Floe | flō | n. A sheet of floating ice.

Central to the entire MOSAiC Expedition is the MOSAiC Floe: a large sheet of sea ice that was carefully selected back in October as the ideal place to anchor Polarstern for an entire year. It was chosen due to its size, structure (a mix of thick multiyear sea ice and thinner first year sea ice), and forecasted drift trajectory. Over the past five months, it has become a second home for many scientists. Here’s a brief tour of our workplace:

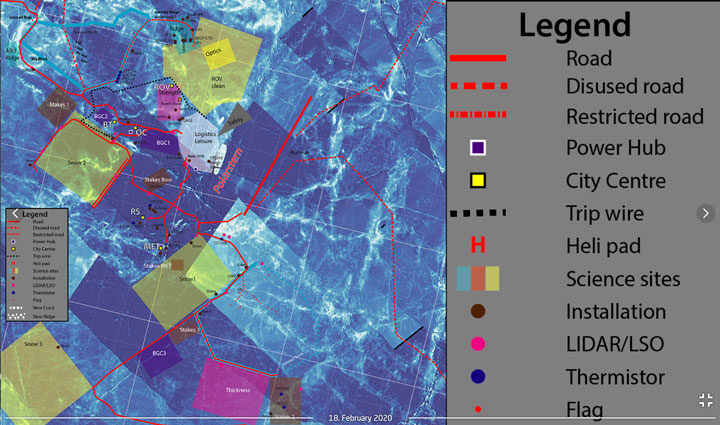

The Central Observatory (CO):

Nearest to Polarstern, the CO is the primary place where measurements are taken, both from continuously operating instruments and from sampling trips off of Polarstern. It houses many installations, from small stakes just a few inches tall, to larger huts and tents that can comfortably fit a few people inside, to 25-meter-tall towers with dozens of instruments installed. Most installations are grouped into ‘cities’ by scientific discipline. There is MET (meteorology) City, Ocean City, Balloon Town (for weather balloons – not clowns), the Remote Sensing Site, and the ROV (Remote Operated Vehicle) Site, to name a few. There are also clean areas dedicated to the sampling of snow, measuring ice strength, and studying biogeochemical processes.

Throughout the CO, there are carefully placed roads that lead from Polarstern through the Logistics area (where snowmobiles and other gear are parked) and to the different cities. Perhaps most importantly, there is also a ‘trip wire’ alarm around the CO that is able to send up a signal flare if a polar bear walks into it, providing an additional safety measure when out on the ice.

Area II:

Outside of the CO is known as Area II. This mainly houses the “Dark Site” – a place where sea ice cores are taken each week. The Dark Site consists of two different locations from which cores are drilled: a first year ice site and a second year ice site. This area is located far from the lights of Polarstern and kept as dark as possible, so as not to disturb some of the ecological work that is going on. During the winter darkness, anyone visiting the Dark Site had to use a red headlamp, which has been proven to have the least impact on the organisms living below the ice. Due to the distance away from the CO and Polarstern, visiting Area II requires additional preparation and safety gear. My main task on MOSAiC is drilling sea ice cores, so I will venture to Area II at least once per week during leg 3.

The Distributed Network (DN):

Furthest from Polarstern is the Distributed Network, which is home to exclusively autonomous instrumentation. The DN sites are not part of the MOSAiC Floe, but instead range from around 5 kilometers to over 30 kilometers away from Polarstern. Almost all sites require a helicopter to visit, an usually these visits consist of fixing broken instruments or changing batteries. The purpose of the DN is to have measurements far from Polarstern, in order to determine the representativeness of the MOSAiC floe with respect to the ice in the rest of the Central Arctic.

Together, these areas make up the field sites of MOSAiC. It’s a pretty cool place to work!

The MOSAiC Leg 3 team is officially on board Polarstern, and science activities have quickly begun.

The first few days on board were filled with handover activities from the previous leg of the expedition. Leg 3 scientists met with members from leg 2 to get a general introduction to the instruments, experiments, and life on the MOSAiC ice floe. Given that leg 2 was on Polarstern since late December, they truly are experts in the scientific activities occurring out on the ice.

During the handover, I met with members of the leg 2 ice team and visited different sites around the floe where most of my work will take place. Since it is my first time on Polarstern, I was also shown where different labs and workspaces are located, where to find tools and instruments to take out into the field, and, perhaps most importantly, where the coffee machine is! These days were invaluable for preparing the leg 3 members for work, and even more important to ensure that MOSAiC continues to run smoothly with a new team at the helm.

After the handover, it was time to say farewell to leg 2. We sent them off in true ‘Arctic expedition’ style with a gathering out on the sea ice between the two ships. All members from the science teams as well as the crews from both the Polarstern and the Kapitan Dranitsyn were invited for bonfires, hot tea, and group photos. The next morning, Kapitan Dranitsyn left on its return voyage to Tromsø, and leg 3 was left alone on Polarstern.

It didn’t take long for us to get started. The morning of the Dranitsyn departure, some teams already set out onto the ice to take measurements. I was working with another member of the ice team to construct a radiation station that we deployed on the ice a few days later. This type of station holds a few instruments that detect the amount of solar radiation both above and below the sea ice. It was necessary to deploy these instruments early in the leg, so that they would be operational for the first sunrise of the year. So far, we have been in a state of constant twilight – a red-orange sky for most of the day. In a few days, the sun will rise above the horizon for the first time in 2020. With this new station, we will now be able to measure the amount of solar energy that reaches (and penetrates through) the sea ice.

It has been extremely busy since leg 2 departed, but everyone is excited to be working on the ice. Here’s to a successful leg 3!

After about 28 days on board the icebreaker Kapitan Dranitsyn, our Leg 3 team has arrived to the the Research Vessel Polarstern! We are currently at 88.3 degrees N and 31.3 degrees E, less than 120 miles from the North Pole.

The roughly four-week transit cruise started slowly, as we were anchored in the fjord outside of Tromsø for six days. Storms in the Barents Sea led to waves around 5-6 meters (and sometimes as high as 12 meters) tall, and the ship’s captain made the decision to wait out the storm in the safety of the fjord. Once the storm passed, we sailed in open water for two days before entering the sea ice pack.

I have spent the last few years of my life studying sea ice from above –mainly using satellite and aircraft-based data. Getting to see the sea ice with my own eyes was an entirely new and extremely gratifying experience. Immediately clear was the abundance of unique features and small-scale complexities in the sea ice cover that are not easily resolved from satellite data. When viewed from hundreds of kilometers away, the sea ice often appears uniform and relatively simple. When on a ship just a few meters from the ice itself, however, one can see just how dynamic and variable (and beautiful!) the ice cover can be.

Once in the sea ice pack, our ship, the Kapitan Dranitsyn, had the arduous task of breaking through the ice to reach Polarstern. Most icebreakers only operate from spring to autumn, when the ice is thinner and can be more easily broken. We, however, were traveling very far north in the heart of winter – something that is seldom attempted due to the frigid weather conditions and thickness of the sea ice. We moved slowly at times, but eventually made our way to Polarstern. According to the Alfred Wegener Institute, the head organization of MOSAiC, this was the first time that a ship has made it this far north under its own power so early in the year, which is a new record in the history of polar research. It was truly an impressive feat, and we are all grateful for the Dranitsyn crew members who made it possible!

Given the difficulty of the mission to reach Polarstern, our transit time ended up being longer than expected. Instead of the planned two to three weeks, it took us a little over four weeks to reach our destination. While this was a long time to spend on a ship, it was invaluable for getting to know our fellow teammates, planning our tasks and experiments that we will begin when we reach the MOSAiC floe, and learning about everyone’s scientific plans for the expedition. We have been keeping quite busy, often with more than four meetings or seminars each day. Outside of our work, we spend time at the gym, have trivia and karaoke nights, and play card games. There was even a ship-wide ping pong tournament!

Now that we have arrived, we will begin our handover activities. This means that we will work closely with members of the Leg 2 team on board MOSAiC to learn our measurement procedures and responsibilities on board Polarstern. After a few days of handover, the Leg 2 team will depart for home on Dranitsyn, and we will be left on board Polarstern to officially commence Leg 3 of MOSAiC.

Now the real work begins!

Greetings from Tromsø, Norway!

A few months ago, we heard from Nathan Kurtz about his experiences on board the German icebreaker Polarstern during leg 1 of the MOSAiC expedition. MOSAiC is now in full swing, having been frozen into the Arctic sea ice pack for roughly 3 months.

My name is Steven Fons, and I’m a doctoral candidate at the University of Maryland and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. I am here in Tromsø preparing to join MOSAiC for leg three of the six-leg expedition. We will leave port tomorrow on the Kapitan Dranitsyn, and sail for roughly two weeks before reaching the Polarstern.Though all of us participating in leg three are in our final preparations before departure, my preparations began many months ago with various required training courses. Having never participated in a field experiment of this scale, it was necessary (and very helpful!) to learn as much as possible before heading out on the ship. The first trainings were Arctic Field Safety and Polar Bear Safety courses, which took place in Denver, Colorado. Here, we learned what gear to bring, how to prevent and deal with hypothermia, and how to spot – and stay clear of – polar bears.

Another required training was a U.S. Coast Guard-approved STCW (Standards of Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping for seafarers) class, which is a multi-day course where we learn all about safety aboard a ship. Components included first-aid, sea rescue, and even basic firefighting.

Finally, I made a trip up to Fairbanks, Alaska, to learn how to take measurements required for the MOSAiC Expedition. I focused on taking sea ice cores and sea ice thickness measurements, which is what my main task will be once aboard Polarstern. Temperatures got down to -30 ° F, which was great preparation for being on the sea ice!

Here in Tromsø, all participants of leg three met in person for the first time, to go over the last bits of information before departing. We collected our polar clothing, discussed the logistics of the expedition, and had even more safety training. One of these trainings involved learning what to do if someone fell into the water. To simulate that situation, each of us donned safety suits and jumped into the icy fjord!

All of us here are excited to get out on our transit vessel and make our way towards the sea ice. It sure is tough to leave this view of Tromsø, but I can’t wait to put all this training to good use.

Ten days ago the Polarstern set sail from Tromsø, traversing the remote Kara and Barents Seas and crossing just north of the islands of Novaya Zemlya and Severnaya Zemlya. These days in the ice-free seas were filled with preparation work such as moving cargo for staging on the ice, readying equipment, discussing work plans, and perhaps most importantly: getting to know all the people I now live and work with quite closely every day. Much like the ups and downs of the waves in the ocean, the journey has had its share of each. The low point most surely being a few days of sea sickness which was quite debilitating, though not actually as bad as I had feared before the trip.

We entered the Arctic sea ice pack a bit east of Severnaya Zemlya in search of seismic instruments deployed a year ago on the ocean floor. The ship’s feed of satellite data told us the concentration of ice in the area and as we drew near the ship came alive with excitement as people gathered to see the first ice of the expedition. The ice that we saw was at first just a few scattered floes, mainly ice that had barely survived the summer melting season. But this gave way to areas filled with second year ice covered with snow and a dazzling array of beautiful ice types that represent the early stages of new ice growth. Some examples included large pockets of slush which made the ocean look like a thick soup as well as small patches of pancake ice which are circular pieces of ice just a few feet across. It was quite a profound moment to see the ice from the ship for the first time, but particularly so for some people in our group who had never seen sea ice in person before.

After picking up the seismic instruments we began our transit into the much more concentrated area of the pack ice in the central Arctic Ocean. Our target was an area around 85 degrees latitude and 135 degrees longitude, here the Transpolar Drift takes sea ice towards Greenland and the Fram Strait over the course of the year and an analysis of past sea ice drift trajectories showed this should be the optimal place to find a floe that meets our numerous scientific and logistical requirements. For me, the transit through the main pack ice on the ship was an extraordinary and unique experience compared to how I have seen and worked on the ice in the past. Much of my work uses satellite data (most recently from NASA’s ICESat-2 mission launched just last year) to determine sea ice thickness, and I have also flown many times over the Arctic ice as part of NASA’s Operation IceBridge mission. That work gives me a very high level view of the ice. For example, I can use satellite data to create a map of Arctic sea ice thickness to see large-scale properties such as where the ice is thick and thin, and see changes from year to year.

But viewing the ice from the ship is quite different, the intricate details and variability of the ice becoming the dominating factor as ice is viewed from just a few feet away, and the vastness of the area is brought into more human scales as we travel around at much slower speeds than a plane or satellite flies. This change in perspective allows me to again see the Arctic not as some small place on a map with the ice having a thickness which changes rather smoothly over large distance, but as a quite vast and remote area with enormous variability. It is this merging of perspectives and (soon) data, from the ground level up to the satellite level that I will use to add to our collective knowledge of the Arctic sea ice pack and contribute to the understanding of the large changes which are occurring to it. In trying to grasp the enormity of the changes which are occurring, a stark thought came to my mind while viewing the ice from off the side of the ship. The thought that when my children reach my age it is unlikely they will be able to witness what I am seeing right now, because it is likely by then that much of the Arctic Ocean will be free of sea ice at the end of the summer melt season.

Now we’ve come close to our target area and have embarked on a search for our “home” for the next year. That home is an ice floe which has just the right characteristics of size, thickness, and representativeness to support the huge suite of scientific instruments and projects that comprise MOSAiC. Several potential floes have been identified from satellite data, but until we deploy people on the ground to measure the thickness of the ice it is uncertain which one would we should choose. Today we investigated a candidate floe with a more extensive survey team. I got to join one of the teams setting out a navigation system for the floes. Since the ice is constantly drifting we don’t want to use just simple latitude/longitude coordinates from GPS, but rather to transform that data to a reference frame that moves along with the floe itself. My job on this particular excursion was not scientific, but serving as a polar bear guard. While I never imagined my career as a scientist would take me in this line of work, I’m thankful we were provided good training such that I could feel up to the task and contribute to the work on the ice today.

Being able to set foot on the ice floe and leaving the comfort of the ship was a humbling experience. This strange and dangerous place where no human had likely set foot before. An area seemingly frozen in time as the sun completes a dying circle around the horizon, setting ever sooner each day and giving way to the endless polar night over the course of the next week. But many changes are actually happening here in the Arctic and to the ice. They can be hard to see with human eyes at times, so we’ll continue searching for our new home until we find a place to set up our sensitive equipment to see better what is happening in the ocean, on the ice, and in the atmosphere.