The Lady Amber and R/V Revelle in Honolulu.

By Eric Lindstrom

Two ships in Honolulu were abuzz with action this last week preparing for SPURS-2, a detailed study of ocean salinity in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. The Roger Revelle, upon which all the scientific party sails, had to be loaded with many tons of scientific equipment and installations completed all over the ship. Lady Amber, the 20-meter (66-feet) schooner, was also readied for action with the installation of meteorological and oceanographic gear.

It was amazing to see what was completed in only a week under the supervision of chief scientist Andy Jessup (University of Washington). Containers from Seattle, Woods Hole, and San Diego were unloaded and equipment hauled to the ships. Many scientists and technicians dedicated the entire week prior to Revelle’s departure on August 13 for stowage, assembly, installation, testing, and securing of instruments and gear. It was a very quiet ship over the last 24 hours after we departed as everyone had a well-deserved rest and acquired their sea legs!

The Lady Amber crew successfully tested its new installation of scientific gear but suffered a schedule setback when the crew discovered that the ship required a new engine prior to departure from Honolulu. These arrangements are underway and we are appreciative of the support provided by the University of Hawaii as the Lady Amber work gets completed. Lady Amber is expected to leave Honolulu in about a week and catch up with Revelle at the SPURS central work site, eight days southwest of Hawaii.

Argo the cat, relaxing in the Lady Amber.

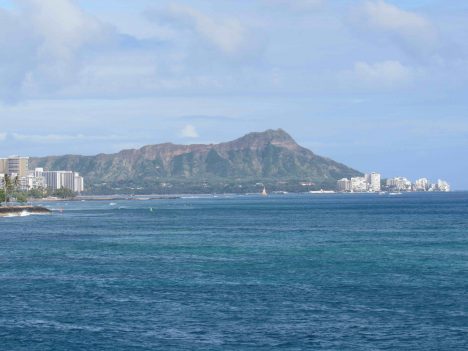

Weather was fine on Saturday afternoon for Revelle departure. It was a quick trip out of the harbor with a great view of Waikiki skyline and Diamond Head. We passed by the Big Island of Hawaii on Sunday morning, August 14, giving people one last chance at cell phone calls. The island, really the largest mountain on our planet (from ocean bottom to summit), is a phenomenal sight.

Goodbye to Honolulu!

On Sunday we had our first of weekly safety drills. Everyone got to learn how to decode the various horns that call for assembly, all clear, and abandon ship. We learned about survival suits and life raft deployment. Especially, we learned how to be safe on the Revelle and watch out for one another. We were encouraged to see the expert knowledge and conduct of the crew in their drills. It is over 2000 miles from Hawaii to the site where we begin work in earnest (deployment of moorings that pack the after deck). In the coming week, as we make the transit, the primary occupation will be testing and checking out various systems and training everyone for the complex operations to come. Once we are on site, we will quickly enter 24/7 scientific operations and we hopefully will have worked out all the glitches!

On a sad note, we had to leave our colleague Fred Bingham standing on the wharf in Honolulu, when we had expected him to sail with us. He was struck down with an illness that required he remain ashore and head home to Wilmington, North Carolina. His primary role in SPURS is as data manager. We are all assured that he will be on the mend very soon but we will miss his sunny manner and organizational skills.

The scientific party aboard Revelle is quite diverse – from first timers to old veterans. I’ll try to introduce you to the team in the weeks ahead. I am happy to report that I have seen no severe cases of seasickness during our initial day at sea. No doubt a few people are feeling a bit “green” but all are adapting well.

As always, I welcome your comments and suggestions for this blog. Send your messages to ejlindstrom@rv-revelle.ucsd.edu (case sensitive!). The expected frequency of the blog will be about one every two days.

The DC-8 departs Kona for American Samoa (credit: Dave Jordan)

The other day I had a unique and difficult experience. I was on the tarmac at Kona International Airport, Hawaii, and I watched the DC-8 take-off, with all my colleagues, our crew and my instruments on board. This wasn’t planned, and no, I hadn’t just missed my flight.

Somewhere between California and Alaska I caught a seemingly innocuous cold. Then somewhere between Alaska and Hawaii this cold stopped me from being able to equalize the pressure in my ears. On a normal flight this can be extremely painful and can risk lasting damage to the ear drum and hearing. On a flight where you simulate take-off and landing 8 times … well you can imagine.

We’d been told in our safety briefings to mention ear discomfort to the crew should it arise, so after waiting a little bit too long because I wanted to tough it out and not cause a fuss (very ill advised, don’t do that) I mentioned this to the crew. They immediately showered me with all kinds of medication to help and techniques to equalize pressure and reduce pain. This, and being able to ask the pilots to pause and level out for a bit when we were going down, got me through a few more descents, but the pain became really unbearable in the end.

The project principal investigator, Steve Wofsy, and crew came up with a plan to do our last descent in stages, leveling out every few hundred feet to make it less painful for me as well as being a new and excellent way for some of the instruments on board to sample the atmosphere. By leveling out for five or ten minutes at a time, they could collect samples at unique altitude levels for later comparison to see the vertical structure of the atmosphere here. I’m so glad it worked out that way.

Me having successfully landed in Hawaii with both eardrums intact (credit: Maximilian Dollner, University of Vienna).

We had two hard down days in Hawaii before flying to Samoa and I felt sure I’d recover in time. I thought things would clear up on landing, but they didn’t, and I spent the next morning in urgent care, getting prescriptions for antibiotics and steroids. I slept a lot and tried every trick in the book to clear my ears. However, nothing was improving.

Just in-case, I trained two of my colleague on running my instruments, and hatched a plan with my supervisor back in Colorado that if I couldn’t take the flight on Saturday, I’d fly commercial to New Zealand the next day and catch up there to do some maintenance and hand over properly to my colleague who’s scheduled to fly the second half.

I desperately wanted to be on that flight to Samoa. The last 14 months of work have been all preparing for this. I love the excitement of the flights and watching the data come in, the camaraderie among the team, seeing all these new and different places. I also hate the idea of not being strong enough for something, it’s a bug-bear of mine. Above all, this mission is too important to mess up.

And that’s when I realized, the mission really is too important to mess up. And that means, if its not sensible to fly, I do not fly. If I flew with bad ears and the pilots had to divert the course every instrument on that plane loses data. If I arrive in Samoa with a burst ear drum, not only is it much harder to deal with, but I’m a greater risk flying on subsequent missions because of the weak spot.

If I don’t fly, actually I’m proud to say, my instruments do pretty fine without me now. We did a lot of work to ensure they automatically cope with all the pressure changes and other challenges of the flights, and it has paid off. And the features I notice along the way, well I get so darn excited about them I tend to explain them to anyone who’ll listen, so my colleagues can spot a lot of them for me after five flights together now. We have a chat link set up with the DC-8 while it flies, so for each of the two flights I’ll miss I’ll be online on the ground diagnosing any issue that come up for the instruments and helping out my colleagues who are kindly running them for me.

I tried until the last minute, even during the pre-flight meeting to equalize my ears, although I’d told the science and mission directors the previous evening that if there wasn’t a dramatic improvement I would not be flying. They didn’t equalize. In fact they still haven’t. My team are in American Samoa, preparing to fly to New Zealand and I’m in Hawaii on strict medical advise not to fly for three more days. I won’t even catch up in New Zealand. Instead, I will fly back to Colorado as soon as my ears allow.

Plumeria flowers on Kona, Hawaii (credit: Christina Williamson)

As science gets to be more about successful collaborations, given the large scale and complex nature of the questions we’re now addressing, being a good scientist becomes more about good team work. This is no place for personal heroics or thinking you’re not expendable. Sometimes, a little humility and discretion can go a long way.

Sunset on Kona, Hawaii (credit: Christina Williamson)

Christina Williamson blogs regularly about the ATom Mission and other adventures in atmospheric science at christinajwilliamson.wordpress.com and tweets as @chasingcloudsCW.

Last Saturday, part of the team arrived safely in Kulusuk! Olivia, Clem and Stefan flew in two hours with Air Iceland from Reykjavik (Iceland) to Kulusuk (East Greenland). This is one of a few international airports on the east side of Greenland and also the home of our container full of camping and science equipment. For me, this is my first time in Greenland and I am glad I can share these first impressions with you.

Olivia and I about to board the plane to Kulusuk.

The current weather in Kulusuk is absolutely splendid: blue skies, light wind and around 5 C (about 40 F). This also provided us with very nice views from the plane. One hour into the flight, the dark mountains of the Greenlandic coast appeared, covered in snowy patches or more permanent glaciers. Behind them, in the distance, the vast white ice sheet was visible. As we flew closer, the icebergs drifting in the ocean also become more and more impressive. Glaciers that terminate in the ocean sometimes lose large portions of their floating part as icebergs, which can ‘survive’ for quite some time in the ocean. The white ice in contrast with the light blue water surrounding is really stunning. After 15 minutes of watching in awe and snapping photo after photo, we landed on the dirt runway of the Kulusuk airport.

First view of the coast of East Greenland. The ocean is filled with enormous icebergs.

Fantastic view of a huge iceberg; the walls are likely 10-20 meters high. Also note the nice crevasses (the diagonal lines) on the surface.

We brought our bags to Hotel Kulusuk, which is actually the only hotel in the village of Kulusuk, and decided to use the rest of the day to check on all our equipment. Most of the tents, sleeping bags, and science equipment is stored in a large container at the airport. We walked to the airport (about 20 min) and on our way there, we heard a loud noise and saw part of a gigantic iceberg collapse, very impressive.

At the airport, we luckily found all 33 boxes we shipped this spring nicely stacked in a corner of the building. With that, the big inventory could start! We unloaded the container and organized everything in different categories: camping, science, snow mobile, and not-needed-this-year. We made great progress, but need a couple more days to organize everything and put it in boxes (about 70 in total!). In the end the limiting factor is the weight that can be carried by the helicopter. The schedule for the coming days is that Rick and Kip arrive Sunday, Nick on Monday, and on Wednesday and Thursday we get transferred to the field site. At least, that’s the plan.

Clem and Olivia using airport baggage carts to move our boxes filled with equipment.

All our stuff in the container.

All our stuff out of the container.

Our dinners for the next three weeks.

Finally, a little bit about myself. I am Stefan Ligtenberg and a post-doc at Utrecht University in The Nethelands. During my current 3-year project, I aim to simulate 3D water flow in the firn aquifer using a computer model (vertical percolation of surface meltwater through the snow to recharge the aquifer and lateral flow downslope within the aquifer). To do so, I use a snow model in combination with an adapted groundwater flow model. One of the important constraints for these models is the so-called hydraulic conductivity; how fast can the water move through the porous snow. One of the main goals of this years field work is to better measure this conductivity.

Greetings from Greenland,

Olivia, Clem and Stefan.

The R/V Revelle.

By Eric Lindstrom

I am writing this while on a plane headed toward Honolulu to join the Research Vessel (R/V) Roger Revelle for six weeks at sea in the Pacific Ocean. It feels great to be heading to sea again. This NASA field campaign will last more than a year, with intense shipboard work near the beginning and end of the year. A web of sensors will be deployed to monitor one oceanic region over an entire year.

As Physical Oceanography Program Scientist at NASA Headquarters for nearly 20 years, my primary job is supporting our satellite missions related to measuring physical characteristics of the ocean (principally, temperature, salinity, sea level, and winds) and supporting the oceanographers that generate knowledge from such data. True understanding requires our fully appreciating the variations of the satellite data in the context of ocean physics. And that requires getting out there and getting wet from time to time!

Your blogger, Eric Lindstrom.

R/V Revelle (home port: Scripps Institution of Oceanography, San Diego, California) leaves Honolulu on 13 August 2016 and returns to Honolulu on 23 September. The central location of the field work is about 8 days voyage southwest of Hawaii at 10N, 125W. Details of the expedition plans are available here. I hope to bring you a steady stream of expedition blog posts between now and the end of September 2016, including why NASA is focusing attention on this particular spot in the open ocean.

Since NASA’s launch in June 2011 of the Aquarius instrument to measure ocean surface salinity from space, the agency has embarked on field campaigns to understand surface salinity in great detail. This work has illuminated new ways of thinking about the ocean’s role in the global water cycle. Our field campaign, dubbed Salinity Processes in the Upper Ocean Regional Study-2 or SPURS-2, is the latest work to link the remote sensing of salinity with all the oceanic and atmospheric processes that control its variation.

The ocean is the primary source of moisture for the atmosphere. Evaporation of water from the sea surface leaves the ocean saltier (more saline). Precipitation over the ocean leaves the ocean fresher (less saline). The global pattern of average salinity at the sea surface approximately represents the balance of evaporation and precipitation at any locale (other factors such as river runoff, ice melt, and ocean motion and mixing complicate the picture). Many details of the interaction between ocean and atmosphere that lead to moisture transfer and signatures in ocean salinity are poorly understood. SPURS-2 is particularly focused on how, in one of the rainiest places on Earth, rainwater enters and impacts the ocean. Through this blog during the coming month, you will hear more about how and why oceanographers focus on such a problem.

The first SPURS campaign, which took place in the North Atlantic Ocean in 2012-2013, focused on the study of ocean processes where evaporation dominates the salinity of the surface ocean. I blogged during the September 2012 work from R/V Knorr. Among other things, we learned that surface salinity variations in that part of the world can be directly connected with precipitation patterns over the nearby continents. I’ll discuss that scientific finding and others in this blog over the coming month.

At the opposite extreme from SPURS-1, SPURS-2 focuses on an oceanic regime where precipitation dominates the salinity characteristics of the surface ocean. The two extremes call for significantly different approaches to measuring and studying the upper ocean. We will uses many of the same tools from SPURS-1 (instrumented moorings, profiling floats, surface drifters, and gliders) but deployed in new and novel ways.

The crew and scientific party on R/V Revelle will be more than 50 in all. As you read future blog entries you will get some sense of what its like for such a group to work closely together for six weeks in the confined space of an oceanographic research vessel. Seasickness? Food? Watches? Sleep? Drama? Boredom? Sea life? You’ll find out soon and get a sense of how some oceanographers go about their work, what technologies are involved, what is discovered, and how all this impacts lives, including yours, and what you might experience if you were aboard.

The DC-8 preparing to leave Anchorage, Alaska (credit: Christina Williamson).

We had a gently warm morning for takeoff to Hawaii, with sun peaking through the clouds. Getting above the clouds we had spectacular views of snow capped peaks. We made a missed approach at Cold Point, population 109 at the last census. Low clouds prevented us from seeing too much there visually, but through the instruments we saw that many chemical species were very low, perhaps because the air had been recently cleared by rain.

Mountain views leaving Anchorage, Alaska (credit: Christina Williamson).

Missed approach at Cold Point (credit: Christina Williamson)

We then flew over the Kodiak Archipelago, which I was told back in Anchorage is the place people go when Alaska feels too crowded! It looked very remote and intriguing.

From there it was pretty much a straight shot down the pacific to Hawaii, where we landed on the largest island, Kona. We passed through a ship track at one point, where we can clearly see the plume in lots of instruments, including the number of aerosol particles that I’m measuring. Other than that it feels quite featureless. It’s funny to go out and purposefully measure “almost -nothing”. It’s not nothing, its the atmospheric background and there’s always stuff going on, but its the kind of stuff I’ll only be able to see once I look at a lot of data together, finding patterns over space or correlations with other measured values. It may not be the most exciting data to report here, but in terms of our long-term understanding of atmospheric processes and rigorous testing of global climate models, it’s absolutely key.

We keep the cabin cool while we fly as it’s good for the instruments (although less comfortable for the humans). We knew Kona would be very humid, and if we just landed and opened the doors to let humid air in to condense on cold instruments we’d be in trouble, so we added heat in the last descent to stop this from happening.

It was indeed hot and humid when we landed. The ocean was a beautiful bright turquoise as we flew over it and the volcano was shrouded in mist. Our logistics manager had arrived before us and came onto the plane greeting each of us with traditional leis to welcome us.

Leis handed out by Dave Jordan (NASA AIMES) as we land in Kona, Hawaii (credit: Karl Froyd)

Wandering along the shore that evening to have dinner watching the sunset over a palm fringed beach it felt surreal that we had breakfasted in Alaska and seen so much in-between.

Palm trees on the shore on Kona, Hawaii (credit: Christina Williamson)

Christina Williamson blogs regularly about the ATom Mission and other adventures in atmospheric science at christinajwilliamson.wordpress.com and tweets as @chasingcloudsCW.