I am a part of the Saltzman research group. Tom, our fearless yet cheery leader, and Jack, our resident optimist, night owl, and my lab mate, man the instruments day and night. They make sure that every piece, from the Mustang supercharger to the tiniest of valves, runs smoothly. None of this would be possible without the electrical genius of Cyril, our invaluable engineer. We should really make bets on the number of instruments he saves by the end of the cruise.

Part of our mobilization team. From left: Clayton Elder, Tom Bell, Cyril McCormick, Mackenzie Grieman, and Jack Porter

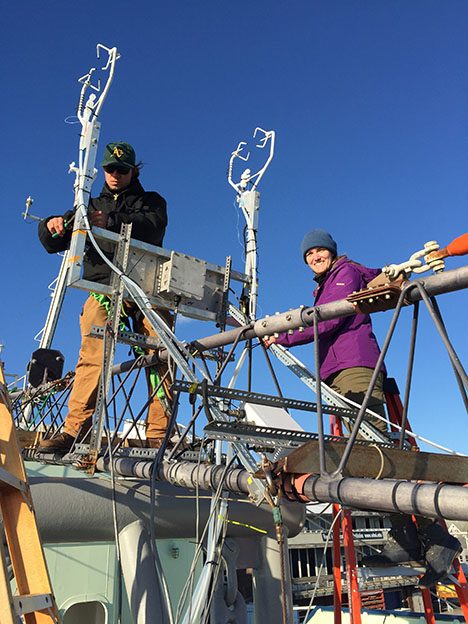

Our decorations on the mast are probably the most intricate and time-intensive parts of our set-up. They wouldn’t have been possible without our mast-builder, Clayton. In order to measure gases and aerosols, we need to bring them into the lab. We have a tube going from the top of the mast to an instrument in the trailer park that continuously measures dimethyl sulfide (DMS). DMS is a gas produced by plankton. DMS measurements will help to examine the relationship between plankton blooms and cloud formation. Tom, Jack, and Cyril (the guys) will talk about the intricacies of this in a later blog post.

Jack and me at the mast set-up

The mast set-up from the window of the van

I spend a lot of my time listening to the guys’ in-depth conservations about the functionality of their custom-built instruments between very short Jenga games and running sample vials to and from the trailer park. Running up to the vans at night is a bit of a surreal experience as you fight winds in the dark on your way to the red-lit bouncing trailer park. At least the van hasn’t sprung a leak like it did on the cruise in November (yet!)!! Fingers-crossed!

Written by Mackenzie Grieman

Creature comforts

What does it take to be comfortable on a ship? Good food? Check. A cozy cabin? Check. Diligent captain and crew? Check. We are very comfortable on our ride out to our first station, anticipated on Tuesday evening, May 17th. Before then, we have to cross a field of icebergs which excites the tourist in some of us but puts considerable uncertainty in our planning as we do not know how quickly we can progress through the iceberg area. Such uncertainty is completely standard on a research vessel, so we are indeed all in good spirits and very comfortable.

Creature comforts abound – Saturday is homemade donut day! Photo: Susanne Menden-Deuer

Image of a Ceratiun sp., a large dinoflagellate, sampled just south of Newfoundland as the RV Atlantis transits to the first station of the NAAMES-II mission. Photo: Françoise Morison

All set up – the incubators are wrapped and strapped down for transit (with Françoise Morison), Photo: Susanne Menden-Deuer

Making sure the light inside is right, Dr. Andreas Oikonomou and Françoise Morison installing a light sensor. Photo: Susanne Menden-Deuer

Drs. Craig Carlson (left) and Elizabeth Harvey (right) loading samples into the incubators. Photo: Susanne Menden-Deuer

Written by Susanne Menden-Deuer

Day three at sea!

The ocean has decided to get livelier as we get into day three at sea, although I’m told it’s still tame compared to November. Personally, I have become Dramamine dependent and almost always have a mint in my mouth (if you can’t tell, this is my first time on a research cruise). Despite my difficulty with the motion of the ocean, activity has been steadily increasing as we get closer to our first station.

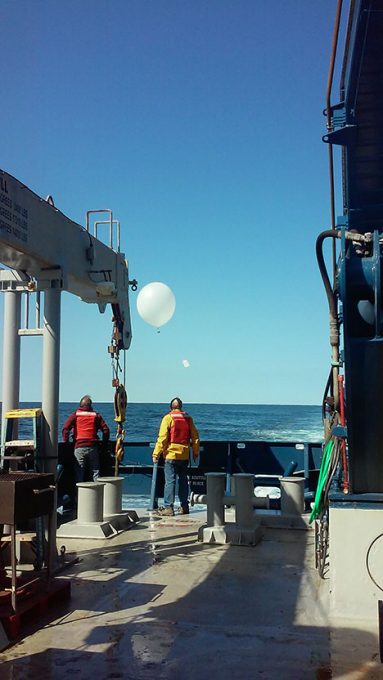

Cyril McCormick and Jim Johnson launching the first radiosonde from the aft deck of the RV Atlantis. Photo: Kelsey McBeain

Crew member Ronnie Whims laying out the mesopelagic fish net on the aft deck of the RV Atlantis. Photo: Kelsey McBeain

Cleo Davie-Martin measuring the amount of aerosols between the RV Atlantis and the sun, using Microtops. Photo: Kelsey McBeain

Living on a ship is a pretty surreal experience. I’m still half convinced that if I just walk around to the other side or go just a bit further, I’ll see land and something familiar. Watching the horizon does help with sea sickness, and it’s kind of fun to see the waves moving that far away. I’m also really confused about how tall people sleep on this boat. I fit in the bunks perfectly, but I am not a large person at all. I’m pretty sure they have to do some contorting, or just hang their legs off the edge to even fit, let alone sleep.

Doing these cruises, you are brought in to this odd little family where everyone wants to make sure you’re doing ok and talk to you and show you everything that’s going on. Everyone on board, science or crew has no problem plopping down next to you at meal times and starting some random conversation that has everyone at the table in stitches at some point. Even though I’m one of the newbies, I’ve been adopted in as though I’ve been here since the beginning, and that makes even the seasickness bearable (14 hours of sleep also helps greatly- at least for now).

Written by Kelsey McBeain

The R/V Atlantis doesn’t sail, as much as it moves the water out of its way. The waters so far have been calm, and progress is steady. We are still relatively close to land, as evident from a couple stowaways we picked up this morning, such as a summer tanager and 3 grey catbirds! Hopefully, these birds leave before we get too far out or they might be joining us the entire trip. I doubt Greenland is very hospitable this time of the year. Or any time of the year for these fellas and it would be a long trip home.

A stowaway summer tanager onboard the RV Atlantis. Photo: Susanne Mender

Calm seas and blue skies as we continue our transit to the NAAMES stations in the North Atlantic. Photo: Kristina Mojica

If you could ask only one question about the water drops in a cloud, you would ask “How many?” Solar absorption, chemical processing, and even a little precipitation can be gleaned from this question. If you could ask two questions about water droplets in clouds, you would next ask, “What size?” Knowing both number and size reveals significant information about cloud lifetimes, and dynamic processes like rain formation. This is information we can obtain from using radar and lidar technologies.

Our group focuses on the third question, “What are they made of?” The chemical composition of particles near the earth surface can provide information about how many particles will form into cloud droplets, and ultimately how many will be returned by rain. Our instrument exposes particles to water vapor concentrations typically found in clouds, and can count directly the number of aerosol that have cloud forming potential. Obviously, we cannot walk the instrument out to the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, hence the expedition.

Sea life is a lot like lab life, except now the lab moves a little, and there is potential for hurricanes and icebergs. I am consistently surprised by the lack of complaining from the group. Measurements at 04:00 don’t seem to bother anybody because these are THEIR projects. They specifically wanted to do this, and here we are. I still stumble into walls from time to time, but the food is good and so are the people. In life, what more can you ask for?

Written by Joseph Niehaus

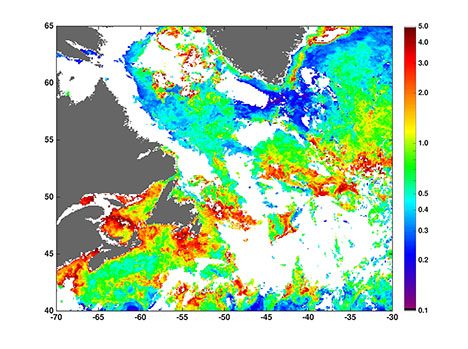

This morning started out full of excitement. The weather was beautiful, sunny and relatively warm. The first nice day many of us experienced since we began trickling into WHOI over the last week or more. The day had finally arrived, we were leaving to start our expedition. Everyone was on deck, many skipping breakfast to witness the lifting of the gangway and the slow departure from shore. Then, to our dismay, we noticed that the gangway was being detached from the crane while still on the dock. We were soon informed that a technical problem had arisen on the ship and could not be corrected in time for us to leave within the small window created by the slack (low) tide. Unfortunately, this meant that we would have to wait 7 hours for the next window. During the science meeting that followed, chief scientist Mike Behrenfeld informed us that we would set sail during the coming high tide which would occur around 1500, irrespective of whether the technical problem could be solved. We have a 7 day transit to our first station and we are anxious to get there while the phytoplankton are still blooming. Needless to say, we are closely monitoring the event using ocean color satellite imagery.

10 day satellite composite from May1-10th of MODIS aqua Chl in the North Atlantic (units are mg m-3). Land is depicted in grey, clouds or ice in white. Figure provided by Toby Westberry.

The aim of the NAAMES-II expedition is to capture the peak of the bloom in the northern region of the North Atlantic and its’ inevitable decline as we progress southward. The hope is that the data obtained during the cruise will demonstrate underlying regulatory factors responsible for both bloom formation and decline. The underlying hypothesis being that the acceleration of the bloom occurs due to the positive affect of increasing availability of light on phytoplankton growth rate occurring in nutrient replete (rich) waters, and the offset between these increases in growth rate and parallel increases in mortality processes (such as viral lysis and microzooplankton grazing). In contrast, the deceleration would be a consequence of either phytoplankton growth rate stabilization when they achieve their light saturated maximum growth rate or growth rate decrease due to nutrient limitation of surface waters. In either case, mortality rates can “catch up” to phytoplankton growth rates. Once this occurs, mortality rates exceed growth rates and the bloom declines.

The delay did little to dampen the work occurring on board. Aside from the general science meeting, there were small meetings within groups which covered how measurements would be taken, the person responsible and the timing of schedules to make sure all bases would be covered and everyone would still get adamant rest while at station. There was also a general ship safety meeting which covered different alarm signals and how scientists should react to them. This was then followed by a fire and abandon ship drill. During the fire drill, scientists don life vests and muster in the main lab equipped with hats and survival suits in the event that abandoning the ship was required. During the abandon ship drill, several scientists wiggled into their survival suits to make sure they are capable of dawning them were the need to arise. This is always a humorous situation as it makes everyone look like big red gumbies.

Kelsey McBeain, a master’s student from the lab of Kim Halsey, dons the survival suit during the safety drills. Photo: Kristina Mojica

After what seemed like an eternity, 1500 finally arrived. Once again, all scientists were on deck to watch the event. And there was nothing but smiles and high sprites as we moved away from the dock and waved our goodbyes to colloquies watching from shore. Finally, our expedition has begun. On our way out, we were blessed with calm seas and of course a beautiful sunset.

Sunset onboard the RV Atlantis after departure from WHOI, Photo:Kristina Mojica