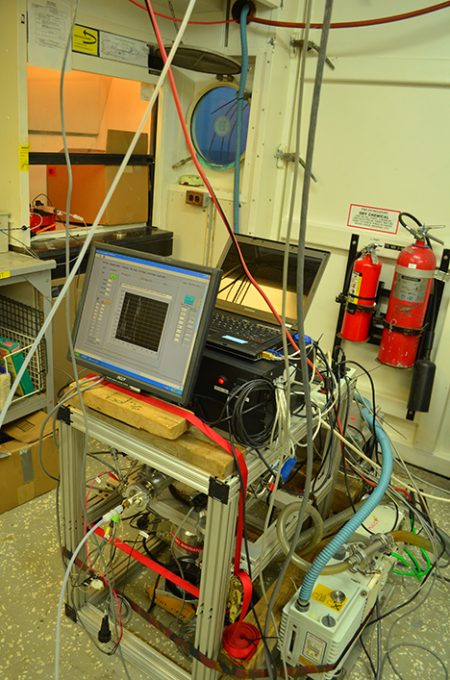

My eyes begrudgingly opened today around noon and the slow but steady accelerations of the rocking ship made their way into my consciousness. I hardly ever wake feeling thoroughly rested but the excitement of starting another day at sea always drags me out of bed. The start of a work day on-board is always preceded by a large cup of coffee and some time spent enjoying the view on the fantail. As I stepped outside the crisp North Atlantic breeze bit at my face and hands; a small price to pay for such an awesome start to the work day (I mean c’mon, there are people sitting in traffic right now). I observed the seabirds for a while, finished my coffee, and headed into the lab to check the instrument. Two of my co-workers, Tom and Mackenzie, were there hovering over our mass spectrometer (a mass spectrometer is a tool chemists use to detect certain molecules in air). These instruments can be bought off the shelf but in our lab we design and build them ourselves, which I think is totally friggin’ cool. However, that being the case, the thing is constantly broken. Mackenzie was shouting out numbers to Tom who was scribbling them down and I could tell from the tone of their voices that something had indeed gone wrong. After a while, I gathered that one of our pumps that delivers an isotopic standard to the instrument had broken. The inevitable constant barrage of broken instruments and faulty software must be matched by our ability to dream up solutions. Our secret weapon in this battle is our instrument tech and first class ideas man, Cyril McCormick. Cyril represents an infinite source of possible solutions to any issue that may arise. If you think your hot stuff, go ask Cyril how anything electronic works and you’re in for a humbling experience. The chief scientist, Mike Behrenfeld, once casually asked Cyril how an optical mouse worked and got a 4 page report back the next day complete with a schematic.

Mass spectrometer used to measure the chemical composition of aerosols. Photo: Jack Porter

NAAMES-II scientists enjoying the sunset on the aft deck of the RV Atlantis. Photo: Jack Porter

The nighttime view of the RV Atlantis aft deck. Photo: Jack Porter

Written by Jack Porter

I’m part of the Russell research group, along with my colleagues Raghu Betha, Chia-li (Candice) Chen, and Maryam Lamjiri, from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Our group focuses on aerosols, which are microscopic liquids and solids suspended in the air. Aerosols may be formed over the ocean when wave generated bubbles burst and eject particles into the atmosphere. Aerosols are important to climate as they act as seeds for cloud droplets. The ability of water to collect on aerosols is determined by their size and chemical composition. We have several instruments housed in our sampling van that we use to determine these properties. The aerosols are sampled through an inlet that reaches 50 ft above the ocean surface.

A view of the interior of the Russell group aerosol sampling van. Photo: Derek Price

The aerosol sampling vans (affectionately known as the “aerosol trailer park”). From left to right, the PMEL van, the Scripps van, The UCI van. The inlet reaches 50 ft above the ocean surface. Photo: Derek Price

As our instruments sample aerosols continuously, we are able to sample beyond the designated stations of the project. We began measuring aerosols while at the Woods Hole dock, we have been measuring aerosols since we left port, and we will continue to measure aerosols until we return to port. To make sure everything is running smoothly, our group members take shifts to monitor the instruments.

An exciting aspect of this project is the collaboration with the NASA Langley Aerosol Research Group (LARGE) which provides the C-130 Hercules aircraft. The C-130 contains some of the same aerosol instruments that are in our sampling van. This allows us to compare our ship-based aerosol measurements with the C-130 aircraft measurements. We can also compare our aerosol measurements with the other aerosol groups onboard from PMEL, UC-Irvine, and Texas A&M.

The NASA LARGE C-130H Hercules aircraft as it flew by the R/V Atlantis on 5/19/16. Photo: Derek Price

Today there was a flyby of the NASA C-130 aircraft, which is always an exciting moment for us on the ship. Over a dozen scientists and crew gathered on the O3 deck to capture footage of the Hercules. The conditions were foggy this afternoon when the aircraft was scheduled to arrive. The C-130 was already upon us by the time we saw it. They circled the ship twice before disappearing into the mist.

We are now en route to station 2. Hopefully tonight the fog will clear and we can catch a glimpse of the Aurora Borealis!

Written by Derek Price

With day one of Station One complete, an opportunity is provided to reflect on the stations events so far. I woke up at to start the day at 11 o’clock, quickly helping myself to a cup of the ships endless pot of coffee and a hefty bowl of cereal. If this sounds like a very lazy Saturday morning to you, I’ll add that this is in fact 11pm, with the sun not due to rise for another five hours at our northern latitude. After deploying a series of drifters and vertical profiling floats to autonomously observe the water long after we have left the station, we started our first sampling of the day promptly at half past midnight. But we don’t start our work so early simply because we are excited about collecting our samples. It turns out that light can be the enemy of scientists wanting to study the world’s tiniest photosynthetic organisms. When the sun pops over the horizon, the light used in photosynthesis alters properties of the phytoplankton that we want to measure in a dark-adapted state. As a result, when the late spring offers abundant light and long days, we have to take advantage of every hour of darkness provided.

While the ship is busy with scientists running around in the wee hours of the morning, the ocean can still feel like a lonely place. Step out onto the deck to sample from the rosette, manage incubations, or run up to the aerosol vans to check an instrument, and the fog that lightly grips the darkness provides a sense of immense solitude. However, the light of the morning brings contrast to this feeling, as life abounds all around us, only camouflaged by the stillness if the night. Stowaway songbirds start singing in a small portside hangar. Local fulmars begin to gather near the A-frame at the rear of the ship, hoping for an easy meal to be dumped overboard. Even a pod of pilot whales is spotted in the distance, with rumor that this may be the same pod we observed here last November. Suddenly, the seas do not seem so lonely after all. And to top it off, today was the first fly-by from the C-130 airplane, which collected data on atmospheric gasses, aerosols, and ocean color to complement our shipboard sampling for the NAAMES study objectives. To see another ship on the horizon or planes traveling at 30,000 ft is generally the closest we come to others not on the Atlantis, so to receive a low altitude fly-by from our fellow scientists elevates the spirit, knowing we are important to them and they are important to us.

Local fulmars floating nearby of the ship. Photo: Christian Laber

Though most science stopped momentarily for the fly-by, as our colleagues flew back into the cloud line, we once again entered the labs to continue our first full station. And as of now, the day has been a great success. Many are still busy deploying and operating instruments, however those of us who started our day before the day actually started are winding down for an evenings rest. We expect to have a schedule like this for the next two weeks, so the early mornings have only just begun. I think there’s an old saying: Early to bed, early to rise, makes a person healthy, wealthy, and able to collect good data on phytoplankton.

The C-130 on its first fly by of the NAAMES-II expedition. Photo: Christian Laber

Written by Christian Laber

Greetings from Station Zero.

It sounds like something from a bad sci-fi movie, but we are indeed at Station Zero. On most oceanographic cruises there is what is called a “shake down day” or an opportunity to test all your equipment and methods with a test station before the actual ‘real’ sampling begins. Thus, we have conducted a modified version of our sampling scheme, and have dubbed where we stopped Station Zero. We were pretty excited to finally get to a point where we could drop our instruments over the side and collect water. Our excitement came with a midnight start time, but even the early morning hours could not dampen our spirit. Most science groups have worked for months to get prepared enough to take the first sample, so to actually stop and finally sample was exciting!

The first CTD cast of NAAMES-II being guided into the water by our fearless leader Mike Behrenfeld

We are anticipating starting all over again tomorrow morning with our first station. We have some indications from an Argo float that is nearby, that the spring bloom of phytoplankton we are hoping to capture is still increasing in abundance. This is exciting as we were hoping to catch the bloom in just this stage.

Picture of an Argo float being deployed during NAAMES-I

I wish I could say our occupation of Station Zero ended with an alien invasion, but I think that would just be my sleep deprivation talking. However, it did end with a great level of excitement about what tomorrow, and the first station, will bring.

Written by Elizabeth Harvey

As we progress on our journey north, it is as if we are travelling back in time through winter and on towards the Arctic. When we left Woods Hole, we were treated with blue skies, calm (occasionally glassy) seas, and reasonably warm air temperatures; a complete contrast to the November cruise! We have been extremely fortunate with the seas thus far and many of us have weaned ourselves off our seasickness medications. With it being late spring, the daylight hours are long and we have been treated to some spectacular sunsets (and if you’re keen for a 3:30 am start, the sunrises aren’t too shabby either)! The sea life has been more abundant than on the previous cruise with a number of whale and dolphin sightings.

Another beautiful sunset from the aft deck of the RV Atlantis. Photo: Cleo Davie-Martin

Watching the sunrise at 5 am from the O2 deck of the RV Atlantis. Photo: Cleo Davie-Martin

But that was all about to change as we entered the ‘ice field’ off the coast of Newfoundland early yesterday morning. Some of us were up at dawn (3 am!) to catch our first glimpse of ice, but alas, we were shrouded in a thick blanket of fog and could barely see 50 m from the boat. It was absolutely freezing and there was certainly an eerie feel; it seemed like we could have been surrounded by icebergs and have no idea about it. But by that point I wasn’t quite sure I even wanted to see an iceberg because if we did, we’d almost certainly be on top of it the fog was that thick (the ship’s foghorn was put to good use)… As the sun rose above the horizon, the fog began to disperse and the sky burned orange. It was pretty special, despite the lack of icebergs. Regardless, excitement bounced around the ship all morning; even some of the crew had donned their cameras in anticipation of the ‘ice’ we were about to see. The fog came and went again and the seas started gathering a bit more momentum. Both the air temperature and the seawater temperature plummeted below 0 °C and the waves began dancing in every direction. But alas, luck was not on our side and the icebergs remained elusive. The crew decided on the ‘path of least resistance’ approach (realistically, the safest option) and managed to clear the ice field by late afternoon. So, no icebergs, but we did get a taste of the Arctic temperatures and colder, rougher weather that is likely to stick with us for a few more days.

Foggy sunrise as we enter the ice field taken from the main deck of the RV Atlantis. Photo: Cleo Davie-Martin

This evening, we will arrive at Station 0; our first practice station! We will be getting up at midnight to begin overboard sampling and have a ‘wet’ run-through of most of the deployments we will be making at the real stations. I will be collecting water samples from the CTD rosette casts to look at the cycling of small volatile organic compounds by the plankton in the surface ocean (such as the dimethyl sulfide you’ve heard about in previous posts, which can be released into the atmosphere and lead to the formation of aerosols). We think that in surface ocean, the phytoplankton (the tiny ‘plants’ of the ocean) are producing these volatile carbon compounds, just like trees do on land. Have you ever noticed the smell of a pine tree? That comes from volatile compounds released by the pine tree! The phytoplankton do the same, especially when they get stressed out or die and begin to sink down through the water column. That leaves room for the bacteria to come along and feed on all the carbon compounds left by the phytoplankton (just the same as you eat all your vegetables, just like your mother told you…). Any volatile compounds that are not consumed by the bacteria can then get released into the atmosphere, where they have a number of important roles controlling our climate.

The water samples I collect are incubated in polycarbonate chambers that are bubbled with synthetic air; we use synthetic air because it is cleaner than the regular air we breathe in and so we can be sure that anything we measure comes from the seawater (and not the air). Our chambers are kept at seawater temperature and we have blue and white LED lights that we use to simulate the light conditions the plankton might experience in the surface ocean. Compounds that are produced by the plankton will be stripped from the seawater by the bubbling air and we can then measure them with our specialized mass spectrometer, the aptly named ‘James’ – because he is #007 of his kind! James has been kept very busy on the cruise so far, running almost 24/7, because we have been able to collect seawater from the clean flow-through line running through the ship (which pumps surface seawater through from the front of the ship). So we are excited to see what we find! Wish us luck for Station 0 tonight!

James Bond (aka 007) and his incubators. Photo: Cleo Davie-Martin