The recent megafire around Fort McMurray drew worldwide attention. Not only did this fire devastate a community, the fire also grew exceptionally large and started very early in the fire season. Northern forests are rapidly changing, and fire plays a crucial role in this transition.

A recently burned forest in Saskatchewan, Canada. (Credit: Sander Veraverbeke)

Fires in the boreal forest emit large amounts of carbon dioxide, the most important greenhouse gas. Exactly how much they emit is a difficult question to answer. Over many decades these forest have piled up thick layers of downed needles and other organic material, resulting in thick carbon-rich soils. When a fire spreads through the forest, the carbon it emits comes mostly from these soil layers, and not so much from the actual live trees.

The real question is: how deep do these fires burn into the soils? There is a lot a variability depending on which forest type is burning and how hot it burns.

Some members of our team just excavated a deep organic soil. They will carefully measure this soil pie and cut out some samples for lab analysis. (Credit: Veraverbeke)

As part of the ABoVE field campaign, our field crew flew into Saskatoon, Saskatchewan on May 28th from Massachusetts, California, Ontario, and the Netherlands. We joined up with another field team from the University of Saskatchewan. After stocking up on supplies, we drove about four hours north to enter vast swaths of boreal forest.

Our goal in Saskatchewan is to quantify how much carbon fires emit in forest types that currently burn infrequently, but may become more sensitive to fire in the near future. For example, we are interested in reburns in forests that last burned only a couple of years ago, or burns in forests where people previously cut down trees. With all the changes that are underway it is important to understand how fires impact these forest types and how much carbon they emit.

Our maneuvers in challenging terrain are rewarded by gorgeous vistas of landscapes that are untouched – except by fire. (Credit: Veraverbeke)

Since we arrived, we have been hitting up quite a few field plots. Getting to these field plots requires off-trail hiking in often-rough terrain, with soggy bogs and steep rocky hills. We have to scramble through piles of wood that fell down after the fire. Once we get to our desired site, we measure for several hours. We take samples of soils that will be analyzed in the lab and measure lots of trees (as many as several hundred). By doing so, we are able to assess the amount carbon of that was emitted by the fire.

We can link up our field measurements with data from NASA satellites to better characterize all fires within Canada and Alaska. During the day we get rewarded for our hard work with lunches-with-views, mosquitoes, and some thunderstorms that hopefully rain out somewhere far on the horizon…

Sander Veraverbeke is a project scientist at the University of California, Irvine, and an assistant professor in Remote Sensing at Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam

Our adventure began in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada on Wednesday, April 13th. After a solid day of driving up and over the Rocky Mountains, we arrived in Alberta on Thursday. Here are some photos from the drive. You can see our team mascot in the photos – a stuffed animal version of an American robin. His name is Chirpy, and we brought him along because Mrs. Christie-Blick’s 5th grade class at Cottage Lane Elementary asked us to. You can see that the kids even outfitted Chirpy with a pretend GPS unit and string harness.

Chirpy taking a rest on the shores of a lake near Jasper, AB. Photo credit: Natalie Boelman.

Chirpy in the car with Mt. Robson, British Columbia, Canada in the background. Photo credit: Natalie Boelman.

As Chirpy and I were posing in front of the Welcome to Alberta sign, some people in a car stopped and said they thought he was a real bird! Photo credit: Natalie Boelman.

Check out our field site & meet our team!

On Thursday evening around 8:30 pm, we arrived at our field site in the boreal forest, where we will catch and tag 30 American robins over the next week to ten days. We are working and collaborating with scientists at the Lesser Slave Lake Bird Observatory (LSLBO) and the Boreal Centre for Bird Conservation, which are located just north of the town of Slave Lake, Alberta.

Chirpy arriving at the Boreal Center for Bird Conservation (BCBC).

The Boreal Center for Bird Conservation (BCBC).

And, here’s a photo of our team. My Dad and I are on the far left. Willem is my super-handy Dad who has come along for the adventure and to help us with whatever we need help with – thanks Dad! Next to me are Ruthie and Brian, who are both graduate students at Columbia University in New York. Ruthie is working towards her PhD in Earth and Environmental Sciences at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, and Brian is working towards his PhD in Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Biology. Nicole – our resident bird banding expert – is on the far right. Nicole is a bird biologist who has been working at the LSLBO for almost ten years. She knows a whole lot about the birds here, and how best to catch them!

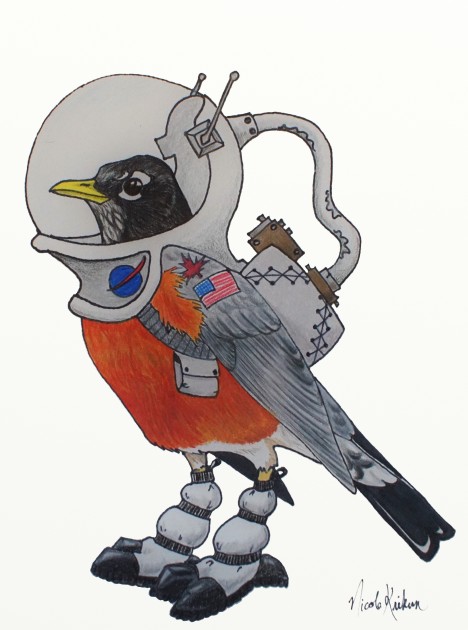

Check out our team T-shirts! Nicole drew this ‘space robin’ and we all liked him so much that we got some fun t-shirts made with him on it. If you looked through the set of slides I posted on the first blog post, you might be able to guess why Nicole drew the robin wearing a NASA astronaut’s space suit. Any guesses?

Ruthie modeling our Space Robin t-shirts.

If you haven’t already figured it out, the robin is wearing a space suit because we are using information collected from satellites in outer space that are looking down at the Earth with special sets of ‘eyes‘ that we call sensors. From these satellite sensors, we will learn about two main things:

First, some of the satellites – the GPS satellites – tell us exactly where the robins are as they are migrating. We’ll call these the ‘bird location satellites’. You can learn more about them here.

Second, other satellites tell us about the habitats the robins are using or avoiding as they migrate – like, if there is still snow on the ground, or if they are spending time in a forest or a grassland, if the plants around them are very dry or sitting in big puddles of water, or if there is a forest fire burning. We’ll call these the ‘bird habitat satellites’. You can learn more about them here.

In addition, a third set of satellites will actually be used to transfer the information on where the birds are, from the bird, to me and my team once we’re back in New York. We’ll call these the ‘information transfer satellites’. You can learn more about them here.

Who knew that robins and satellites could work so well together?!

How to catch a robin

The first thing we did after getting a good night’s sleep was to make a plan for how to catch 30 American robins. I’d assumed that we’d be using the ‘playback technique’ where you play recordings of singing robins on one side of a mist net in the hopes that a curious bird hanging out on the other side of the net will fly into as she or he flies over to check out whose singing in their territory. I was familiar with this technique from my work on another project in Alaska, but Nicole had another idea that she thinks will work better to catch the robins migrating through our field site.

Bird bath with drip to attract migrating robins who are typically thirsty and looking for a place to bathe.

Nicole told us that the birds will be attracted to a bird bath because migrating robins are both thirsty and like to keep clean by bathing, but there’s not a lot of water available to the birds at this time of year because the nearby lake is still frozen and it hasn’t rained enough to create many puddles. So we filled up a big plastic box with water (this is the bird bath), and put it in a nearby field. Then, we got an empty soda bottle, cut a little tiny hole in the bottom, and stuffed a small piece of blue sponge in it. Next we filled up the soda bottle with water and hung it upside down over the bath, so that drops of water would fall from the sponge – kind of like a shower. When the drops of water from the bottle hit the bath water, they make a ‘drip drip drip’ sound that Nicole thinks will attract thirsty robins! We also put up four mist nets in a box shape around the bird bath so that any potential bathers would fly into a net on their way to/from the bath. Genius! Here is a photo of the bird bath and net setup.

While we waited for robins to notice the bird bath and hopefully get stuck in our nets, we went inside to get ready for the first bird that we hoped to catch. Ruthie and I worked on testing the mini-GPS tags (made by Lotek wireless), making sure they were fully charged, and programming them to work once they’re attached to a bird. Brian and Nicole worked on making the harnesses that the mini-GPS tags will be attached to, and my Dad went on a hunt for more harness material.

Not much time went by before our first American robin flew into a net, although it wasn’t one of the bird bath nets, it was a net that the LSLBO’s Bander in Charge (Richard Krikun) had set up about 2 km away for his own study. Thanks for sharing Richard!

Meet our first space robin: Trail Blazer

Meet ‘Trail Blazer’ – our first volunteer space robin! Isn’t he cute?

Ruthie showing her excitement over catching our first space robin, who we named Trail Blazer. Photo credit: Natalie Boelman.

Here is a video and a picture that show how Trail Blazer was caught, how he was weighed, and then equipped with a harness and mini-GPS tag.

Nicole and Brian are suiting up Trail Blazer with a mini-GPS unit and harness. Photo credit: Natalie Boelman.

Once we were sure the harness and tag were secure and not bothering him, we took Trail Blazer outside and released him. He seemed to fly just fine with his new gear on, and perched for a while in a tree to do some feather rearranging. We hung out near him for about an hour to make sure that he was okay. Eventually he flew off confidently, presumably continuing his migration northwards.

Trail Blazer perching on a branch, showing off his GPS unit and harness. Shortly after this photo was taken, he flew off, presumably continuing his migration northwards. Photo credit: Brian Weeks.

Another view of Trail Blazer. You can barely tell he is wearing his harness and mini-GPS unit. The little white band on his right ankle has a number on it that will help bird biologists recognize him in the future. Photo credit: Brian Weeks.

Safe travels Trail Blazer!

Where is Trail Blazer migrating to and where will he start his family?

We won’t know the answer to these questions for another two months from now because the mini-GPS tag that Trail Blazer is wearing will only send information on where he’s been to the ‘information transfer satellites’ once, in mid-June. Not only did we program his mini-GPS tag to collect information on where he decides to start his family, but also to collect information on the migration route he’ll take to get there! We programmed Trail Blazer’s tag to record his location every two days from the day we caught him (today) until about June 15 when his mini-GPS tag will likely run out of battery power. It’s a long time to be patient and wait to find out where he goes. While we’re waiting, we’ve got 29 more American robins to catch and outfit with tags, so we’ll have plenty to do to keep us distracted for a little while.

Check back here in a few days for more pictures, videos and space robin introductions!

Space robin by Nicole Krikun.

This field blog is written for a very special group of people – elementary school children who are curious and eager to learn about Earth and the animals we humans share it with! While I’m getting ready to head to the field, I wanted to give kids like you some background information that should help you understand the upcoming series of blog posts I’ll send from northern Alberta, Canada. I asked my colleague Mary McLean-Hely, who is a friend and expert curriculum developer, to write the article below for elementary school kids just like you – I hope the information is both interesting, and even a little fun! –Natalie Boelman, ABoVE researcher with Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and Columbia University

A space robin mascot for our Migration Mystery. Drawing by Nicole Krikun.

Traffic Jam

Have you ever left on a trip during a school break only to get stuck on the highway with what seems like millions of other people? Well imagine hitting the road with three billion people! That’s about half of the people on Earth!

That’s also how many birds travel, or migrate, each spring from all over North American to the arctic and boreal regions in Canada and Alaska. Some populations of American Robins are among these three billion birds.

Bug Buffet

Why do the American Robins travel north in the spring? The tundra and boreal (or northern) forests near the poles are cooler and provide great conditions for robins to mate and raise families. It’s like an all-you-can-eat buffet of plant life and insects! There are countless mosquitoes that fill the air in big, gray, buzzing, bug clouds. Robins feast on them! They also like spiders, beetles, seeds and berries, which are plentiful. Yum!

In addition, the summer days are very long and provide the busy birds time to find a mate, make a nest, and take care of their eggs and baby robins. There are not a lot of predators, or animals who feed on robins, providing a safe place to raise their chicks.

Although the individual days are long, the breeding season is short. During the short time, birds have to feed their chicks as much as they can with protein-rich insects and spiders. They also have to fatten themselves up as they will need the energy to fly south.

The start of cold winter temperatures tells the birds to start their fall migration. The birds and their young hit the road again flying south to warmer regions, like New York or California, for the winter. It’s kind of like millions of people heading home at the end of summer vacation. We’ll be learning and telling you more about their birdie vacation as it happens, so stay tuned.

Robins migrate between northern and southern regions of North America

Climate Change and a Migration Mystery

Recently, the climate in the polar regions has changed. Scientists think it may affect the migration pattern and habits of the American Robin but they aren’t sure how. It’s a migration mystery!

There are many scientists all over the world studying the changes in the climate in the polar regions. With the information they gather, they learn about how climate change affects plants and animals living near the polar regions.

Together with other scientists, I’m studying the environment, growth of plant and bug life, and other animals in the bird’s habitat. With this information, we will learn how the changing climate affects the birds and other animals, as well as plant life. We’ll be able to make predictions about what may happen in the future for the migrating birds.

Dr. Natalie Boelman

Come Fly with Me!

My team and I are currently en route to visit the boreal forest near the Town of Slave Lake in Alberta, Canada, and they will be taking a new piece of technology. We have tiny Global Positioning System (GPS) devices that we will put on the birds. The GPS device is a radio system that uses signals from satellites to tell you where you are and to give you directions to other places. It works like the navigation in your car or on the maps on a smart phone. It sends a signal about where the bird is the same way a phone sends a signal about where you are. Then, it shows where the bird is on a bird map app.

But how do you catch a little robin without hurting it? Sing it a song! We will attract the birds by playing bird songs. When the birds come, we will catch them in large, soft nets. Next, we will carefully and gently place the GPS devices on the birds. Finally, we’ll set the birds free. The robins will probably be a little scared but they’ll quickly recover and continue on their way. If all goes well, the GPS devices will send data about where the birds are. Our team will use this data to see the routes the birds take as they continue their migration. In this way, these tiny birds will help scientists like us understand big changes facing the world.

An American Robin – without a GPS backpack (Credit: USFWS)

Over the next ten days, I will bring you along on this adventure to Alberta so you can see how we’ll be working to solve the Migration Mystery of the American Robin! I hope you’ll check in every couple of days to see what we’re up to. I’ll do my best to post pictures and short videos so you can see things in action, and meet the members of my field team and the birds we catch. In fact, a group of smart and curious 4th and 5th graders at Cottage Lane Elementary in Blauvelt, New York (where my daughter goes to school) has chosen some great names for the birds, so I’ll introduce you to each of them as we catch and attach GPS tags to them.

To get yourself in good shape for understanding my series of blog posts from Alberta, I suggest you spend a few minutes going through this set of slides I’ve prepared for you! I hope you will find them fun and interesting: http://above.nasa.gov/Documents/blog/CLE_migrationmystery_Boelman.pptx

If you want to learn more about American Robins, I also suggest checking out these websites: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/American_Robin/id and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D3ELutmnT8k. Also, if you feel like some musical entertainment, here’s one of my favorite Raffi songs about robins: https://youtu.be/3R4_g-50CbQ.

While you’re looking through all this stuff, I’ll go pack my bag so I’m ready to get in the car and head to Slave Lake, Alberta. See you back here in a couple of days!