By Clément Miège

Hi there! I am Clément Miège, a Ph.D. student at the University of Utah and I am going to take you along with us to our second expedition to the southeast region of Greenland, to investigate the physical properties of a firn aquifer. And what is a firn aquifer, you might be wondering? It’s a reservoir of perennial water (that is, water that doesn’t freeze in the winter) that is trapped within the compacted snow layer (or firn) of the Greenland ice sheet. If you didn’t follow last year’s edition of this expedition and/or you want to learn more about the firn aquifer, here are some readings I recommend:

We are now getting ready for another expedition to Greenland to further monitor the firn aquifer. This year, our four main tasks will be to maintain our equipment currently in place (which performs temperature measurements), collect additional measurements (with a radar), install a weather station, and try traditional ground-water techniques to date the water and calculate its permeability. I will explain in future blog posts why these measurements are important.

I will be part of a smaller team this year, since only three out of the five members of the first-year team are joining. Rick Forster and I will represent the University of Utah, while Ludovic Brucker comes from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

Here is the photo of the team from last year, from left to right; Jay, Ludo, Rick, Lora and I. Lora and Jay won’t be coming to the field this year (we sure will miss them!) If you want to know a bit more about each team member (current and former), you can check this blog post from last year.

Even when we haven’t set a foot in the field yet, the expedition to Greenland started about two months ago with organizing the logistics. Logistics can sometimes be underestimated, but it takes a lot of effort prior to getting to the field to prepare and test the scientific equipment and other field supplies, such as camping gear, food, and power sources.

For this expedition, all of the science equipment (GPS, radars with different frequencies — 5MHz to 400MHz–, piezometers, ice-core drill) was gathered from different institutions in Utah to be packed here and shipped to Kulusuk. Most of the non-perishable food and camping gear was left for over-winter storage after last year’s expedition in a warehouse in Kulusuk, to save on shipping costs.

On March 3 this year, the Utah gear left for Greenland; we’re talking about 800 lbs. of gear that left Salt Lake City on a truck headed to the JFK airport in New York, where it was flown to Reykjavik (Iceland) and then to Kulusuk (Greenland). We got a phone call early this week from our shipping company to confirm that all our equipment made it to Greenland — great news!

Gear packed at the office (left) and ready to leave the shipping facility at the University of Utah (right). We will see this gear again in Greenland!

These last days have been really busy, gathering the last items for our science research, and also personal equipment. Yesterday, I was working at Blue System Integration in Vancouver, BC with a colleague, Laurent Mingo, who is developing IceRadar, an ice-penetrating radar system for the scientific community (see this website for additional info). Laurent has been working on an experimental beta version of the current radar that will allow us to penetrate through the firn aquifer to try to image the bottom of the aquifer gradually transitioning from water-saturated firn to ice.

Even if most of the scientific equipment is already shipped, there are always some last-minute important items that we end up adding into our suitcases (like the low-frequency radar). As a brief anecdote, last year, Rick traveled with a pelican case as a checked bag – inside, there was a bunch of wires hooked up to a datalogger. We were aware that it looked kind of suspicious, so it was a bit scary to go through customs with it! Me, I traveled with a 60-meter long thermistor string weighing over 50 lbs. in my checked bag, because the fabrication and calibration took longer than expected and we weren’t able to ship it ahead of time with the rest of the equipment. This year, luckily, most of the heavy equipment was ready on time and we are carrying only a couple random items in our checked bags.

We are starting our journey this week, leaving the U.S. on Thursday evening for Reykjavik, the capital of Iceland. After a day in Reykjavik, we will leave mid-Saturday on a 2-hour short flight that will take us to Kulusuk, Greenland. We are hoping for good weather; last year, Ludo and I “boomeranged” on our first try due to poor visibility at the Kulusuk runway.

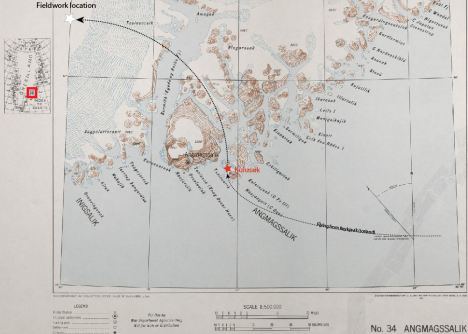

In this old map from the US army (from 1941) you can see the location of the small city of Kulusuk in Southeast Greenland (red star), just below the Arctic Circle (~66.5°N). Our field camp on the ice sheet is represented by a white star. The map can be found at the Polar Geospatial Center.

Kulusuk is our first stop in Greenland. We will be staying at this small village for a few days in order to re-pack our field gear, test that everything is working well (stoves, generators, tents, science equipment, etc.) before going to the field. If we are lucky, we might see one of the polar bears that sometimes come close to town in this time of year.

Colorful houses make up the town of Kulusuk in Southeast Greenland. The shores of the fjord are covered by sea ice in the winter.

After a couple of days, we will be heading to our fieldwork location on the ice sheet. A helicopter from Air Greenland will drop us and our cargo at our study site; it will be an about 45-minute commute.

That is it for this introduction; our next blog post will be from Greenland!

All the best,

Clément

Every mission has its little offerings to fate to back up the hard work and attention to detail that goes into prepping for launch. While in Japan, the GPM team adopted the Japanese custom of coloring in one eye of a Daruma doll.

I first encountered it when visiting the support control room for the launch dress rehearsal last weekend in the Spacecraft Test and Assembly building at Tanegashima Space Center. Sitting on top of one of the computers was a round, squat, stylized doll. Lisa Bartusek, one of the systems engineers on console for the rehearsal, explained that in Japan, the Daruma doll is often given as a gift of encouragement for working toward a goal. When the goal is set, one eye is colored in. When the goal is achieved, the second eye is colored in.

A Daruma doll is seen amongst the NASA GPM Mission launch team in the Spacecraft Test and Assembly Building 2 (STA2) during the all-day launch simulation for the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Core Observatory, Saturday, Feb. 22, 2014, Tanegashima Space Center (TNSC), Tanegashima Island, Japan. Credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls

My reaction to seeing it was that it would definitely motivate me to finish a goal: a doll with only one eye filled in, looking lopsided, would drive me nuts.

The GPM team has several Daruma dolls. The one for the team on console in Tanegashima was for a safe and successful launch. Back at Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. a second and third Daruma doll sat in the Launch Support Room (LSR) and the Mission Operations Center where the GPM team is runs the mission now that the GPM Core Observatory is in space. For the Goddard team, their goal was to have the GPM Core Observatory separate from the rocket, get communications running, deploy solar arrays and point toward the sun to collect power. Those were the big moments for the team in the hot seat.

Caitlin Bacha on the GPM propulsion team was on console in the LSR at Goddard and wrote to me a few hours after launch. “Wahoo! Success!! I also think it’s funny how many videos have all the cheering after the rocket goes up. In here it was silent. The cheers came 10 min after with acquisition of signal. And again with the solar arrays deployed. Since then it’s been a flurry of activity in the LSR!”

JAXA has a daruma doll, too. One is seen on the desk of Masahiro Kojima, GPM Dual-frequency Precipitation Radar project manager, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), at the Tanegashima Space Cener’s Range Control Center (RCC), Wednesday, Feb. 26, 2014, Tanegashima, Japan.

After GPM’s successful launch at 3:37 a.m. (JST) on Friday, Feb 28, the team started coloring in the eyes.

The colored in eye of the Daruma doll in the Tanegashima launch support room, Feb 28 (post-launch JST). Credit: Cody Buell

The Daruma doll in the Mission Operations Center at Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, the eye colored in post-solar array deploy, Feb 27 (post-launch U.S. EST). Credit: Eish Patel

Larry Morgan, quality assurance, fills in the eye of the Daruma doll on the back of a MHI engineer’s t-shirt, Feb 28, Tanegashima, Japan. Credit: Lynette Marbley

Art Azarbarzin, GPM project manager, fills in the second eye of the JAXA Daruma doll at the party after launch with JAXA engineer Hyakusoku Yasutoshi, Feb 28. Credit: Lynette Marbley

The only one still uncolored is the one in launch support room at Goddard. When I asked for photos after launch, Lisa wrote me that the team at Goddard has extended their goal to include powering up the instruments. The GPM Microwave Imager was turned on Mar. 1. The Dual-frequency Precipitation Radar had its controller turned on as well, and full power-up is scheduled for later in the week.