By Clément Miège

Kulusuk, 26 March 2014 — “Opa” is a Greenlandic word for “maybe”, as we learned it this morning while talking to Danish guests at the hotel Kulusuk who have been stuck for a few days due to bad weather.

To give you a little bit of background, the southeastern part of Greenland witnesses the highest precipitation rates of the island, in conjunction with strong winds (either from the ocean or the ice sheet). Often, the weather is unpredictable, especially at this time of year. Therefore, conducting fieldwork in southeast Greenland is a gamble.

Last year, when we experience really great weather in Kulusuk the week before our field work, we did not fully realize how lucky we were to be able to go to the field as scheduled. This year, it has been a different story: we have already gone through two storm systems, and yesterday night a third storm hit us, with a lot of wind and snow. We feel like we are paying the price of last year’s fantastic weather.

That being said, this weather is good to prepare the cargo for our flights to the ice sheet. We spent a good part of Sunday getting the low-frequency radar system ready. We worked on the radar sleds, as well as on the tube that will keep the radar antenna straight when we drag the system on the snow surface.

Ludo and Clem, working on gluing the coupling made to connect the radar antenna tubes. (Credit: Rick Foster.)

On Monday, we went to the village of Kulusuk to buy some supplies (we are currently staying in a hotel that is about a 30-minute walk from the village). On our way to the village, we saw four teams of dog sleds ready to leave for Apusiaajik glacier. The dog sleds are carrying skiers and a week-worth of their base camp materials, so the skiers can enjoy the fresh snow!

We walked around the village to get some nice views of the ocean and the sea ice. As we were walking, Ludo made a local friend! A Greenlandic kid who was a really fun guide and gave us a tour for an hour. At some point, we realized that he was always avoiding the direction of the school!

Rick in front of the broken and refrozen sea ice. Imagine how different it is from the open ocean in the summer, with boats cruising around. (Credit: Clément Miège.)

After that, we went to the store and got some food and a propane tank for our stove on the ice sheet. We found everything we needed and headed back to the hotel. We finished the day at the airport further organizing the science equipment.

Rick works on an extension of the ARGOS antenna mast that we already have installed in the field. (Credit: Clément Miège.)

Tuesday, Ludo and I went back to the airport warehouse and finished organizing the cargo for the helicopter flights. We’ve prepared two distinct: one consists of our camp gear, sleep kits, food, personal gear, and some science equipment. The other (which can arrive later), is composed by the rest of the science gear.

Wednesday has been different, and we thought it would be “fun” to walk you through the steps that we have gone through today in terms of decision-making:

In the morning, Thursday’s flight is still ‘opa’. We are optimist and getting ready to leave, packing personal bags and organizing the last bits of equipment.

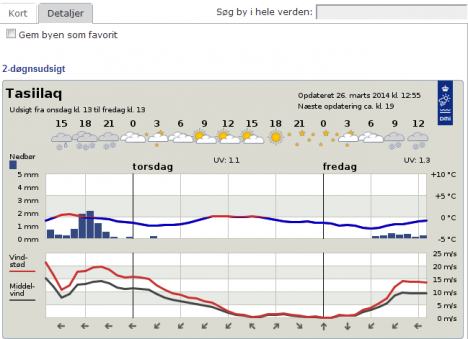

Weather forecast, from the Danish Meteorological Institute, for today Wednesday (March 26) and Thursday (March 27). The good weather window is for Thursday.

2 pm: The weather is not improving much and we start wondering if we will still be able to leave tomorrow. According to the forecast, a break in the storm system is still possible for tomorrow, but we would need it to last for at least a couple of hours, so that we can have one or two helicopter rotations from Kulusuk to our camp on the ice sheet. Each helicopter rotation takes about 2 hours.

3:15 pm: We receive an email from our project manager, based in the US. The helicopter company (Air Greenland) advises us not to leave for the ice sheet tomorrow since an extreme storm is coming for the next days and our team will be incapacitated (meaning that we will not be able to leave the tent for four to six days). This email is worrying us further, and we do not need to be trapped in a tent on the ice sheet without being able to do any work. It is a difficult decision to make, since the weather will be good tomorrow. Moreover, if we leave, we would be able to start working as soon as the storm passed and not be risk further delays in getting to camp, since the helicopter might be needed for other important duties, like resupplying villages. We have to balance the pros and cons — put simply, we have to balance spending four to six days in a tent doing nothing but trying to stay warm vs. gaining about half a day of work, since that way we would not need to wait for our put-in flight. After an intense discussion involving our partners and the weather office, we finally decide that we will not fly tomorrow.

Left: Rick, calling with the satellite phone, using a homemade extended antenna (credit: Ludo). Right: Ludo and Rick waiting to hear back from Air Greenland about tomorrow’s flight. (Credit: Clément Miège.)

4 pm: Our flight for tomorrow is officially canceled.

7 pm: Even if it does not make any sense to have a passenger flight tomorrow due to this upcoming weather system, we think that it will be really valuable to have a cargo flight to drop our equipment. Hence, only one helicopter load will still need to be transported when the storm is over. We’re still working on this option.

We are not sure when we will be flying, but at least we are ready. Please keep your fingers crossed for some good weather. More updates soon, opa!

All the best from snowy Kulusuk!

At approximately 60° South and 174° East the FSG members sampled their first official station of the field campaign. The solid red line in the map below denotes the current ship track (as of March 27th). The ship has not yet reached the P16S line that begins at 150° West (the blue circles on the map below).

The FSG will deploy an IOP package at one station each day. The FSG IOP package is an assemblage of instruments that collect data for temperature, salinity, depth, absorption of particles and dissolved components, and particle scattering. The instruments are contained within a metal ‘cage’ that is lowered on a wire to a chosen depth in the water column. The data collected by the instruments are saved to a type of hard drive located within the cage. Before the cage can be deployed, weight must be added so that it can sink.

Here, the cage with all of the instruments is being lifted off the deck of the ship and lowered into the water.

And, sometimes, King Neptune decides to send a wave your way. But that is why we wear our safety gear!

The FSG also collects surface water samples in conjunction with the IOP package deployment. A weighted tube is lowered over the side of the ship, and a large peristaltic pump gently transfers seawater to a large container (carboy).

The water is filtered and processed back in the laboratory on the ship.

Now, let’s take a moment to understand the significance and importance of hydrographic field campaigns. Oceanic and atmospheric processes are tightly coupled. Temperature and freshwater fluxes between the ocean and atmosphere are in control of climate variability. A good example of this strong ocean-atmosphere relationship is El Nino Southern Oscillation or ENSO. During an El Nino event, the temperature structure of the equatorial Pacific Ocean is disrupted. The central equatorial Pacific Ocean becomes warmer than normal affecting tropical rainfall in Indonesia and global weather patterns. The objective of the Climate Variability and Predictability of the ocean-atmosphere system, or CLIVAR, program is to understand this dynamic coupling and model future ocean-atmosphere variability by collecting and analyzing ship-based global observations. The International CLIVAR program is a continuation of its predecessors: the Tropical-Ocean Global Atmosphere (TOGA) and the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE). The TOGA program was formed in 1985 to study the relationship between the tropical ocean and the global atmosphere with the ultimate goal of predicting variability on various time scales. The WOCE program began in 1990 with the objective to study global ocean circulation and its relationship to the global climate system over long time scales using global observations. The US-CLIVAR program contributes to the international program as well as the World Climate Research Program. You can learn more about the US-CLIVAR program here.

The guys are finally on their way! The R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer set sail from Hobart, Tasmania on March 20, 2014 ( GMT +11 hours). The science party is made up of a total 29 scientists, 9 of which are graduate students. The first Go-SHIP station is located at 67°S, 150°W. While in transit, scientists will deploy the first Bio-Argo float of the campaign, 6 days from sail. An Argo float is a battery-operated, autonomous float that can move up and down the water column collecting temperature and salinity profiles up to a 2000m depth by pumping fluid into and out of a bladder to manipulate buoyancy. A Bio-Argo can collect measurements of chlorophyll-a and backscattering, in addition to salinity and temperature profiles. The deployment of Bio-Argo floats is particularly important for validating ocean color remote sensing data. For more information about Argo floats, you can proceed to the following links:

Setting up a scientific laboratory on a ship is no easy task. Space is usually limited and you must be able to play well with others. We have filtration equipment (the large wooden frames) set up to collect the biogeochemical parameters, i.e. phytoplankton pigments, particulate organic carbon and particle absorption. The parameters are collected onto small paper filters and frozen for future analyses back at NASA Goddard. We also have two instruments set up on board to measure colored dissolved organic matter (CDOM), which is like tea, compounds extracted from plant material that can flow out into the ocean via rivers. While in transit to the first station Mike, Joaquin and Scott are busy collecting samples.

A major addition to this year’s field campaign is a ‘souped-up’ underway-sampling system built by none other than Scott Freeman, our optics expert on board the Palmer. The set-up contains multiple instruments that collect dissolved and particulate absorption, CDOM fluorometry, chlorophyll and particle scattering at 660nm. The system is connected to the ship’s seawater system that pumps clean seawater from <10m depth through the ship and then to faucets at which the water can be accessed. The term ‘clean’ means the plumbing that facilitates seawater pumping to the laboratories is routinely checked for clogs and algae growth.

Lastly, a blog post isn’t complete without a gratuitous photo of macrofauna. Here is a photo of a petrel taken by Joaquin Chaves. Can anyone identify what kind of petrel this is?

By Clément Miège

YAY! We made it to Kulusuk on Saturday afternoon! It ended being a not-too-long journey, since all of our flights were on time.

Rick, Ludo and I followed different itineraries. Rick left Salt Lake City on Friday morning and a red-eye flight took him to Keflavik International Airport in Iceland. He landed early Saturday and took a bus from the international airport to the domestic airport in Reykjavik (an hour-long ride).

Ludo came from a meeting in Switzerland and arrived in Iceland late Friday night. He stayed at a nearby hostel in Keflavik. The next day, he was told to take a bus that would take him to the domestic airport and that supposedly departs every hour in the morning. After waiting for a while, with no bus in sight, he walked back to town (carrying 2 duffel bags, a ski bag, and 2 carry-on bags) and learned his first Icelandic words: Saturday and Sunday (laugardaga og sunnudaga.) Turns out, during the weekend, the bus schedule is different. Good thing that taxis were not too far and that he ended up making it on time for his 12:45 pm Greenland flight!

Me, I had a one-day layover in Reykjavik, which was a nice chance to rest a bit and quickly visit the city. I walked around town, not for too long because it was definitely cold and windy and I am not yet acclimated to cold temperatures — but I will be in the next few days!

Reykjavik is a nice city… when it’s not too windy. The day I arrived, the wind was gusting and it was just too cold. But I still went on a walk to check the Hallgrímskirkja church. This is the largest church in Iceland, an amazing structure! Inside, there is a lift, making the church a pretty sweet observation tower with nice views over the city.

[Note: Originally in this post, I erroneously said Halgrímskirja is a cathedral. Thanks to our reader Harry McKone for spotting the mistake!]

On the left, the church with the statue of Icelandic explorer Leif Eriksson. This story explains the first discovery of North America by a Viking expedition, led by Leif Eriksson about 500 years before Columbus: http://www.history.com/news/the-viking-explorer-who-beat-columbus-to-america. On the right, downtown Reykjavik, composed of colorful houses. (Credit: Clément Miège)

The next day, I joined Ludo and Rick at the domestic airport (they both arrived before me). Useless to say that we had a lot of gear between the 3 of us, a total of 6 carry-on bags (including laptops, radar computer, transmitters, GPS, etc.), 5 checked bags (with our cold weather gear), and 2 ski bags. We were a bit scared at first by Air Iceland’s policy of only allowing one 5kg carry-on and a 20kg checked bag per person, but we ended up getting through easily, which was a relief!

The flight was smooth and fast, only 2 hours to get to Greenland. Approaching Greenland, we started to see more and more winter sea ice along with some big icebergs trapped within it, which is always very pretty. The first islands finally appeared and we were about to land on one of them, where the little town of Kulusuk is.

Interestingly, the sea ice in the fjord next to Kulusuk seemed weaker and it might be thinner this year than when we visited last year. Ludo noticed some spots that were already ice free (see the photo below); those spots were covered by sea ice last April. The wind redistribution of the sea ice and the warm temperature in Kulusuk in January might be the reasons for this weaker sea ice pack.

View from the plane of the sea ice around Kulusuk (the little black dots are houses.) (Credit: Ludovic Brucker)

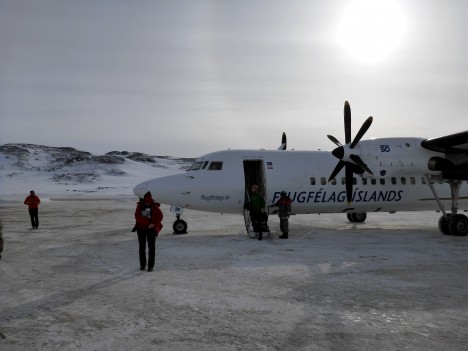

Our plane, freshly landed at the Kulusuk airport, with a faint sun halo in the background. (Credit: Rick Foster)

Shortly after landing, we made it to our hotel, and started to unpack. This year, Ludo and I brought back country skis, which is a really nice and fun improvement, and also a faster way to get from the hotel to the airport, or to go to the old garage where some equipment is stored from last year.

At the airport warehouse, we found all the equipment that we sent from the U.S. We counted the boxes and, great news, everything had made it her, and was in pretty good shape too! We started to unpack some items and took some of them to the hotel for re-organizing them some more.

At the Kulusuk airport, Ludo moves equipment around to consolidate our cargo (left). Some equipment is ready to be loaded on the helicopter (right) to go to our field site, but other gear needs some repacking, which will be one of our main tasks for the coming days. (Credit: Clément Miège.)

Today, a big storm is here and it’s a white-out outside — crazy, brrrrr! It is snowing horizontally. So happy we are not in the field right now! It is really windy this morning, about 37 mph, so we have decided to work indoors. We have couple projects: preparing antenna tubing for the low-frequency radar, preparing the radar sleds, assembling the ARGOS antenna pole, and starting to pull out the equipment from our last year’s storage place.

I can’t take any photos today, since it’s just white everywhere and impossible to see the surrounding buildings.

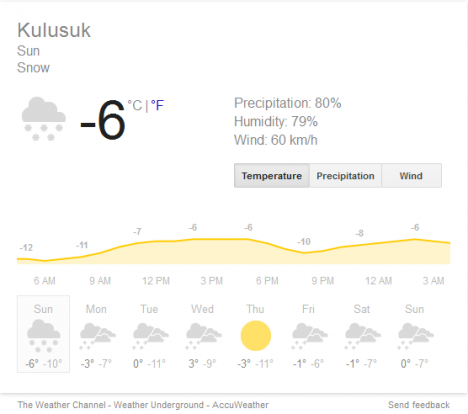

We are still on track for leaving this Thursday (March 27) to go to our camp site on the ice sheet. Amazingly, the only day of the week that looks good for flying out is Thursday — see the forecast below. That is lucky for us!

According to the Weather Channel, the only day with good weather this week is Thursday — good thing we are scheduled to leave then!

I’ll send a new blog post in a few days, stay tuned!

Three members of the Ocean Ecology Laboratory’s Field Support Group (FSG; Code 616) will embark on a 45-day journey from Hobart, Tasmania to Papeete, Tahiti on the icebreaker R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer (NBP). The field campaign is part of the US Repeat Hydrography, P16S, 2014 under the auspices of GO-SHIP and sponsored by the US Climate Variability and Predictability Program (CLIVAR). You can find more information about the program here. The FSG will collect biogeochemical samples and bio-optical data across the South Pacific. These data will eventually be ingested into NASA’s SeaWiFS Bio-optical Archive and Storage System (SeaBASS) and subsequently used for ocean color satellite validation activities.

During the next six weeks, I will be helping my colleagues chronicle their journey over the high seas. They will share not only information about the science but also describe the daily life of a sea-going scientist. I, too, participate in many of these campaigns and am very familiar with the NBP having sailed on it three times during my career. Alas, I could not participate in the journey so must live vicariously through my colleagues. Below, you will find the biographies of the three NASA scientists that are participating on this cruise: Joaquin Chaves, Scott Freeman, and Mike Novak. You can also follow the ship track here.

Joaquin Chaves, received his PhD in oceanography from the University of Rhode Island in 2004. For his graduate work he conducted research on estuarine biogeochemistry. He held postdoctoral positions at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA, and at Brown University, in RI, where he focused on the biogeochemistry of land use change in tropical forests, particularly in the Amazon region. He’s been a contract scientist at NASA-GSFC since 2009, where he has focused on ocean color satellite remote sensing and marine bio-optics. He has participated in ocean-going field campaigns to the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic Oceans, as well as the East China Sea.

A native Californian, Scott Freeman grew up in Salinas, near the Monterey Bay, and attended the University of California, San Diego. After a lengthy hiatus in New York City, he returned to college and received a B.S. in Biology from the City University of New York. He then attended the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography, completed a master’s degree, and stayed in Rhode Island to work first for the URI, and then for Wetlabs, a manufacturer of oceanographic optical instruments. While in Rhode Island, he participated in many cruises and coastal exercises, including NASA’s Southern Ocean Gas Exchange Experiment (SO GASEX) and ONR’s Radiance in a Dynamic Ocean experiments (RADYO).

Since joining SSAI in 2011, Scott has participated in several field campaigns for NASA’s Ocean Ecology Laboratory, and is responsible for AOP and IOP data collection and processing. He lives in Alexandria, VA with his wife Heidi and sons Charles and Adrian. When not engaged in field research, one can find him playing bass for the Washington Metropolitan Philharmonic Orchestra.

Mike Novak grew up in Piscataway, New Jersey, about 30 miles southwest of Newark. After graduating high school he attended the Richard Stockton College of New Jersey where he earned a B.S. degree in marine science. After college, he attended graduate school at the University of New Hampshire where he earned an M.S. degree in Oceanography. He worked as a researcher at UNH before relocating to the Washington D.C. area where he now works as an oceanographic researcher at NASA-GSFC. When he is not sailing the high seas, he is also an avid musician playing at various venues around the D.C. area with his band Novakaine.