Charismatic megafauna

The oceanographers amongst us are often hard pressed to distinguish ourselves from marine biologists. Whilst many in the general public like to imagine our work surrounded by dolphins and resembling something out of a Caribbean vacation, the reality of tracing global biogeochemical cycles and deciphering complex bio-physical interactions in a dynamic and rapidly changing ocean for some reason is less inspiring – though of course much more important. Oceanographers study the ocean as a system and the ocean has critters in them, more numerous than the stars in the heavens, so yes, we also study critters. Rarely the charismatic megafauna though. While some oceanographers do study mammals, on this NASA NAAMES mission the largest animals under consideration are fish. Nonetheless, when the call goes out that dolphins are in sight – most frequently spotted by Luis Bolanos (OSU) – many briefly drop their important atmospheric or oceanographic research and run out to see the dolphins playing with the waves generated by the ship or riding seemingly effortlessly on the bow wave. The other day 2 sprinted by the side of the ship, as the R/V Atlantis made almost 14 knots (16 miles/hr; 26 km/hr). It was cool to hear them exhale, really seemed like they were doing a sprint. A sprint that lasted over 20 minutes and delighted those of us fortunate enough to see. So while most of the time aboard is focused on our research, sometimes we can’t escape the charisma of the megafauna to distract us from microscopic particles or plankton. It adds to the wonder of it all.

Atlantic common dolphins. Photo: Susanne Menden-Deuer

3 musketeer dolphins playing in front of the bow of the RV Atlantis. Photo: Susanne Menden-Deuer

Written by Susanne Menden-Deuer

One more day to go!!

NAAMES 2016 field campaign is almost reaching its end. We are going to reach WHOI on Sunday (Jun 5, 2016). A very relaxing summer atmosphere is prevalent on board R/V Atlantis. Having toiled day and night for nearly 3 weeks, scientists are enjoying their well-deserved break on our transit back. Galley transforms into a social club where most of the scientists hang out after dinner, while, few enjoy the evening with their guitars and well almost every one gather on deck to witness some of the beautiful sunsets. Unfortunately, due to heavy mist and fog like conditions we could not see the sun going down the horizon today.

Scientists relaxing on their way back to WHOI.

For me, this day began with photo shoot. All the scientists and crewmembers gathered on the bow to mark the ending of the field campaign with a group picture.

Group picture comprising of scientists and crew. Photo: Christian Laber

While most of the researchers are busy packing their instruments and wrapping up things, our instruments are still running and collecting data on marine aerosols. Marine aerosols affect the Earth’s radiation balance triggering a variety of global climate effects. Physicochemical properties of these aerosols is quintessential for the quantification of climate effects, solar radiation transfer and cloud processes. Changes in ecosystems due to warmer climates could alter the marine aerosol burden in the atmosphere, which in turn affects the global climate. The main focus of our group is to understand the impact of the biological cycles of phytoplankton on marine aerosol particle composition and in turn their impact on climate. The information from this study may be used to improve climate model predictions of current and future climate changes. To achieve this goal, we measure physicochemical properties of ambient marine aerosols in real-time throughout the cruise using a suite of real time instruments.

Our group consists of four researchers taking care of variety of instruments. Our daily routine includes loading filters to collect marine aerosol particles, changing desiccants, data acquisition, and data consolidation and processing. In addition, we take turns to monitor our instruments. Although, our routine is simple enough on a sunny day (when all our instruments behave properly), it gets quite exciting and stressful when the instruments misbehave (which is what we often encounter). Some of our instruments are highly sensitive and needs extreme special care and we had our own little adventures with these instruments. I can safely say that against all odds, our team (Derek Price, Chia-Li Chen, Maryam A. Lamjiri) managed to successfully complete the campaign and are looking forward to return and analyze the data in detail.

Written by Raghu Betha

The library is packed to capacity as the science team convenes for our daily meeting. We sit, some in comfy chairs, some two to a comfy chair, and some on the floor. We crane our necks towards a projector screen. For the first time in days nearly all of us are in the same room together at one time, and there is a sense of camaraderie.

As you may know, we are heading back to Woods Hole after days and nights of feverish sampling. You can usually find someone in the entertainment room watching a movie. Last night it was the classic The Princess Bride. Our job is not over. We are still running experiments, which will end just shortly before we reach shore. Oceanic and aerosol data is being processed, although some analysis will have to wait until we reach shore. At the same time, we are starting to dismantle and pack up any equipment we can. Once we reach shore, in a similar frenzy to how sampling first started, I imagine we will swiftly jump into action to get equipment loaded off the ship so that we may head home sooner.

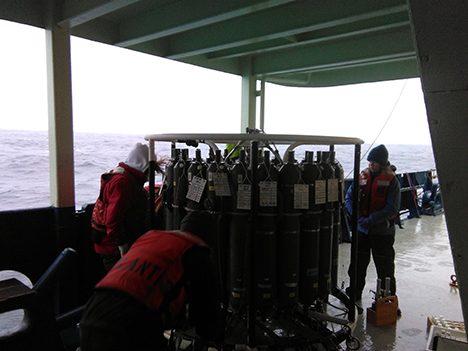

This is my first research cruise, and every day is a new experience. At each station, I measured dissolved oxygen from the Rosette using a titration system, aka Titration Station, provided by Woods Hole. A computer program controls the titration for the most part, instead of the traditional method of pipetting drop by drop until a color change occurs. It can still be a daunting task when the ship is pitching and rolling about.

Titration Station.

We push back the clocks one hour tonight, so that ship time will be the same as the East Coast. With each day bringing us a little closer to Woods Hole, we realize our time on the R/V Atlantis is nearly at an end.

Ocean view. Sadly, dolphin and whale free.

Written by Stephanie Ayres

By Walt Meier

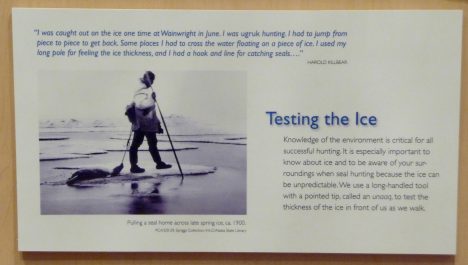

A sign at the the Inupiat Heritage Center in Barrow, AK.

Jun. 1, 2016 — We started our last day of the camp with a morning visit to the Inupiat Heritage Center to learn more about the indigenous local culture. Many of the Inupiat in Barrow still live their traditional subsistence lifestyle – hunting, trapping, and fishing for food. They do however take advantage of modern technology to make their way of life a bit easier and safer. For example, now machines have replaced dogsleds and rifles have replaced harpoons. But for some things, the old ways did not need to be modernized: the sealskin umiaq kayaks are lighter (easier to carry across the ice) and more navigable in the narrow leads of open water common to the area than anything manufactured today. And the fur-lined coats, pants, and boots are lighter, warmer, and repel moisture better than any modern outdoor gear.

A painting of whale hunting at the Inupiat Heritage Center.

The Inupiat way of life is governed by the seasons. There is a season for whale hunting, for seal hunting, for polar bear hunting. The dark, cold winter season is a time to stay indoors and sew new clothes or repair old clothes. Festivals mark the seasons where the community comes together to celebrate and reinforce the bonds between families.

After visiting the heritage center, we headed back to our base for a final meal. Several times during the week, our field leader, Don Perovich, said that the key for a successful field expedition is “to eat as much as you can as often as you can.” And we were certainly well fed throughout, with plentiful sandwiches, instant soups, chips and crackers, and all-important chocolate for our typical mid-day meals. But our final meal in Barrow was a step above, thanks to Elizabeth Hunke at Los Alamos National Laboratory. She proved herself not only a top-notch sea ice modeler but also a great chef, putting together a delicious meal of spaghetti, garlic bread, and salad.

Last meal in Barrow.

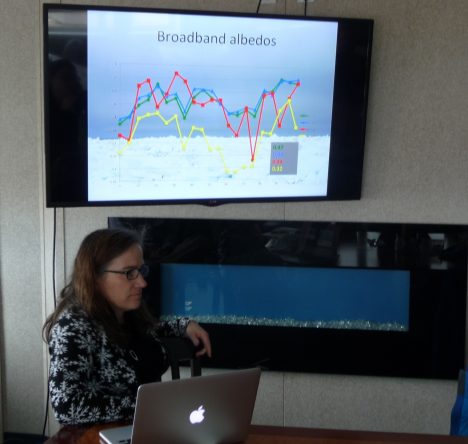

Then it was time for our final sessions, presenting the data we collected and discussing our Grand Challenge efforts. Unfortunately, the data collection the previous day did not go as smoothly as we had hoped. We couldn’t collect albedo measurements because the instrument didn’t work yesterday. But this type of things is not at all unusual in field work. As Don said: “In Arctic field research, it’s important to make a plan; it’s also important to not become too enamored of that plan” because something inevitably will go awry and you have be prepared to adapt.

So we couldn’t directly compare one of the key surface features between the two sites. However, we had other data we could look at. The new site to the north was 10-20 centimeters (4-8 inches) thicker than the original southern site. So there was less melt there and the ice was likely to last longer there. And while we lacked some data, we had models we could use. Many people think of modeling simply as predicting the future – and indeed models are used for that purpose (e.g., weather forecasts), but models, particularly climate ones, are also used to investigate processes and learn how climate responds to different parameters. Though we didn’t have albedo data, we could adjust albedo in the model and see how that affected how the modeled sea ice evolves in the future.

Grand Challenge results.

Several folks worked late into the previous night to process data and run the sea ice model. We obtained climatological weather data, input the data into the model and run it for the first two weeks in June. The results showed that the melt was strongly affected by the albedo of the surface and the amount of incoming sunlight, and that there will likely be substantial differences between the two sites. In a sense this isn’t terribly surprising, but to see such variation over such a small distance (the two sites were separated by only a couple miles) and within such short time periods (two weeks) is sobering. Large-scale complex models and satellite data cannot (yet) resolve such variability. There is still much research to do, and those of us at the camp have come away a greater appreciation for the challenge.

We finished up by discussing future plans. The goal of this camp wasn’t simply to get everyone together for one week, but to start new collaborations between modelers, satellite folks, and field researchers. We discussed several ideas to build upon the start we’ve made, keep momentum going, and convey what we learned to the broader sea ice research community. With that, it was time to head to the airport and begin our long journeys home.

Another tradition Don has is to bring a lollipop to each field expedition. When the expedition is done, he pulls it out as a reward for a job well done. At the beginning of our camp, he gave each of us a lollipop. It was up to us to decide when we were done. Some pulled theirs out after we wrapped up the meeting; some enjoyed theirs at the airport. I waited until the plane left the ground.

And so my adventure on the ice has come to an end. I can’t say I’m an expert in the field or ever will be. But it has been a rewarding week for me. I’ve gained a lot of knowledge about what it takes to do field work. I’ve gained an even greater appreciation of the value of field observations, as well as modeling studies. Hopefully I was able to give participants a greater understanding of satellite data. And finally, now when someone asks me if I’ve been on the sea ice, I can say “Indeed I have!” I still have the taste of the lollipop in my mouth to prove it.

Until the next time, Walt.

After escaping from heavy seas, we are heading back to port. This will be not a short travel, it will take about 5 days to arrive at Woods Hole. But all the time and effort of science team and crew members are worthy in order to explore one of the most amazing ecosystems: oceans.

One drop of seawater is a whole microbial universe. I like to imagine this micro universe as a jungle, full of organisms of different kinds and sizes, predators eating others for meals, bunches of little organisms working together to produce food or defeat a stronger one which eventually will be a meal, or even some guys eating the leftovers of a big feast. In these descriptions you can imagine jaguars, ants, piranhas, or vultures, but no, I am talking of tiny living beings such as bacteria, copepods and protists.

There are many ways to classify these microbes: by size, shape, or which functions they carry out in the community, just as we do with animals and plants. Sounds easy, but is not; these features are difficult to describe in microorganisms simply because, well, they are micro. Even with the best microscopes available, microbial characterization is not an easy task, and that is where our job starts. As all living beings, microbes contain a genome made of DNA inside their cells. The genome is a whole set of instructions which allow the correct development and functionality of the cells. We take advantage of a set of genes (pieces of the genome which codify for individual instructions) that are common for all organisms and can be considered a fingerprint. The more similar this print (sequences of DNA components) is, the more probable we are talking about the same kind of organisms. So, we use this genome segments to classify the community of the samples collected at different stations and depths across the North Atlantic Ocean.

The CTD rosette where sample water is collected from different depths within the ocean. Photo: Luis Avellaneda

Doing this classification we can calculate at each sampling point the relative abundances of the different species that comprise the community, our microbial jungle. Why is this important? Well, imagine some part of this magnificent micro-jungle where we cannot see any bananas left in the banana trees; that would be a very strange situation, but if we know that in that jungle area the abundance of monkeys is very high, we can figure it out what is happening there. The same thing occurs in the microbial universe, certain organisms prefer to consume or produce specific compounds.

Having a high-resolution characterization of microbial species composition and how this composition changes at different sites or times, help us to correlate them to the different data that my ship fellows are generating. In that way we can describe this invisible jungle, their dynamics, and the collective consequences that these lively drops of water are producing in our planet.

North Atlantic common dolphin. Photo: Luis Avellaneda

Written by Luis Avellaneda