By Michelle Koutnik

Each of our six different camping sites consisted of one cook tent, four sleeping tents, and a bathroom area (more on that later). The cook tent was a “Scott” tent, which is an enduring style and named for the polar explorer Robert Scott. It was a tight space for five people but we were able to crawl in and then sit around together with one person managing the two-burner propane stove in the corner. The Scott style tent was much sturdier than our mountain-style sleeping tents, but it was also more time consuming to put up and heavier to transport. Since we were moving nearly every other day, we wanted to keep our camp as simple and as light as possible. The Scott tent was a necessary addition for cooking, but also as a reliable shelter in the two strong storms we experienced during the traverse.

It took a few hours to set up camp, and a similar amount of time to break it down and repack the gear on the sleds. Randy, Jessica, and I were responsible for breaking down most of the camp and for setting up some of the camp on our own while Clement and Ludo collected radar data on traverse days. Once camp was set up at a new site, we could start melting snow for water and start cooking dinner.

On a traverse day, our camp life included the take down and setup of camp, plus collecting radar data. On an ice-coring day, our camp life included digging and sampling the snow pit, drilling the ice core, and eating a hot lunch. We ate well out there! Our standard meal plan included tortellini with pesto, spaghetti with meatballs, sausage with rice and vegetables, and burritos. Sausages were popular and made their way into many meals. Special nights featured hamburgers with tater tots, and on Christmas we cooked scallops with rice and vegetables. Hot lunch on ice-coring days featured cheesy bagels fried with butter in our cast-iron pan. Since all the cheese and bread was always frozen, it required frying it all together before we could eat it – but it tasted great this way! Stormy-day food was simplified but did afford us the time to enjoy pancakes (two storms, two pancake breakfasts).

The storms also affected our standard bathroom situation – usually a snow pit and tarp configuration. Ludo took the high winds and blowing snow as a challenge and created a snow-brick bathroom, which we tried our hardest to maintain from drifts!

Maintaining camp and completing the science goals was a big job but we enjoyed being out on the ice sheet. For example, Christmas was a wonderful day to share together because a big storm started to clear, and we had lovely gifts to exchange, two small Christmas trees, and a very nice meal. Overall, the camp life was comfortable and enjoyable and with such a hard-working team, we were efficient at all the tasks necessary to make the camp run and be successful with the science.

By Clement Miege

Hi there! After more than three weeks spent in the field, our team is very happy to be finally back, with many memories of the traverse. This year has been a very intense experience and I would like to tell you a little more about this expedition. I will focus on the days we were doing radar surveys. Indeed, two different studies were set up during this field work. The first one was during the traverse days, where we did a radar survey from one camp to another with a range of 50-90 kilometers (31-56 miles) between the camps. On the other days the surveys were smaller, set up around each camp; they consisted of a 10-km bowtie and a 280- by 280-meter (918- by 918-ft) grid to get a better idea of the spatial variability of snow layer depth surrounding each core site. These grid surveys will show us how representative the ice core is compared to the surrounding area and help answer the question of whether we would have gotten a different result if we had drilled our ice core a few paces this way or a few paces that way. We were also looking more in detail at the layering in a 2-meter (6.56-ft) snow pit; to do that, we were using a metal plate at different depths of the snow pit.

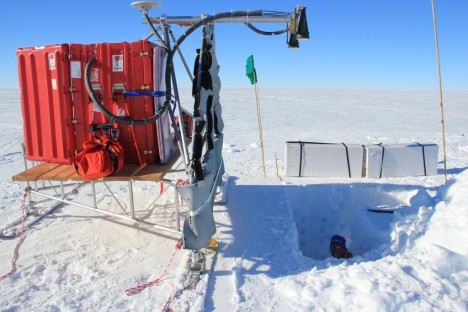

Here is a picture showing the two radars that operated simultaneously on the sled:

Both radars looked at the first 20 meters of the snow pack, sending electromagnetic waves into the snow. The snow radar (the big green horns in the picture) operates in a frequency range of 2-8 GHz. The other radar (the smaller brown horns) is the ku-band radar, sweeping between 12 to 18 GHz. The lower the frequency, the deeper the radars look. We have both radars for some redundancy in the system, imaging the snow/firn closest to the surface, which we core twice, and then the snow radar peers deeper than the cores to provide literally a deeper look. In addition to the 2 radars, we needed to know the elevation we were at, which is important for comparison with airborne data and also for modeling precipitation and temperatures. For that, we simultaneously collected GPS coordinates, which gave us our exact latitude, longitude and elevation every 5 seconds. The GPS antenna was on the very top of the sled, about 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) high.

On this sled, beside the radars sitting in the red box, we had packed: a blue bag, two black duffel bags and an orange bag. The blue bag was a survival bag, with all the gear needed in case we would have been caught in a storm; it included a tent, a stove, a shovel, and some food. The two black bags contained Ludo’s and my sleep kits, and the orange bag had some extra food, in case we were stuck for couple days. For the snow mobile, we had a repair kit under the seat to troubleshoot a possible failure. We were carrying two extra cans of gas as well. With this set-up, we were able to get a pretty light sled that was still comfortable and had all the gear we’d need in case of a storm or other circumstance separated us from the rest of the team, who were carrying all the camp gear. Fortunately, this never happened!

But now, let’s go back to the survey. The travelling days were the ones where the team was the most vulnerable: while we were traveling we had no shelters or camp set up to get back to if anything went wrong because we had to break down the entire camp in the morning, pack all gear on the sleds and ride with the snowmobiles pulling the sleds to the next camp. After driving between 50-90 km (31-56 mi), we would build our new camp, usually that same day in the afternoon. We had a total of seven travel days, covering a distance of about 500 km (310 mi).

During travel days, the radar team left camp first, mostly because we had to drive at low speed to ensure the radar’s safety. Indeed, on the days we ran into large sastrugi (small ridges of hard snow), we drove at less than 10 km/h (6.2 mph). These sastrugi made our travel a little bit more difficult. Toward the end of the day, the team responsible for breaking down camp would leave the radar team and go 20 km (12 mi) ahead, to start setting up the new camp.

The days we were at camp, we did some small radar surveys: a bowtie and a grid around the core site. To help us drive the snowmobile straight for the grids, we set up flags to visualize the corners and sides. In the deep field, everything is white and flat, so it is hard to maintain a nice bearing just by following the GPS for such a small grid.

The last side survey with the radar was done in the snow pit. After analyzing the snow pit and picking up snow samples for further laboratory analysis, we used the pit to calibrate the radars and look at a detailed snow layering for the top 2 meters.

To conclude, I want to say that this traverse was definitely an amazing experience and I was happy to share such a good time with the team. I am already excited to start looking at the radar data in detail to see what we can learn of the past few decades of snow accumulation in this part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

By Michelle Koutnik

Now for a recap of our adventure! We arrived in Christchurch on November 19 and returned there on January 5. We spent 17 days in McMurdo before leaving to Byrd camp on December 7. It took only a few days to prepare for the traverse and we left Byrd camp on December 10.

The traverse lasted 18 days, with the longest time spent at camps 4 and 5 due to the storm delays. Otherwise, we moved fast! We spent an extra day at camp 3 to drill a second ice core, but by the end of the trip we were such fast drillers that we were able to drill two cores in one day at camp 6. We drilled ice cores at nine different sites (including Byrd Station), dug and sampled 6 snow pits, and collected more than 500 km (310 mi) of radar data.

Back at Byrd, we broke down our gear and with the help of the Byrd cargo handler we had it all packed on palettes in one day. Ludo and Jessica went by Twin Otter to pick up the ice cores on the day after we returned to Byrd so that soon after the traverse ended we were finished with almost all our work! In 18 days we finished all of our science, but to achieve these goals it took near seven weeks of travel and preparation – it is not easy to do work in Antarctica!

After the traverse was finished, we could not get a flight out of Byrd Camp back to McMurdo station for a few days so we enjoyed our time with the Byrd Camp crew and rang in the new year with a gorgeous dinner and dancing with the whole camp. Then we had a fast two-day turnaround from McMurdo to Christchurch. We all worked to clean and return all the gear we used in the field and ship all of the science equipment back to the U.S. It was very satisfying to complete all of our goals and finish on time despite weather and flight delays during the season. Great work, team!!

By Bob Bindschadler

Christchurch (New Zealand), 18 January — This will be my last entry in this season’s blog. I had hoped to tell a different tale the past two months —one of successful science being done in a harsh, remote place by hardy individuals dedicated to getting information that had direct relevance to your lives and the lives of others you know and will never know. But the field season unfolded in a vastly different way. I have prepared an outbrief for the National Science Foundation that speaks to the good and the bad, what went right and what went wrong, and how to use what was learned this season to improve our chances for success next season. That document is the official record and won’t be shared here, yet it contains no surprises from what you have read.

For this blog, I want to be more reflective and to emphasize those more personal aspects of Antarctic field work. It takes a lot of people working together to undertake a project as ambitious and as challenging as this one. This season, a lot of us involved in various aspects of this enterprise came together and grew to know each other a lot better. We did not always see things the same way, but I think just about everyone came away with a greater appreciation for what the project is all about and what talents each player has contributed to the greater enterprise. This was most apparent at PIG Main Camp where the great distance from McMurdo provided a clarity of purpose that often gets muddled in McMurdo. Following our limited success in the final days, I was impressed with how the Main Camp staff shared their congratulations with us. That success made their efforts at camp worthwhile. Our assistance in many of their camp chores showed them that we appreciated their efforts. That is the magic of a deep field camp. Even the Twin Otter pilots, who only dropped in for two days, felt good because we accomplished some objectives together.

I regret that the helicopters never came. I have little doubt the same camp magic would have occurred there, too. I question whether managers of the individual U.S. Antarctic Program components, who spend no time in the deep field, really understand how the deep field camps actually operate. There is a bonding motivated by the Antarctic environment that is much stronger in the deep field than in the more “civilized” McMurdo. Even large, multi-project camps can sometimes be absent of this mystic, but PIG is not of that ilk. You do not resent the person who has helped you set your tent, who you have helped shovel out a fuel bladder, who has watched you to make sure your nose is not frostbitten, and whose sled you have helped pull. The shared experiences bring people together and make for one. Every one of the camp staff expressed their hope to be chosen to come back next season.

As will we. We will succeed. Despite the limited scientific accomplishments this season, we are better positioned (with all the camp material, most of the scientific equipment and scads of fuel already at PIG Main Camp to spend the frigid winter) and logistically wiser to design a better field effort for 2012-13. We have to—it will be our last chance for this project. We’ll use satellite imagery to give us an early look next October. In November, Twin Otters will be used to assess the surface character of the ice shelf and to deliver a skeleton crew allowing us access to the wintered cargo, the fuel and to start on-site weather observations. By December, before the main camp even gets set up, the drilling team will arrive and will be transferred to the ice shelf with the drilling equipment by those same Twin Otters. Building the Main Camp and transferring the helos out will come later, much later if need be. Fewer Herc flights, earlier traverses and more Twin Otter time is a much more palatable recipe.

It saddens me to think that even today we should be working out of PIG Main Camp, making day trips to collect radar and seismic information on the shape of the ocean cavity beneath the ice shelf. Instead, our field team has disbanded. We flew to Christchurch together on Monday, but now we are scattering across the globe on various commercial airline flights. I’ve received word that the second traverse has arrived at PIG and this week there should be the final two flights pulling out the camp staff after they have put all the wintering cargo up on high snow berms. A recent satellite image taken last week shows the camp and the AWS webcam is still keeping watch from the ground. It looks like another beautiful day there.

I’m not exactly sure how to end this blog. I hoped you’ve enjoyed the story. I suppose I could just say that we now reenter the planning phase. There is yet more pressure on us now because we have one more shot to get it right. I think we will, but as always, the big unknown is what Antarctica has in store for us next time.

By Bob Bindschadler

McMurdo (Antarctica), 14 January — Delayed flights seem to be the rule this season. Our flight to Christchurch was cancelled late Thursday night because of expected bad weather here. On the next try, there was a mechanical problem that required a part that had to be shipped to Christchurch, so I’m still in McMurdo. The next attempt by the C-17 will be to fly to Antarctica on late Sunday. If successful, we will board it in the early morning hours of Monday and we’ll be smelling the lush summer greenness of New Zealand five hours later.

Let me return to the saga at PIG Main Camp. I left the tale at the point that I was being told on Friday, 6 January, that if the helicopters had not been flown to PIG by the end of the following day, they would not be delivered this season and my field team would be returned to McMurdo—game over, season ended. I objected—not to the date, nor to the conclusion that there would not be enough time to execute the drilling/ocean profiling part of the field work. What I objected to was calling a halt to other science activities that still could be supported with the helicopters. I pointed out that our second science objective did not require a separate camp on the ice shelf, but could be supported by day trips based entirely from the PIG Main Camp. In this case, four days would not be spent transferring people and equipment to the ice shelf camp, and another four days returning them. These could be spent gathering data from isolated places on the ice shelf only accessible by helo and everyone would be back in Main Camp every night. There were many days still left where important science could (and should) be done. Better yet, by not having a remote camp that could only be pulled off the ice shelf by the helos, the helo schedule for disassembly for return to McMurdo was no longer at risk. But the helos still had to be flown out to PIG to do this work.

“No” was the answer. I was stunned. Something very fundamental had failed to be understood while I was in McMurdo; our science program had many components and when I had presented our prioritization of the individual elements and focused on achieving the most important element (the drilling and ocean measurements), it did not mean that it was “drilling or nothing”. Once the drilling objective could not possibly be met, the next step was to consider how to achieve the next most important objective. Not only could this second priority objective be met (there were still nearly two weeks we could have worked on it), but the risks to the helicopter schedule were much lower. The logic was ironclad, yet no one in McMurdo supported my appeal to still fly out the helos.

“No” remained the answer, and when it came from the National Science Foundation’s on-site head of logistics, there was no point in continuing to stress either the science to be gained or the reduced risk to the helo schedule. Most scientists will bristle when sound logic fails to persuade and so it was with me. This made no sense to me and I was not receiving any suitable explanation over the sat phone. Enthusiasm for this project on the part of the helo operators had noticeably decreased as the schedule delays mounted, but supporting this new science objective reduced their risk. However, I feel they now had what they wanted—a deadline that had passed that reduced their risk to zero and they would not let that go. Science wasn’t going to get done. That was my problem, not theirs. Nor did NSF seem to care enough to order the helos to PIG. ^%$^%#&*!!

I was done, right? Not quite. I’m nothing if not dogged in my determination to get something to show for the extraordinary effort that had led to us being where we were. At the very bottom of our science priority list was the task of setting out five GPS receivers and seismometers on the ice shelf to monitor the flexing and cracking of the ice shelf that we think is driven by the spatial variability of the strong melting of the ice shelf’s underside. Because the Twin Otter had landed already in the area where these instruments could be useful, I pleaded for enough Twin Otter time to put out a minimal set of three of these instruments. I expected three days would be required (they had been willing to provide two days to help set up the drill camp, so I had some hope this would be feasible in their minds). There was silence on the phone, but shortly McMurdo voiced some willingness to consider this request. They would have to see if the impact of this new request could be accommodated, but they were optimistic. Whew, not much, but something!

The next day I was told that we could expect three days of Twin Otter support to put in three GPS/seismic stations; not just any three days, but Monday through Wednesday, but that I should try to accomplish it in two. And it would start…tomorrow. The very next day?! I had to accept. We had to hustle to pull out of our cargo the required pieces (as the lowest priority activity, these pieces were scattered around and well buried in other gear) and pre-fab as much of the instrumentation as possible before the Twin Otter arrived. We worked late into the night and went to bed hoping that the weather improved enough that the Otter would come the next morning.

Morning clouds parted quickly the next day and we heard to expect the Otter to arrive by 10:30 AM. We were (just) ready and had a quick conversation with the pilots about what we wanted to do to set out five (not three) stations. We loaded 1,500 pounds (680 kilograms) of gear and within 10 minutes three of us were off, bound for the ice shelf. The day was absolutely brilliant. Winds were calm and the temperature above freezing. I recalled the day almost exactly three years earlier when I had last been on the ice shelf and experienced similar weather. It took us a few hours to complete the first installation. While we were working, the Otter returned to the Main Camp and returned with Mike Shortt, our team member from the British Antarctic Survey, who had joined our group to make special radar measurements that, when repeated at precisely the same spots next year, will be able to determine the local rate of basal melt. We were done by mid-afternoon, so we returned to Main Camp, picked up a similar pile of gear for the second installation and were successful in getting that established, returning to camp for a late dinner. It was a heady achievement and everyone shared in the joy of it. We had been in Antarctica for five weeks. Finally, we had some science to show for the time.

Our dinner respite was brief. We felt we had a good shot at getting our remaining three stations in the next day, but we had to complete the pre-fabrication on each of them. Oh yes, tomorrow was also going to be the day the Hercules helicopter came. This was the first Herc since we arrived a week earlier. It would not have the much-hoped-for helicopter on it, rather it was coming to deliver camp-take-down material and return six of our field team. The only scientists allowed to remain were the four who were putting in the stations. The others had worked all day reorganizing our cargo into pieces that either stayed for the winter, or returned to McMurdo and home institutions. It was a big job. Everyone worked well into the night. Some stayed up very late despite the bone-chilling wind to ensure that we were ready for both events the following day.

The forecast called for good weather Tuesday, but when the day began, the fog was thick in the direction of the ice shelf. Not good. It was clear that my three days of Otter were counting down. A delay for weather and we would probably lose the Otter. The other science group at Byrd never wanted to see it go and was very anxious to get it back. Fortunately the Otter crew heard some encouraging words from the weather forecast center (in Charleston, SC) and by 10:30 was willing to try to get back to the ice shelf. We loaded the plane quickly and were airborne inside half an hour. The pilot found a way to skirt the fogbank and to our delight (and considerable relief) found our desired sites sparkling in the sun. Stepping out of the Otter, we were greeted again by warm conditions and very little breeze. Perfect!

The third installation went in without a hitch. It was all I was approved to do, but we had the other two ready and I was not about to stop. We rushed back to Main Camp picked up the fourth kit and had it in place and collecting data three hours later. Because of the late start, the Otter crew was beginning to look at their watches to make sure they did not exceed their allowable hours. Travis, the pilot, told me that if we could install the final site in two hours, he would get us there, but when he said it was time to return, we had to stop right away. Confident of our increasing efficiency, I was game but I got a little concerned when we returned to Main Camp to pick up the final setup and discovered a big smelly Herc sitting in the fueling area. That was the one spot on the entire Antarctic continent where we had to be right then and it was taken! This was the Herc that I had so desperately wanted to bring a helicopter. Instead it sat there in my way, loaded with the remainder of our crew, taking them back to McMurdo without ever being given the chance to do the work they came to do. Out of the way!

The minutes of delay seemed like hours, but the Herc evenutally vacated the spot. We loaded and refueled so quickly we almost beat the Herc into the air. The four of us were all primed to get this final installation done in record time and with the help of the Otter crew, we succeeded with time to spare. That was it; our season was over. Five weeks of plodding, waiting, anticipating, concluded by two hectic days of installing secondary equipment on the ice shelf. Nevertheless, something was far, far, far better than nothing at all. We were exhausted, the camp staff shared our joy once we returned, but again we had to forego a long night of sleep to ensure that we put all the tools and gear we had used the past two days in the right places and that what was to happen to every piece of our equipment was clearly understood by those staying behind to close down the camp. Each piece of winter-over material would have to be carefully arranged on a tall snow berm to (hopefully) survive the long, harsh winter.

The next morning was our last at PIG Main Camp. Another Herc (the next to last for the season) would not come for seven days, so we were permitted to fly with the Twin Otter as it returned to Byrd Station. Much to our amazement, when we arrived there, we were told that a Herc was due in an hour. All we had to do was wait in the galley sipping tea and sampling their excellent baked goods. Three hours after boarding, we were back in McMurdo.