By Christine Dow

Credit: NASA/Christine Dow

The big day had arrived. We were due to fly to our tiltmeters to collect the data that they had been gathering for two weeks. once this was the first time we had ever set these instruments up in the field, all fingers were crossed that we had been precise enough in initially leveling the meters so the data were in range and also that the solar panels hadn’t ended up covered in snow.

We had a spectacular flight, cutting over the end of Priestley Glacier and skirting helicopter-sized crevasses on the mountain behind our field site. Despite a bit of wind on the Nansen ice shelf, it was as calm on the Comein Glacier as it has always been for our visits. It’s such a peaceful, sheltered spot that I feel a holiday cottage wouldn’t be amiss. Perhaps too long of a commute for an average Friday afternoon, however.

Credit: NASA/Christine Dow

One of the tiltmeters (which are in black boxes) had become exposed and, because black materials absorb heat whereas white materials reflect it, had caused a bit of local melt which had trickled down the side of the box and refrozen. The upshot of this was that the entire box, battery, and straps were encased in some pretty solid ice. Fun! Commence some delicate hacking with ice axes so that we didn’t snap the wires coming out of the box. Finally having reached the interior, we nervously extracted the SD card and Ryan pulled the data off onto the computer. Success! Some excellent (and exciting) looking data showing tidal cycles. Tiltmeter two was easier because it hadn’t caused local melt of the snow so we could quickly retrieve the data. Again, some very interesting outputs. We want to thank John Leeman, an engineer from Penn State, for building us some happily working tiltmeters. Of course having disturbed the tiltmeters I had to reset them back to full level, which required sitting for 10 minutes enjoying the view while very delicately adjusting the little leveling legs.

We had just enough time to collect data from one of the GPS closest to the tiltmeters. All looked well apart from our tethers, which had come loose because of melt on the surface. We had one bamboo tether and one metal peg. The metal had heated up and melted a groove in the ice as it was pulled along, whereas the bamboo had stayed where it was supposed to. We tightened the wire as much as possible but we would have to return to this site with some more bamboo later.

Credit: NASA/Christine Dow

Dinner back at base was a happy affair, having achieved success for at least three of seven of our instruments. The chefs had even made some pizza for us, which was a nice treat. The only unfortunate aspect of the day was that I had forgotten that in areas with 24 hour sunshine and highly reflective snow surfaces it is essential to put sunscreen up your nose as well as on it. Burnt nostrils are not fun, but they’re worth it for some nice data.

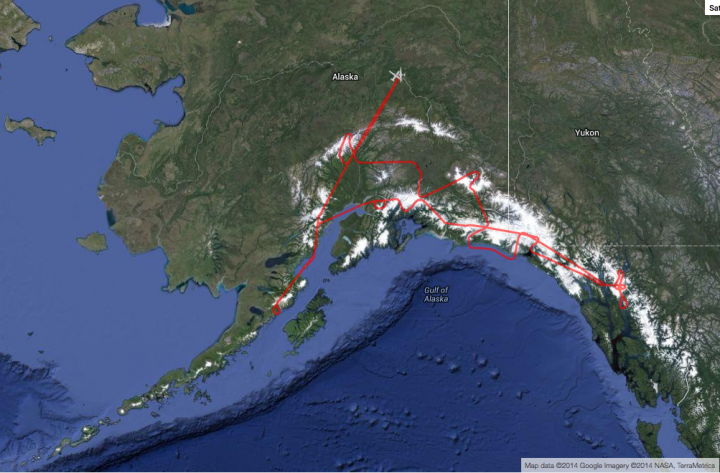

For more than 65 hours this month, NASA’s high-altitude ER-2 aircraft flew from Fairbanks over melting sea ice, glaciers, forests, permafrost, lakes, volcanoes and more. It zigged and zagged over the Beaufort Sea, and soared straight over the Bagley Ice Field.

The goal: to use a laser altimeter called MABEL to take elevation measurements over specific points and paths of land, sea and ice. To hit these marks, scientists and pilots painstakingly designed and refined flight routes. And then they adjusted those routes again to capture cloud-free views – a tricky proposition in a giant state with mountains creating complex weather systems.

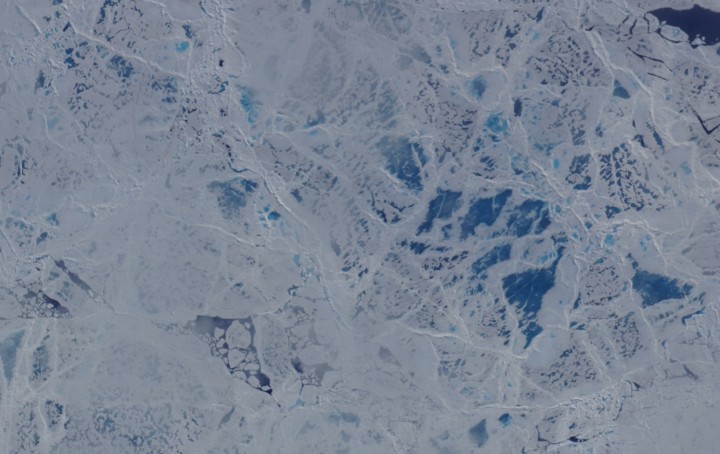

A camera on the MABEL instrument captured pictures of cracked sea ice, dotted with melt ponds, during a flight to the North Pole. (Credit: NASA)

“We have targets to the north, targets to the south, and mountain ranges blocking both,” said Kelly Brunt, a research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center who was MABEL’s science flight planner.

Scientists studying forests, glaciers, water and more are using MABEL data to develop software programs for the upcoming ICESat-2 satellite mission, and sent Brunt lists of what they would like to be included in the Alaska campaign.

“We get everybody’s input, and start to put it on a map,” she said. She drafts routes with targets in similar weather patterns, so that if one is clear the others are likely to be as well. However, often targets are removed from a route, based on the weather assessment from the morning of the flight. During the deployment, routes are also constructed to target specific sites that were missed during previous flights for either weather or aircraft reasons. Lots of the work goes into straightening the flight line, Brunt said, since when the aircraft banks at 65,000 feet, the laser instruments swivel off their ground track and the scientists can lose miles worth of measurements.

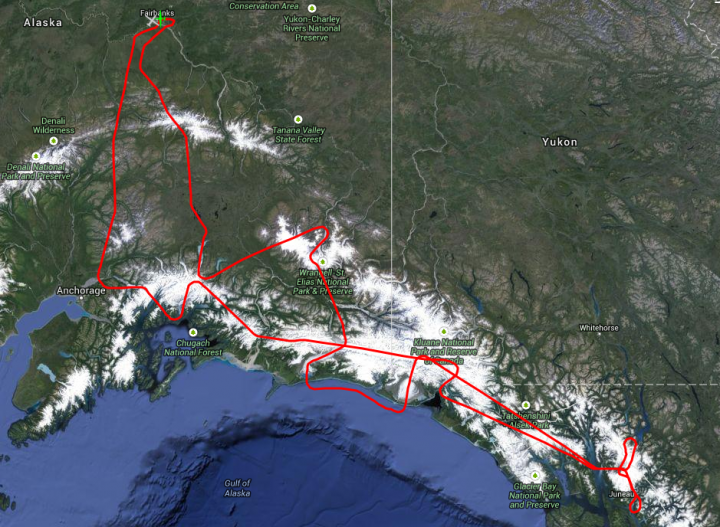

The MABEL campaign’s July 24 flight route covered glaciers, ice fields, forests, the Gulf of Alaska and more. (Credit: NASA)

One flight to measure sea ice was pretty direct – it took the pilot straight to the North Pole over one longitude line, circled around and came back on another. A second route involved a zig-zag pattern over the Arctic. But both routes were designed to capture a range of summer ice conditions, including melt ponds, large stretches of open water, and small openings in the sea ice, known as leads.

Flights over Alaska itself were often mapped to pass over glaciers, lakes, ocean moorings or even tide gauges that others have measured before, to compare with the data MABEL collected. Students from the Juneau Icefield Research Program (JIRP) assisted MABEL researchers by providing ground-based GPS validation for a mission that flew over the upper Taku Glacier, close to a JIRP camp. And the MABEL team collaborated with NASA Goddard scientists flying a different instrument, called Goddard’s LiDAR, Hyperspectral and Thermal (G-LiHT) Airborne Imager – the two campaigns flew some of the same paths over interior Alaskan forests.

NASA ER-2 pilot Denis Steele, in a pressurized flight suit, before a July 16 flight over Alaska’s glaciers. (Credit: Kate Ramsayer/NASA)

From Fairbanks, Brunt worked with the campaign’s two pilots, Tim Williams and Denis Steele, to ensure the routes would work with the ER-2’s capabilities; and with weather forecasters to determine where to best focus efforts the following day.

In all, the campaign flew 7 flights out of Fairbanks. And today, the ER-2 – with MABEL aboard – flies back to California, collecting even more data about the elevation of the landscape along the way.

I didn’t know a hybrid sedan could take a corner that fast. We were sitting in the car, adjacent to the runway where NASA’s ER-2 high-altitude aircraft was about to land. Tim Williams – an ER-2 pilot who will fly later this campaign – was driving, poised to speed down the runway after the plane, in case his fellow pilot needed help avoiding obstacles and gauging conditions.

And as soon as the sleek ER-2 came into view and descended over the runway, we were off. Williams hit the gas (battery?) on the hybrid and swung onto the runway, sending me and my video camera flailing against the passenger-side door as the aircraft buzzed overhead. We raced down the runway, chasing after the plane as it landed, balanced on its two wheels.

On board the ER-2 is MABEL – the Multiple Altimeter Beam Experimental Lidar – a laser altimeter that is gathering data for the ICESat-2 mission. Wednesday’s flight was the first science flight of MABEL’s summer campaign to measure summer sea ice, land ice and more in Alaska.

The day started with a crew and weather briefing at 7 a.m., where pilots Denis Steele and Williams reviewed weather conditions and possible routes with ER-2 Mission Manager Tim Moes, NASA Goddard scientists Thorsten Markus and Kelly Brunt, weather forecasters and others.

With cloudy conditions on the way to the North Pole – covering the dynamic melting edge of the sea ice the campaign hopes to document – the team decided to head southeast out of Fairbanks. That route heads down to the Alaska Peninsula to survey volcanoes, then heads east over glaciers and high-elevation ice fields in south central to southeastern Alaska.

The ER-2, with MABEL on board, flew over volcanoes and glaciers in south central and southeastern Alaska. (http://airbornescience.nasa.gov/tracker/)

With the flight route set, scientists made final checks of the instruments and Steele put on a pressurized suit – necessary for flying at 65,000 feet. He has to “pre-breathe” pure oxygen for an hour before flight, to raise his blood oxygen level.

Ryan Ragsdale, engineering technician, helps ER-2 pilot Denis Steele put on a pressurized suit before the flight, which will take him to 65,000 feet. (Credit: Valerie Casasanto/NASA)

Meanwhile, the plane was slowly towed out of the hangar onto the runway at Fort Wainwright and fueled up. The ER-2 crew and Williams went through the preflight checklist, which would be difficult for Steele as the pressurized suit has big gloves and limited dexterity.

ER-2s Denis Steele, in the cockpit, and Tim Williams, checking notes, get ready for the day’s flight. (Credit: Kate Ramsayer/NASA)

After Steele got in and started the engines, he taxied to the end of the runway accompanied by a maintenance van and a chase car: the van so that the crew could grab the bright orange stabilizing wheels, which fall off during takeoff, and the chase car driven by Williams, who supports Steele as necessary.

The ER-2 takes off amazingly fast. One moment it’s at the end of the runway, the next, the roar of the engine sounds. Then, all of a sudden, the aircraft’s in the air, climbing fast to the clouds. The plane disappeared into the clouds before the sound faded, and then the team went back to check the instruments’ vital signs, transmitted from flight.

Just under seven hours later, after flying over a number of key glacier and volcano points north of the Gulf of Alaska, Steele landed the plane. The crew reattached the bright orange stabilizing wheels, and towed him back to the hangar, where scientists were eager to download and view the data.

Steele reported on highlights of the flight – what was cloudy, what was clear – and Moes ended with a reminder of the next early morning meeting to review weather conditions and determine whether the ER-2 would fly another route over Alaska today.

Clouds blanketed much of MABEL’s potential flight routes over the Alaskan Arctic or southern glaciers on Monday, so the ER-2 aircraft stayed in the hangar at Fort Wainwright in Fairbanks, Alaska.

But the MABEL team was busy. They took advantage of a day on the ground by improving the instrument’s new camera. The goal is to take more images like the one below, to help scientists interpret the data from the airborne lidar instrument.

As the ER-2 aircraft traveled from Palmdale, California, to Fairbanks, Alaska, the camera on MABEL took this shot of wind turbines near Bakersfield, California. (Credit: NASA)

It’s the first week of the summer 2014 campaign for MABEL, or the Multiple Altimeter Beam Experimental Lidar, the ICESat-2 satellite’s airborne test instrument. MABEL measures the height of Earth below using lasers and photon-counting devices. This year, the team is using a new camera system to take snapshots of the land, ice and water in parallel with MABEL’s measurements.

The MABEL instrument is nestled snug in the nose cone of the high-altitude ER-2, which has a circular window in the base where the laser and the camera view the ground. To get access to MABEL and the camera, the crew propped up the nose and wheeled it away from the aircraft.

The ER-2 crew rolls the aircraft’s nose — containing MABEL — away from its body, so engineers could work on the instrument. (Credit: Kate Ramsayer/NASA)

The team then carefully slid the instrument out onto a cart, so that MABEL’s on-site engineer and programmer – Eugenia DeMarco and Dan Reed – could work on the camera and ensure the connections were sound.

MABEL engineer Eugenia DeMarco and programmer Dan Reed work on improving the new camera system for the instrument. (Credit: Kate Ramsayer/NASA)

When the camera was set to document the terrain from 65,000 feet, the team slid MABEL back to its spot and wheeled the aircraft’s nose back to the rest of its body. They connected the instrument to the plane’s electronics, sealed the plane back up, and are ready to go whenever the weather cooperates.

Luis Rios, with NASA’s ER-2 crew, checks the connections between the MABEL instrument and the aircraft. (Credit: Kate Ramsayer/NASA)

By Bob Bindschadler

Christchurch (New Zealand), 18 January — This will be my last entry in this season’s blog. I had hoped to tell a different tale the past two months —one of successful science being done in a harsh, remote place by hardy individuals dedicated to getting information that had direct relevance to your lives and the lives of others you know and will never know. But the field season unfolded in a vastly different way. I have prepared an outbrief for the National Science Foundation that speaks to the good and the bad, what went right and what went wrong, and how to use what was learned this season to improve our chances for success next season. That document is the official record and won’t be shared here, yet it contains no surprises from what you have read.

For this blog, I want to be more reflective and to emphasize those more personal aspects of Antarctic field work. It takes a lot of people working together to undertake a project as ambitious and as challenging as this one. This season, a lot of us involved in various aspects of this enterprise came together and grew to know each other a lot better. We did not always see things the same way, but I think just about everyone came away with a greater appreciation for what the project is all about and what talents each player has contributed to the greater enterprise. This was most apparent at PIG Main Camp where the great distance from McMurdo provided a clarity of purpose that often gets muddled in McMurdo. Following our limited success in the final days, I was impressed with how the Main Camp staff shared their congratulations with us. That success made their efforts at camp worthwhile. Our assistance in many of their camp chores showed them that we appreciated their efforts. That is the magic of a deep field camp. Even the Twin Otter pilots, who only dropped in for two days, felt good because we accomplished some objectives together.

I regret that the helicopters never came. I have little doubt the same camp magic would have occurred there, too. I question whether managers of the individual U.S. Antarctic Program components, who spend no time in the deep field, really understand how the deep field camps actually operate. There is a bonding motivated by the Antarctic environment that is much stronger in the deep field than in the more “civilized” McMurdo. Even large, multi-project camps can sometimes be absent of this mystic, but PIG is not of that ilk. You do not resent the person who has helped you set your tent, who you have helped shovel out a fuel bladder, who has watched you to make sure your nose is not frostbitten, and whose sled you have helped pull. The shared experiences bring people together and make for one. Every one of the camp staff expressed their hope to be chosen to come back next season.

As will we. We will succeed. Despite the limited scientific accomplishments this season, we are better positioned (with all the camp material, most of the scientific equipment and scads of fuel already at PIG Main Camp to spend the frigid winter) and logistically wiser to design a better field effort for 2012-13. We have to—it will be our last chance for this project. We’ll use satellite imagery to give us an early look next October. In November, Twin Otters will be used to assess the surface character of the ice shelf and to deliver a skeleton crew allowing us access to the wintered cargo, the fuel and to start on-site weather observations. By December, before the main camp even gets set up, the drilling team will arrive and will be transferred to the ice shelf with the drilling equipment by those same Twin Otters. Building the Main Camp and transferring the helos out will come later, much later if need be. Fewer Herc flights, earlier traverses and more Twin Otter time is a much more palatable recipe.

It saddens me to think that even today we should be working out of PIG Main Camp, making day trips to collect radar and seismic information on the shape of the ocean cavity beneath the ice shelf. Instead, our field team has disbanded. We flew to Christchurch together on Monday, but now we are scattering across the globe on various commercial airline flights. I’ve received word that the second traverse has arrived at PIG and this week there should be the final two flights pulling out the camp staff after they have put all the wintering cargo up on high snow berms. A recent satellite image taken last week shows the camp and the AWS webcam is still keeping watch from the ground. It looks like another beautiful day there.

I’m not exactly sure how to end this blog. I hoped you’ve enjoyed the story. I suppose I could just say that we now reenter the planning phase. There is yet more pressure on us now because we have one more shot to get it right. I think we will, but as always, the big unknown is what Antarctica has in store for us next time.