The ATom mission is the first to traverse the whole lengths of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans while making atmospheric measurements from the ocean surface to high altitudes. When we planned ATom, one idea was to compare pollution impacts between the oceans. I expected that human activities would have much greater influence in the Atlantic, because it is smaller than the Pacific and it receives industrial emissions from both sides – the U.S. on the west and Europe to the east. The big emissions from Asia appear to go north to the Arctic, mostly bypassing the Pacific.

Already, our measurements have shown me that our notions did not always match reality. The North Pacific was full of pollutants from Asia, but not from industry as we might have expected—they came mostly from forest fires in the Arctic. Near the coast of California, we did see industrial pollution, but even there, the impact from the large forest and brush fires raging through the Western U.S. this summer was much greater.

So we departed New Zealand and flew to Punta Arenas, Chile, across the tempests of the Southern Ocean off of Antarctica. We found the cleanest air we encountered anywhere, although even there, we could detect very faint traces of soot and other combustion products. It was windy, snowy and cold in Punta Arenas.

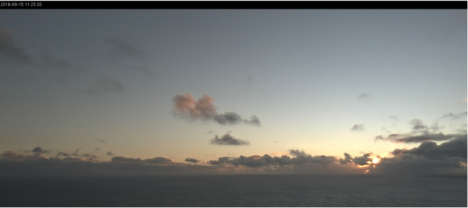

Crisp air had arrived from Antarctica, by the time we embarked two days later for the Atlantic. It was just as clean as it looked.

Crisp, clean sunrise seen from 500 ft over the South Atlantic east of Argentina. Photo: NASA DC-8 forward camera.

We headed from Punta Arenas to Ascension Island, a small, isolated, mostly barren volcanic protrusion emerging from the very center of the Atlantic at the Mid-Atlantic ridge, where the ocean basin is created, 12 degrees south of the Equator. It is extremely remote, more than 1000 miles from the nearest land.

Ascension Island, our destination in the middle of the tropical South Atlantic. Photo: Steven Wofsy

An hour or so after leaving Chile, we crossed the frontal region of stormy weather that separates the wintry middle latitudes from the subtropics and tropics in the south Atlantic—the southern polar jet stream. Air quality started to deteriorate immediately after we had crossed the jet stream, and pollution got stronger and stronger as we approached Ascension. By the time we arrived there, smoke and haze were so thick we could not see the surface of the ocean looking down from above. Here we were — actually dead center in the middle of the ocean — and pollutants from brush and forest fires in Africa were as heavy, or heavier, than the smoke and haze we encountered when we started out in Palmdale, California, where there was a large brush fire nearby and the City of Los Angeles just upwind!

Dense smoke and haze obscure the sunset as we approach Ascension Island, in the center of the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Compare this image with the sunrise that we observed on departing Chile! Photo: Steven Wofsy

I was not surprised to find pollution at Ascension, its presence had, once again, been forecast by our modelers, Junhua Liu and Sarah Strode from Goddard Space Flight Center. But I was stunned at how dense and extensive this pall of haze and noxious gas was. We found quite a bit more than what the models predicted. No wonder we had earlier seen African pollution way out in the Pacific, 3/4 of the world away from the source!

We had wonderful hospitality from the U.S. airbase on Ascension, but this part of the trip was really discouraging. The rocky little island was inhabited by all manner of invasive species—plants, rodents, feral livestock, etc. The accommodations were spartan, and we were mostly cut off from communications with the outside world. The air that we came to study was a mess. We had traversed 12 time zones in a few days, so our bodies wanted to sleep when we needed to be awake and vice versa.

We were thankful to our gracious hosts, but ready to move on to our next destination, Lajes Airfield on Ihla de Terceira in Portugal’s Açore Islands. On this leg of our trip, we crossed the Intertropical Convergence Zone once again. On the north side, there was still a lot of pollution from African biomass fires and a good dose of Saharan dust, too.

We arrived at Lajes just after a storm had passed through, putting us in air from middle latitudes. The air was much cleaner. We stayed at a quiet town, Praia da Vitoria-Santa Cruz, on Ihla Terceira, with comfortable lodgings and excellent restaurants that emphasized local seafood and produce. It reminded me of the fresh-as-ever cuisine of Provence, France. I slept a lot, and enjoyed the place thoroughly.

Praia da Vitoria-Santa Cruz, Ihla Terceira, Açores, Portugal, at sunrise. Photo: Steven Wofsy

But I admit to having had a feeling of unease. The atmosphere over the Atlantic was far more polluted than I had imagined, and a large fraction of the whole ocean was being affected.

Nevertheless, I came away refreshed and invigorated after two days in the Açores, and I think the whole crew felt renewed and eager for the final legs of our journey—on to Greenland, ground zero for climate change.

Always fascinating to read about your observations and findings.

Read a bit more about Ascension Island and the invasive species.