Karibu! Welcome! I just returned from a training in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, after an incredible week focused on using satellite data to better understand complex watershed dynamics and manage water resources. Referred to as Dar by locals, Tanzania’s largest city sits on the tropical east coast of Africa and is full of salty sea smells and friendly people. Our SERVIR colleagues from the Regional Centre for Mapping of Resources for Development (RCMRD) and I spent a full 5 days with Tanzanian water resources managers from the Rufiji Basin, Wami-Ruvu Basin, and other offices focused on…you guessed it…water.

Flowing from the Eastern Arc Mountains, the Rufiji river basin is one of the largest in East Africa and where most of Tanzania’s agriculture grows. The Wami-Ruvu basin is where Tanzania’s largest urban centers (including Dar) and industrial complexes are concentrated, but you will also find agricultural fields. Both basins are vulnerable to environmental factors that affect water quantity and quality. Examples include increased water demand from population growth, pollution from industrial and agricultural runoff, and uncertainty in rainfall patterns as our climate changes. With NASA’s freely-available satellite data, hydrologists can measure streamflow at a given place and time, and estimate discharge using different hydrologic models.

These predictions support sustainable water management, as other factors change in and around the basin. In Tanzania, the long rains are from March to June while the short rains are from October to December. As our climate changes, Tanzania experiences high and low extremes with intense drought or floods with the changing of seasons. These anomalies threaten agricultural production and livelihoods in the region as populations grow, pollution increases, and natural disasters are more devastating. Monitoring and modeling water resources can help to plan ahead and respond more efficiently.

One of the goals of the SERVIR program is to build capacity to use satellite data in the regions we work in by training the trainers with tools, products, and services that aid in environmental management. For this training, we used a common hydrological model– the Variable Infiltration Capacity (VIC) model– to estimate streamflow. Over five days, the intensive training covered the entire modeling process for VIC– from data access and preparation to model run, calibration, and interpretation.

As a result of this workshop, stakeholders are equipped to return to their offices and replicate the process for different sub-basins. Estimating discharge over time with satellite data will save resources and allow hydrologists in the region to better understand long-term basin characteristics for improved management practices.

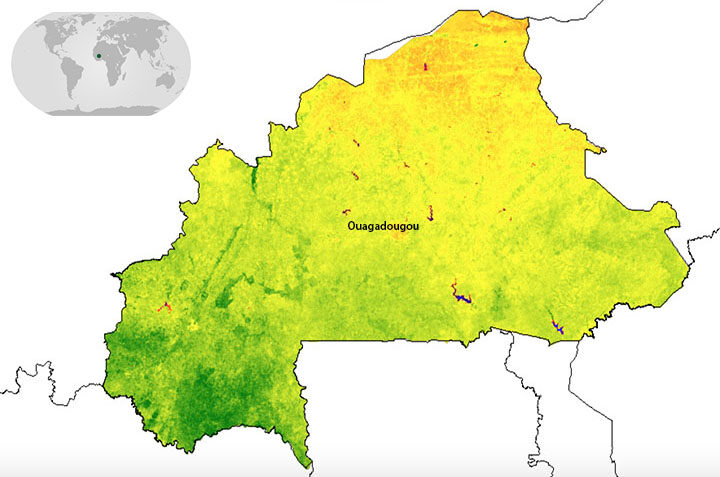

When I said I was going to Ouagadougou (Wa-ga-du-gu), the first question was “where, again?” So let’s start with the basics. Ouagadougou is the capital of Burkina Faso–a land-locked country in West Africa–located to the south of Mali, southwest of Niger, and north of Ghana and Togo. It is home to over 80 ethnic groups as well as Africa’s largest craft market. Burkina Faso also happens to be one of four pilot countries of the SERVIR-West Africa program, which launched in July 2016. The country’s forests are quickly degrading and shrinking; therefore, the first SERVIR service in Burkina Faso focuses on resource management, land use, and restoration.

The week-long workshop brought together members from communes, or sub-provinces, across Burkina Faso with representatives from SERVIR-West Africa, the West Africa Biodiversity and Climate Change (WABiCC) program, NASA, and the US Agency for International Development (USAID). Together, we discussed environmental problems impacting the local communities–from degraded forests due to agricultural expansion, to the build-up of garbage around communities. Through the work of SERVIR-West Africa, one idea is to use satellite datasets (e.g. from Landsat) for land use planning and monitoring environmental degradation.

One major limitation many communes throughout Burkina Faso encounter with any activity is safety. The primary concern of safety is related to terrorism, which spiked in December of 2018. This can be a major hurdle when trying to map the landscape like we want to do with this service, because there is no easy way for someone to physically go to different areas to validate land cover and land use maps. Therefore, one innovative approach SERVIR-West Africa and the Higher Institute for Space Studies and Telecommunications (ISESTEL) is using small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (sUAVs) with cameras attached. I had the opportunity to actually see this technology in action, and the sUAVs drew quite the crowd. The goal is to use this drone imagery to validate the larger-scale NASA satellite data to map communes and monitor changes over time.

The second week of the trip to Burkina Faso included stakeholders from across Niger and Burkina Faso brought together to discuss a wide range of water-related issues. We focused on flooding, groundwater, and surface water monitoring. Each of the partners in attendance were able to discuss what they are currently involved in around these various topics and where they may be able to work together.

After two productive weeks in Ouagadougou, it was time for the sun to set on the trip and for me to head back to the United States. From what I saw of Burkina Faso, it is a beautiful country with plenty of greenery and different flora, delicious food, and lots to see. I look forward to being a part of the innovative work being done with our institutional partners–from the fusion of sUAVs with satellite data to finding new ways to do field work.