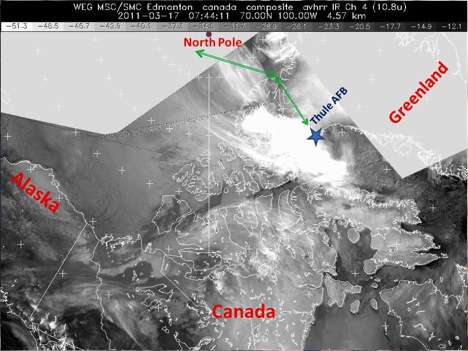

Another early morning wake up, with a quick check of the weather. I went to bed last night with snow falling, and not so promising satellite pictures showing a fairly significant storm system off to our west. I was thinking that we would be cancelled due to weather, but woke up to surprisingly calm conditions. The system skirted by us to our west and headed due south rather than east. The weather conditions here in the Arctic are much different from home, and I am still trying to figure out how the weather systems move about the area. I created a picture from this morning’s satellite image, with approximate locations of Thule, and our proposed flight path. You can see the major part of the weather was to our west, and we had some high clouds in our operating area to the north towards the pole.

IR Satellite Image from 0444 local. Large area of cloudiness to west of Thule, but cleared out by our departure at 0815 local. Area of high clouds near the flight path in vicinity of North Pole, that we went down to 1,000 feet to get under. Imagery is courtesy of Environment Canada

Today’s mission was another satellite underpass track, this time for the European Space Agency CRYOSAT platform. Take off was under relatively clear skies, and we got some great views of the surrounding mountains and glaciers around Thule. I am told that this was nothing compared to the upcoming land ice flights, but I was still in awe with the beauty of the ice flowing towards the sea, and the morning sunrise reflecting off the snow covered mountains. The calving front was clearly visible from our low altitude just after take-off. This is the area were the land ice meets the water, and at this time of year the water is still froze, so the sea ice sort of acts like a buffer to hold up the glacier. During the summer months, the sea ice retreats due to the warmer air temperatures, and the glacier flows freely into the water, and calves into icebergs.

Calving front of a glacier around Thule, Greenland. Credit: LCDR Woods

About an hour and half into our flight, we reached the beginning of the data collection line. We dropped down to 1500 feet in attempt to get under the clouds to allow the instruments on board to collect data. Today, the cloud deck was down around 1,000 feet, so we had to fly below that level. This made for some spectacular viewing of the sea ice conditions.

LCDR John Woods and MIDN 1/C Eric Brugler, observing sea ice conditions in the Arctic Ocean. Credit: Jim Yungel

After about 2 hours of flying our survey line, we had reached approximately 87.5 degrees north, only 150 miles from the North Pole. The P-3 made a wide S turn to back track on the same line that we covered on the way out. This gives the instrument teams, twice the data to be compared to the satellite that would be passing over our heads, taking similar measurements. Another 2 hours of data collection on the way back, and now we have just broken off the survey line and are heading back to base.

Happy St. Patrick’s Day everyone! I have yet to see a single sign on base advertising any sort of celebration, so we might just have to create our own. Midshipman Brugler departs tomorrow morning on the rotator flight back to BWI airport, so we will go out in search of some congratulatory Corned Beef in honor of his departure. I will be staying on here in Thule for at least one more week, hoping to get on the flight across the Arctic to Fairbanks, Alaska to survey the Navy Ice Camp. Weather permitting of course!

March 16, 2011

Today was the day I had been waiting for all week. It was the first flight day of the IceBridge operation out of Thule, Greenland. Flying today had a special meaning to me for a few different reasons. I recently was selected to become a Navy pilot, which is a goal I have been working towards for some time. Therefore, upon completion of graduate school, I will report to Pensacola Florida and begin flight training. I was able to talk to the pilots, flight engineers and air crewmen of the NASA P-3B who happen mostly ex-Navy guys which was a pretty cool experience for me. So not only was I constantly interacting with the scientists and engineers, but with the people actually flying the aircraft and allowing the mission to happen in the first place.

The day started early because we had to report to the aircraft by 0700, so I woke up got breakfast and headed right over to the hanger.

This is a picture of me in my flight suit and flight jacket getting ready to board the aircraft early in the morning. Credit: LCDR John Woods

The actual flight, although a long mission, was nothing short of amazing. We flew a path known as “Connor Corridor,” a flight taking us from Thule to north of the Canadian Archipelago.

This was a “ENVISAT” mission meaning we would be flying over the sea ice and actually going over a region that an ESA ENVISAT satellite would look at later in the day.

This was really interesting for me since I am studying the sea ice variation in the Arctic; therefore it was cool getting to see firsthand what I am reading about in books and learning about in my classes.

This is a picture taken looking out the window of the P-3B as we flew at 1500 feet. It was very cool getting to see open leads and ridges as the picture shows. This appears to be multi-year ice because the ridges seen in the picture are weathered indicating that they have been there for multiple years. Credit: LCDR John Woods

Not only did I get to see some amazing scenery, I also learned a lot from the people taking measurements onboard. On the P-3B, there is a gravimeter, a few airborne topographic mappers (ATMs), some cameras for the digital mapping system (DMS), ku-band radar, snow radars, MCoRDS radars and a magnetometer. All of this equipment is collecting data and in fact a lot of the instruments’ measurements are used together with other equipment in order to give the most accurate depiction of the Arctic as possible.

We landed around 1600, making it about an 8-hour mission! Although it was long, it was an experience I will remember for a lifetime; I am excited to fly again tomorrow, hopefully the weather will hold out and let us get in the air once again.

March 16, 2011

My alarm clock was set for 5:30 this morning to wake up, shower, get some breakfast and be at the hanger no later than 7 a.m. for an 8 a.m. take off. The weather was good for our target area north of the Canadian archipelago (islands), to survey the sea ice beneath the ENVISAT (LINK) satellite overpass that would take place later on in the afternoon. Part of the goal of IceBridge is to compare measurements taken on the P-3 to those measured by the satellites orbiting overhead. Since the satellite has much better spatial coverage then our airplane, if we can get good agreement between its data and the P-3 data, then we can trust that the satellite data is good. This will be tested on another level later in the week (hopefully) when we fly over the Navy Ice Camp, north of Alaska, where they will have instruments on the ground that we will then compare both our plane and satellite data again.

What type of instruments do we have on the NASA P-3? A Laser altimeter called ATM (Airborne Topographic Mapper), measures the distance between the plane and the sea ice surface, which gives us an elevation measurement. There are multiple radars, including one that measures snow thickness on the surface of the ice. A gravimeter is measuring Earth’s gravitational field, which in turn tells us about the bathymetry, or sea floor below. A magnetometer is measuring changes in the Earth’s magnetic field, again to give us an idea as to what the sea floor below looks like. We also have three digital cameras pointed downward below the plane taking constant pictures of our flight path.

Ariborne Topographic Mapper (ATM) with Jim Yungel, ATM Program Manager (center) and Michael Studinger, project scientist for Operation IceBridge (right). Credit: LCDR Woods

It took about 90 minutes to get to our first collection waypoint. Weather plays an important role for the data collection because clear skies are needed for the instruments to take proper measurements. This morning’s weather briefing looked like our collection area was going to be relatively cloud free. After the transit, we dropped down to 1,500 feet and switched all the instruments into collect mode. The weather was perfect, and viewing the sea ice out the window was breathtaking. Lots of people think of the Arctic as just a flat expanse of white. This couldn’t be further from the truth. There are all sorts of cracks (leads) and mountains (ridges), similar to tectonic plates. The ice below is constantly moving via the winds and currents, and those forces acting on each piece of ice makes for a very dramatic seascape. There are areas of open water, though only for a few hours, because the surface temperatures below are well below freezing (approximately minus 20 degrees Celsius). You can see varying stages of sea ice formation, where there used to be open water, and the re-freezing process has already begun. It was rewarding to talk trough the different ice types with Midshipman Brugler, who took the Polar Science course last year, and get visual confirmation on concepts we discussed in the classroom.

The sunrise as seen from about 1,500 feet over the frozen Arctic Ocean. Credit: LCDR Woods)

Cracks (leads) and ridges are visible in the sea ice. Credit: LCDR Woods

After approximately 2 hours of data collection at 1,500 feet, we turned the P-3 around and climbed to 17,000 feet. We collected data on the exact same track as our outbound leg, testing the instruments between low-level and high-level collection. The sea ice took on a much different perspective at this higher altitude. We could see individual features before such as actual blocks of ice piled up on each other at a ridge, but now we saw a much larger area, with decreased details. The ice still does not look flat, but more like a jagged jigsaw puzzle, with intermittent breaks in the ice. Both legs were equally exciting and I am looking forward to being back in the air again tomorrow … weather permitting!

March 14, 2011

Today was busy day; a cargo shipment arrived with some instruments for the ground stations at 1430, and the P-3 arrived from Wallops Island, Va., at 1535. The air temperatures were about 20 below zero, with wind chills around minus 30 degrees Celsius. I was able to get right outside the hanger, and actually shot some video and photos of the P-3 landing, from atop the taxi way stair truck. It was a bit hazy, with some blowing snow, so visibility was not the best, but I was able to snap some decent shots which would prove helpful later without knowing it at the time.

After transiting from Wallops Island, Va., the P-3 lands in Thule, Greenland. Credit: LCDR John Woods

The P-3 seemed to land very nicely from my vantage point across the runway, and it proceeded to taxi around towards the hanger. When it was about a hundred yards away we noticed that there was something wrong with the front tire. It had blown out during the landing/taxi. Later the pilots would use my photos of the plane landing to verify that the wheel had proper alignment during final approach. Unfortunately, due to the repairs, we will not be able to fly our first mission until Wednesday, March 16, however, the instrument teams will be able to utilize this time to finalize ground station set ups and calibrations. Hopeful for a sea ice flight on Wednesday!!

The P-3’s front tires blew out upon landing/taxi in Thule, Greenland. Credit: LCDR John Woods

March 11, 2011

Eric Brugler is First Class Midshipmen who is an honors Oceanography major at the United States Naval Academy. He is interested in the polar regions of Earth because he believes they play a very important role to the Earth’s climate system.

My research is focused primarily on sea ice and using airborne measurements to infer sea ice thickness over an area of the Arctic. If only the person sitting in the window seat knew that, maybe he would have understood why I kept leaning over him to get a look out the window.

Stepping off the plane was a shock in itself, all the moisture in my nose immediately froze! The highlight of my first day was definitely getting my “Arctic gear;” so now when I walk to the chow hall, at least I won’t be shivering the whole way. In all seriousness, the gear they issue to us upon arrival is really a lifesaver; the temperatures get to 50 below zero on some days. Having this gear will make the stay much more comfortable.

Our first flight in the P-3B aircraft, NASA’s scientific data collecting plane, won’t happen before Tuesday [March 15], so everyone is anxiously awaiting to finally get airborne and look at areas in the Arctic that are changing quite rapidly. Understanding the change happening in the Arctic is very important because the poles serve as harbingers for the Earth’s climate system. Basically this means that the poles give insight into what changes will happen around the world before any other place on earth. Being able to come to the Arctic and study this first hand is quite humbling since I am only a senior in college. However, I think that having firsthand experience will enhance my future studies as I continue to delve further into polar science.