The NASA FSG folks and the rest of the science crew on the US Repeat Hydrography P16S field campaign have experienced some weather delays, which can be expected when working the Southern Ocean close in time to the Southern Hemisphere winter. They encountered 45-knot winds (~51 miles per hour) sitting on top of their planned sampling area at around 60 degrees South latitude. For the safety of all they could not conduct science under those conditions. So they traveled ~200 miles north to escape the weather and then returned southward once the weather had settled. Below you will see some freeze frame clips from the movie Joaquin Chaves captured showing the large swells and the dramatic gray skies of the Southern Ocean. The movie was recorded through the porthole, safe inside the ship.

In spite of the rough weather, the FSG fellows have taken advantage of some calmer days to deploy a radiometer. A radiometer measures apparent optical properties or AOPs. You might recall from Blog #2 that we discussed Inherent Optical Properties or IOPS that characterize the absorption and scattering (reflecting) of light by dissolved and particulate materials in the water. The measurement of IOPs can be done at any time day or night. AOPs on the other hand must be measured during the daytime, preferable when there are clear skies and the sun is directly overhead. AOPs describe how the light is entering and exiting the water column. Remember that sunlight contains a whole spectrum of colors that are determined by their wavelength. We see what is called the “visible spectrum” like what is in the image below.

As the sunlight penetrates the water column, some of the light is absorbed, some is scattered (reflected) backward toward the sky and the rest is scattered forward into the depths of the ocean. Water itself absorbs most of the red light, so we never really see a red ocean (unless there is something unusual in the water).

The character of the light that is reflected back out of the water can be different than what went in. More specifically, the wavelengths or colors that are reflected back out are the colors that were not absorbed or scattered forward. Think about when you are at the beach, say Ocean City, MD or Rehoboth Beach, Delaware. The water typically looks brown or green, right? This is because particles, including both algae and sediment (and water), are absorbing all of the blue and red light, and the leftover colors of brown and green are reflected back out. Conversely, for those of you who have seen blue water in places like the Caribbean or around Bermuda, the circumstances are different. There are very few particles or phytoplankton in the water to absorb the blue light like in the coastal water. Therefore, that blue color is reflected back out , which is why the water looks so blue and pretty. A radiometer that the FSG is deploying on this field campaign measures the colors and amount of the light entering and exiting the water column. The radiometer is hand deployed and, I can tell you, it’s a lot of work!

Satellite instruments, such as SeaWiFS (no longer operational) and MODIS-Aqua (operational) measures this light just like the radiometer so that we can get beautiful images that you can see below.

Our FSG fellas are working very hard during this field campaign. But every now and then you need to have a little fun. Mike Novak sent this picture of a snowman that was built on the bow of the ship. I think the eyes, nose, and buttons are raisins.

References:

http://ushydro.ucsd.edu/p16s-weekly-reports/

http://www.oceanopticsbook.info/

http://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: NASA’s Ocean Ecology Laboratory Field Support Group is participating in the US Repeat Hydrography, P16S field campaign under the auspices of the International Global Ocean Ship-Based Hydrographic Investigations Program (GO-SHIP). The US Climate Variability and Predictability Program (CLIVAR), NOAA and the NSF sponsor this campaign.

By Clément Miège

It might be hard to believe but yes, we are still in town! We have been delayed for a full week now, every day getting ready for a possible flight the next day, and every morning, we get the same message: “Unfortunately, there will be no flight to the ice cap today due to weather and bad visibility with low clouds, but tomorrow looks more promising.” Oh, no! Even if it is fully justified, it is always a bit disappointing the moment you hear that, but I think our team has a good experience already with this kind of delay and we are able to switch quite easily and still be happy and optimistic for a flight the next day.

The main helping factor that puts us back in a good mood comes from the weather forecast. Indeed, every day we are able to see a clear-sky window that makes us think that we will be able to fly the next day. Sometimes, this weather window can be very tiny, but it is always there! Good spirits!

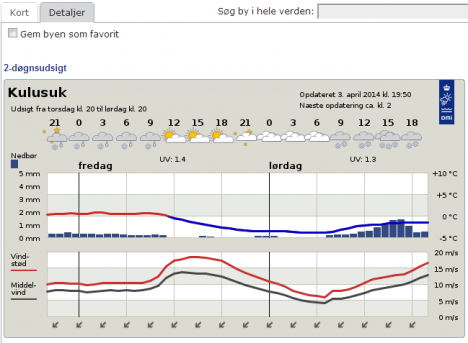

Tomorrow, again, it looks great, with a weather window in the afternoon (Forecast provided by the Danish Meteorological Institute .)

When you look at long-trend forecasts (beyond the following 48 hours), the weather is changing a lot in short spans of time. Often, there are significant changes from one forecast to its updated version a couple of hours later. For example, a 5-day storm, with heavy precipitation, appears in the forecast, but then it it is removed from the next update. So our moods shift quite a bit. For even longer trends, it becomes a different story. Rick shared with Ludo and me his experience with the so-called “Canadian Forecast”. It consists of making the last 5-6 days of a 14-day weather forecast always be nice and sunny, to keep people happy through the winter so they can anticipate the end of it. We can verify this “happy weather trend” in Greenland with our own Danish Forecast — the five last days of this forecast are always sunny. We are keeping a record of the forecast since we arrived two weeks ago, and we can say this is a regular pattern.

After checking weather forecast here, our daily duties are not done yet! Next, we take a look at the data from a weather station that is currently in the field, in our future camp site. We dropped the weather station as part of our cargo last week, but we did not have time to set it up. It is however transmitting data and our IMAU colleagues gave us access to the transmitted data. Unfortunately, the signal for diurnal temperature is getting weak, it’s almost nonexistent anymore, which means that the weather station is getting buried. More and more snow will need to be removed to access our equipment when we will get to camp (maybe tomorrow?) Next, we take a look at the Kulusuk airport’s flight schedule for the day. We can see for example that the Tiniteqilaaq flight is canceled (“aflyst”, in Danish) and that the Isortoq flight is delayed. Then, we do the same thing for the Tasiilaq heliport schedule and then we speculate (while drinking our coffee) where our flight fits in this schedule. We are getting quite good at this exercise! Our flight never fits and we are always rescheduled. But there are some events that are still out of our control. Three days ago, a domestic conflict in Kuummiut required the police Marshall to solve it. Since the Marshall is based in Tasiilaq, the helicopter had to fly him there. That day we had woken up at 5:30 am for a flight scheduled to leave at 7:05, which got rescheduled to 11 am, and after three additional hours waiting at the airport, it eventually became a cancelled flight. Needless to say, the helicopter never made it to the Kulusuk airport. We simply went back to the hotel in the pouring rain. As Ludo likes to say: “This is again craptastic; good times!”

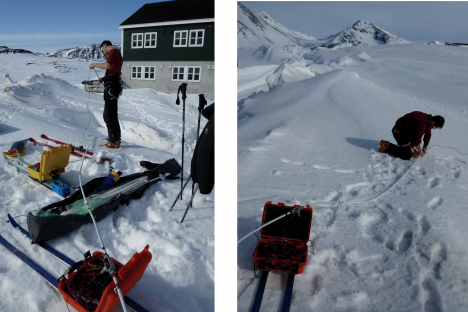

Sunday (March 30) was a beautiful day though, but we were not on the flight schedule — the pilots had to catch up with the Saturday flights had been cancelled. We took advantage of the nice weather to further test our field equipment. As I mentioned in an earlier post we will be testing a low-frequency radar system in the aquifer region on the ice sheet. Laurent Mingo at Blue System, who develops the IceRadar is letting us test a beta version of one of his radar systems. The IceRadar is currently used by many research groups on alpine glaciers, ice caps and ice islands. As such, it has been deployed in many regions of the world (Yukon, Rocky Mountains, Himalaya, Bhutan, Iceland, the Andes, the European Alps…) to perform ice thickness measurements and bed mapping, but also to look at the glacier englacial properties. I believe this is the first trip for the IceRadar to the Greenland ice sheet. So we are quite honored to have this system with us to try it over the aquifer.

Setting up the IceRadar for the first time in Greenland, with the 5 MHz antennas. The lower the frequency used for the radar, the longer the antenna has to be. For a 5MHz system, the antenna length is 20 meters (about 70 feet), and there are two of them (receiving and transmitting). (Credit: Rick Foster)

After the setup, we try our radar going from the seasonal snowpack to the relatively thin sea ice – that gives us important changes in terms of dielectric constant, which look quite obvious in the radar profile. The system total length is about 50 meters (164 feet), so no sharp turns are allowed! (Photo credit: Rick Foster.)

Getting the 40MHz IceRadar ready, you can see the difference of the antenna size — this is definitely easier to turn. (Photo credit: Rick Foster)

Rick watches Ludo and me maneuvering the IceRadar from the hotel. A new (feline) friend is also observing us, probably wondering what we are doing here! (Credit: Rick Foster.)

At the end of the day we have great news: the IceRadar is working well at the two frequencies tested, which is really promising toward our ice sheet measurements. YAY!

Finally, the hotel still does not have running water. As Ludo mentioned in an earlier blog post, the heating element in the water pipe supply line that prevents the water from freezing broke. And the road to get to the lake with fresh water is still being plowed, but the bad weather and drifting snow prevent the plow truck from making much progress. We are getting used to showering with a water bucket and becoming more and more efficient at conserving water.

Without water at the hotel, we are even more motivated for going to the ice sheet since we know we will not be missing a good hot shower anyway.

Our team has a really good feeling for tomorrow, so let’s hope for a “go” and keep our fingers crossed!

Cheers, Clément on the behalf of the aquifer team.

By Ludovic Brucker

Kulusuk, 31 March 2014 — When I started writing this post, my opening was: Greetings from (still) white-out and windy Kulusuk 🙁

Updated opening sentence: Greetings from now rainy Kulusuk 🙁 🙁

The nice thing about weather forecasts is that they change all the time, so you never get bored watching them. The bad thing about weather forecasts is that they change all the time. What we have been experiencing over the past days was bizarre. We had a storm with sustained high winds and some gusts. We then had temperatures high enough to work outside without a jacket. We also had calm periods alternating every half hour or so with sustained gusting events, so intense that it wasn’t advisable to get near the windows. Now, it is raining.

We spent the last couple of days patiently waiting a phone call or an email. During these days, we made sure to be able to arrive at the airport ready for a put-in flight within an hour notice, if necessary. So far, a good weather window coinciding with availability of the B-212 helicopter and its crew has not happened. We like to think that we will have a flight tomorrow morning. This might happen. As Daniel L. Reardon said: “In the long run the pessimist may be proven right, but the optimist has a better time on the trip.” We are optimists, despite the weather teaching us to be realists.

In the mean time, at the hotel… there is no (liquid) water available anymore since Friday. The pipes bringing the water from a nearby lake are frozen, due to an issue with the pipes’ insulation. This sounds typical here, but usually the hotel’s water tank can get refilled with a winter water truck (please, don’t ask for details, I tried to understand but couldn’t figure this story out completely). But now the road (the only one road) is buried under more than 2 meters of drifted snow. Hence, the winter water truck cannot resupply the hotel’s water tank. We were preparing to melt snow. As Rick thoughtfully mentioned it at breakfast this morning: “if you can’t get to the field, the field will come to you” © Rick Forster. However, the hotel employees went to pick up some big jugs of water for drinking, cooking and even showering at the village! Our record is less than 2 liters used per shower. The colder the water, the less you use of it.

Today, we moved the rest of our cargo up at the airport, including our personal bags. We are really hoping to go to the field soon (that is tomorrow early morning). Keep your fingers crossed for us! Signed: Ludo, one of the three optimists.

As many of you probably heard, there was an 8.2-magnitude earthquake off the coast of Northern Chile on Tuesday night. As with any earthquake around a coastal region or on the ocean floor, there is great concern about the formation of a tsunami. A Tsunami is series of waves with a very large wavelength. Think of a series of waves hitting a beach. The distance between each wave hitting the shore is the wavelength. Now picture a wavelength that is 100s of miles long! Because the wavelengths are so long, the waves travel at very high speeds, around 600 miles per hour, in the deep ocean. This is the speed at which a commercial jet plane travels! However, the wave height (the height from the base of the wave at the water line to the top of the wave) is very small, maybe a few feet tall. As you can imagine, a boat or ship in the open ocean wouldn’t even notice such a tiny wave.

Below is a screen shot from a CNN video report about the earthquake. In this video you can see how the waves propagate out from the source of the earthquake out into the ocean (red arrow).

The story changes, however, when the depth of the ocean decreases, such as when approaching land. All of that energy in that fast wave gets slowed down and subsequently the height of the wave gets bigger, and sea level near shore can rise at least 50 feet! Thankfully, our colleagues are out of harms way from tsunamis because they are in the middle of the deep, open ocean.

The ship and its inhabitants ARE, however, subject to waves that are created by storms and strong winds. Joaquin made a video of the wave action that you can see below. Here are some freeze frame ‘action shots’ from the video.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cBTORY0aalE&feature=youtu.be

And, lastly, I thought it would be good to show some pictures of how cold it is that far south and how challenging it can be to work outside on deck in the cold. In this picture you can see icicles hanging off the ship during recovery of an IOP package deployment.

Mike and Scott are having a conversation as they wait for the IOP package to return to the surface of the ocean. I wonder what they are talking about???

You can watch an entire IOP deployment below.

Lastly, when working so close to the continent of Antarctica, there must be a sighting of an iceberg.

Sources:

http://www.nws.noaa.gov/om/brochures/tsunami.htm

http://www.cnn.com/2014/04/01/world/americas/chile-earthquake/

By Ludovic Brucker

Kulusuk, 29 March 2014 — For our deployment to the field, we need two flights to bring our scientific equipment and camping gear. As mentioned in our previous post, we decided to avoid being on the ice sheet while the third storm system of the week affects the area. However, thanks to Air Greenland and its helicopter B-212’s crew, we were able to have a first cargo flight to the ice sheet on Thursday afternoon. This will allow us to be fully operational as soon the second flight brings our tents, food, more science gear, and us to the ice sheet!

Thursday morning, we went to the airport to meet with the pilot and hear his point of view about a possible cargo flight that same day. While snow-removing activities of the runway were underway, he shared with us his concern that our cargo (if left on the ice sheet with the current weather system developing offshore) may be blown away or heavily buried in snow. Since we did not have a single item fly away in Antarctica during our SEAT 2011-2012 traverse and its Christmas storm, we will make sure this does not happen in Greenland! Regarding buried items; it’s fine as long as the shovels aren’t buried themselves.

A snow plow removes snow from the second storm of the week at the Kulusuk airport . (credit: Clément Miège.)

In the afternoon, Clem and I took off with the cargo flight to unload it from the helo, and to build the cargo line. The sky was scattered with clouds, sometimes low, but it cleared up as we were approaching the ice sheet.

Transit from Kulusuk to our ice sheet location, near the settlement of Tinitequilâq. (Credit: Ludovic Brucker.)

We landed in the vicinity of our temperature probe system and its Argos antenna, which has been sending temperature measurements every day for almost a year now. With the help of the helicopter’s crew, it did not take long to organize a cargo line along the dominant wind direction to minimize snow drift.

Our cargo line on the ice sheet, near the temperature probe and Argos antenna we left behind in 2013. I’m finishing up by deploying a second cargo strap across the line and through the boxes handles. (Credit: Clément Miège)

Our objective was accomplished, the cargo was on the ice sheet. Step 1: Done! Done? Well, of course not. We still had to fly back… But in spite of everyone’s effort, we were not able to fly back to Kulusuk that day. The night was coming quickly and the pilot is not allowed to fly after twilight. Thus, we landed in Tasiilaq 3 minutes after twilight on Thursday. Tasiilaq is on the other side of the bay from Kulusuk, a 15-minute helicopter ride away. Tasiilaq is the largest city on the East coast of Greenland, with about 3,000 inhabitants, and it’s home for the B-212. We landed accurately on the B-212’s kart in front of its hangar so that it could be moved inside quickly. Suddenly, Clem and I were facing a situation for which we were not prepared.

For a less-than-2-hour round trip to the ice sheet, Clem and I were dressed in our warmest layers, and to face a variety of eventualities (including spending an unexpected night on the ice sheet) we had packed a tent, sleeping bags, food, water, extra jackets, gloves, goggles and hats, a satellite phone, two GPS, and a beacon locator. We knew that in our cargo there was more food, a cook stove, propane and white gas; these were in case for the inbound flight. For the outbound flight, we knew that the B-212 has some safety equipment too. That was all we had. But we were facing a different situation now: we were in the largest town of East Greenland, with the perspective of a storm arriving overnight, and forecasted to last several days.

Air Greenland found us a hotel and a warm dinner. Sweet, we wouldn’t be camping on the helipad. Past the first night, we woke up with the exact same landscape as in Kulusuk. I’m serious! Through the windows we could see the same white sky, land, and horizontal snowfall. Visibility? We still don’t know for sure; neither Clem nor I could tell because we had left Kulusuk with our contact lenses on and did not carry our glasses.

Past this first reality check, we headed to breakfast (dressed in our long underwear). We had a specific topic to discuss: what were we going to do during the next hours, days, week? The ideas ranged from finding a book, a toothbrush, an Internet connection, an alternative to water for our contact lenses, learning Greenlandic, finding a boat… Three hours after breakfast, we started a hunt for a set of playing cards to play cribbage. I asked the hotel manager if we could borrow cards from the hotel, or any other game that would keep us busy a few hours, days, a week. He pointed out a souvenir store where we could buy such items. Well, despite knowing that one should take his passport to the field, we did not have money. The hotel manager had a swift idea: “That’s not a problem, you can wash dishes after lunch.” Good times! So, we registered for being the little hands in the kitchen. The next 15 minutes were funny, I was trying to explain this to Clem, and to convince him that it was no joke at all. After lunch, we would be on dish wash duty, dressed in long underwear, and without glasses.

I left for a minute to go back to the room and heard Clem running toward me: “Dress up, we are leaving! The helicopter will take off within the next hour. We must go the airport right now.” Ha, ha, funny Clem, you thought I was joking with washing the dishes, and now you feel the need to make a joke too, but I ain’t a silly fool, and it’s not April 1st yet. Well, when I saw Clem dressing up, and tightening his shoes in a hurry without wasting time to comment further on his statement, let me tell you, I quickly dressed up too! I could not risk missing that flight, if it happened.

Air Greenland was able to fly us back to Kulusuk using a French-made helicopter (an Ecureuil – an Astar helicopter) flown by an Icelandic pilot. Certainly, he was used to windy conditions, and low visibility. We were reunited with Rick for lunch in Kulusuk!

We would like to thank Air Greenland for their dedication to serving our project yesterday and today. Working with us on a flexible schedule to get the cargo flight in yesterday was a big help. Accommodating us in Tasiilaq and getting us back to Kulusuk this morning allowed us to be ready for the next opportunity to fly to the ice sheet so we can begin our experiments. A continued good relationship with Air Greenland and their pilots is important for the success of our science. We view them as team members critically needed to move forward with a successful campaign.