May 25, 2024

Some 25 of us were up before 6 a.m. to head out on the bus from the hotel to Burlington International Airport to catch the C-130 aircraft, a military transport plane repurposed for NASA fieldwork, to begin our 7-hour flight to Pituffik.

Several mountains of baggage, including scientific instruments and personal luggage, separate us from the less-well-heated economy cabin, which was probably reserved for graduate students, though we are far too collegial a group to check seat assignments. As we head north and east, the landscape out the window is vast, entirely gray-scale, and unforgiving: sea ice with streaks and patches of open water as far as one can see in every direction.

About halfway through the flight, we cross the Arctic Circle. Here the scene is often reduced to pure gray, and one cannot tell what is sea ice, snow, or cloud. This is the challenge we have long faced when attempting to interpret our remote sensing imagery; now, as an early gift of the expedition, I experience it directly.

May 26, 2024

The site is halfway between Washington and Moscow. Most or all of the buildings were prefabricated, brought here by ship in the summer, and mounted on stilts due to the permafrost. Some rough grasses are the only apparent vegetation.

In some ways, the base is well appointed. There is a sports center with an abundance of every conceivable exercise machine, also a tanning machine and a perpetual pool, a huge gym, and a yoga room. There is a recreation center with a movie theater, a lounge area with free apples, tea, and coffee, a game room that is more like an arcade with multiple video machines, and a craft center that has sewing machines (including a state-of-the-art Serger), rock cutting and polishing machines, computer graphics, and printers.

This is a remote place. The site is protected by a thousand kilometers of ice in nearly all directions, and the only ways to get here are by air or by boat for a couple of months of the year, when the sea is not frozen. With full daylight all day and “night,” the times-of-day are marked only by artificial clocks; the natural ones are essentially absent.

May 27, 2024

This was mostly a flight-planning day, getting ready for the first science flight of the campaign. It turned cold, windy, and snow fell today. This was more like what I expected but didn’t experience during the first two days. But now it is sunny again, around 6 p.m., and near-freezing, so there is still standing water on the roadways, and we are past the season when it is safe to walk on the ice-bound bay. The severe environment calls for some specific adaptations.

For example, the outer doors have latches that seal upward, so a bear pushing down on the handle will be unable to open the door. The walkways are made of open steel grids, so snow and mud will drip through. Boots are to be brushed before entering buildings, and plastic boot covers are provided in an effort to limit the amount of dirt that is tracked in.

I took a late-night walk. It’s daylight anyway, though overcast, windy, cold, and flurrying. Pretty much what I expected here.

The power went out twice today. Everything goes down, including the internet. I’m trying to keep everything charged, in case it happens again. Today’s weather represents “Condition Alpha” for storm warnings. That means just be on alert, in case things change. Condition Bravo means you cannot go outdoors without a buddy, or drive alone without a radio. Condition Charlie means you can’t walk out at all; there is a base taxi for urgent movement. Condition Delta: shelter in place.

The pipes are all above-ground because of the freeze-thaw cycle that would destroy the pipes. I guess they must be heated and insulated. They cross the road by going overhead.

Car and truck engines must be heated to avoid freezing and cracking. So, many of the buildings have power cords hanging out in front to run electric engine-block heaters. I didn’t take the last picture quite at midnight, but the scene doesn’t change much during the night.

I think I mentioned that it is mud season here. This is no joke. The place has a very industrial feel, and the only place to walk is on the mud roads. I’ve heard it will get worse as the mud deepens, and mosquitoes come out. Something to look forward to…

May 28, 2024

We had our first flight with the P3 today, and it was far better than I had expected. There was a rare case of cloud-free atmosphere over sea ice in one area north of Greenland where some buoys had been deployed, which allowed for both surface ice and aerosol characterization. Also, a nearly 3-hour run at ~500 feet captured aerosol properties over open water along the northern part of Baffin Bay. Among our objectives are learning the sources and properties of aerosols in the Arctic, their evolution as they age, and their impact on clouds. Others are especially interested in the properties of sea ice as it melts. So, this gives us a start on those objectives.

May 29, 2024

The wind is a force of nature. Today it has been blowing at something like 40 miles per hour, with gusts considerably higher. It literally takes your breath away—and this is just Condition Alpha.

Gusts create the sensation of blowing you away. All this under a relatively clear sky, bright sun, just a few clouds. It is somewhat other-worldly to one who has lived a life at lower latitudes. The temperature is only a few degrees below freezing, but the weather today gives new meaning to the term “wind chill.”

June 1, 2024

Today was an official day off, and in particular, a mental health day for the forecasters. Several of the military folks on the base arranged to take a group of us on a hike over the Greenland Ice Cap. There were 15 of us in five trucks. The trip involved a fair amount of driving on gravel roads in trucks—about half the time driving, half hiking – 5 hours total. The hike itself was about 5 or 6 miles, and we walked around and then on the glacier, though we never did find the Starbucks.

In addition to the stark beauty of the rock fields and ice, the sky is unlike anything we normally see at lower latitudes. The surface is cold, and the atmosphere is no colder (and sometimes is even warmer) than the surface, i.e., it is stably stratified—the “warm” air is already up, so there is not a lot of warm air rising and mixing that typically happens when the surface is heated directly by the Sun.

The glaciers have brought an enormous diversity of stones that litter the ground, and every piece of wood here was carried in from somewhere else. There are little clumps of vegetation, just enough to satisfy the appetites of musk oxen.

So far, I’ve seen Arctic fox (no pictures—they disappeared too quickly), musk ox in the distance, Arctic hare, and snow goose. No polar bears—and no complaints about that.

June 7, 2024

This evening I took a long walk out to the ice-bound pier… AND I SAW AN OTTER!!!

June 4, 2024

The Arctic foxes are molting. They were very cute when their coats were all white. Now they are losing their winter coats and turning brown. I did see a couple of full white coats, but was too slow to get a photo.

June 8, 2024

The project rented a van, and ten of us went off to climb the Dundas, that imposing rock feature not far from the base, though to get there without walking on thin ice (here the term is not merely a metaphor), one has to drive about 30 minutes over rocky and sometimes quite steep roads around the frozen bay.

The angle of repose is the angle a pile of dry sand (or salt) will make if you dump a bucket of it on the ground. It is generally steep (depends in part on the grain size and shape of the sand particles). Dundas is about 725 feet high; it appears to be the remnant of a glacial moraine—rock pushed here by an advancing ice sheet at least that high, that remained after the ice melted away. It is loose sand and rock, mostly gravel and cobble-sized. The climb up was, frankly, arduous, as there are not a lot of footholds.

The first part was steep enough that going on all fours was necessary in places, and the sand and small rocks would slip easily down the slope as one persevered upward. The final part was up a sheer rock wall that was graced, mercifully, with a sturdy rope. My pictures are lacking for the entire traverse, as all my effort went into the climb itself. I did stop part way up the rock wall to check my life insurance policy.

The view from the top was spectacular, but truthfully, there are so many great vistas in this rugged place that the main reward was accomplishing the ascent itself.

The way down was similarly fraught, except that below the rock wall, I had pretty much no choice but to slide down bit by bit—the loose surface material would give way at every step. So, on my back, lift up my rear, slide a few feet using my boots to stop, and repeat. There was some interesting vegetation on the slope—tiny plants and lichen, which I did photograph. I’m told that some of these plants can be hundreds of years old.

In the distance, we saw some dark spots that the binoculars suggested were seals. (Oh, yes—someone here said that my otter from last night was actually a ring seal; not sure that is authoritative, but…).

June 9, 2024

I agreed to join this afternoon’s walk up the edge of the Greenland Ice Sheet.

The slope is moderate by Dundas standards, and the path is completely snow-covered. The walk up is of course uphill, and a steady wind of 30–40 mph (the katabatic wind), with significantly higher gusts, blows off the ice. This guaranteed that however far we got up the ice sheet, we would certainly be able to make it down, either on foot or airborne.

There were pools of water within ice basins at the base. They look a beautiful shade of blue. We saw this in Alaska as well. I think it must be that ice either absorbs all the longer wavelengths, or it preferentially scatters blue, or both. The optics here are stunning, at least to me. Probably because they are unfamiliar.

One way painters provide a sense of distance in a painting is with “atmospherics,” that is, they increasingly blur the edges of more distant objects to account for light scattering by atmospheric gas and aerosols. Mountain climbers experience the opposite, in the thinner atmosphere, remote objects are sharper than they would in everyday experience, so more distant objects appear closer than they actually are. This is true here in Greenland as well, though we are not at a very high elevation along the coast. I expect the phenomenon in this case is due to a very clean atmosphere.

June 11, 2024

Today I got to fly on the P-3. Every satellite scientist should be required to take at least one such flight to see what the Earth is really like. We flew across northern Greenland and over sea ice. In the two weeks since the campaign deployment began, the depth of the sea ice, and the snow upon it, both decreased at those buoys (where it was measured), and, of course, most everywhere else as well.

A field campaign is a layered operation. Aircraft flight scientists build, run, and maintain the twenty or so instruments that measure particle composition, gas concentration, cloud properties, surface reflectivity, and upwelling and downwelling energy. They are awake by 4 a.m. to prepare their instruments for flight, worry about power supplies and calibration, then sit on the plane for six or seven hours, noting what they see from their measurements and out the window.

The number of leads (i.e., openings in the ice) has increased in places. We flew at high elevation to survey the area, measure the overall surface topography and reflectance, and sample aerosol layers aloft, then descended to 300 feet above the ice to capture aerosols emanating from the surface. The photos tell an accessible part of the story. The rest must be teased out of the data in the coming months and years. But my ride is over for now—there is an aerosol forecast due tomorrow.

June 12, 2024

It was flurrying this evening, and my walk carried me down toward the pier. But you might be pleased to know, I did not go all the way; several seals have now been seen on the ice at the pier. My otter or seal in the water was the first anyone saw, and although they say it is relatively rare for bears to go near the base, seals are their primary food. I figured, after a long winter hibernation, a bear might not count me as even a light snack, but in consideration that I had already booked my flight home, I turned around before getting very near the water’s edge.

June 14, 2024

I should say that the food here is okay. Better than I expected. Of course, in such circumstances, it pays to begin with low expectations: hardtack, pemmican, and beef jerky. The cafeteria serves a lot of beef and pork, but there is also chicken, a reasonable salad bar, excellent, fresh bread (the highlight in my opinion), always two of THE three kinds of fruit (apples, oranges, and bananas—so yes, they mix apples and oranges), and of course, Danish, at least in the morning.

In the evening I took a walk, as usual, and ended up in one of the dozens of prefab buildings on the base, with the suggestive label “Heritage Hall.” The door was not locked, and the lights turned on as you entered each room. The place is a sort of museum, a repository for things discarded from the 1950s and 60s.

They have a computer punch-card machine, a vacuum-tube TV set, and a radar scope you will recognize from science-fiction movies. Also some notebooks with photos of the army’s Camp Tuto (now abandoned—only remnants of the airfield remain) and the presumptive city “Camp Century” they built into the ice in the 1950s. The walls flowed at glacial speed but ultimately collapsed.

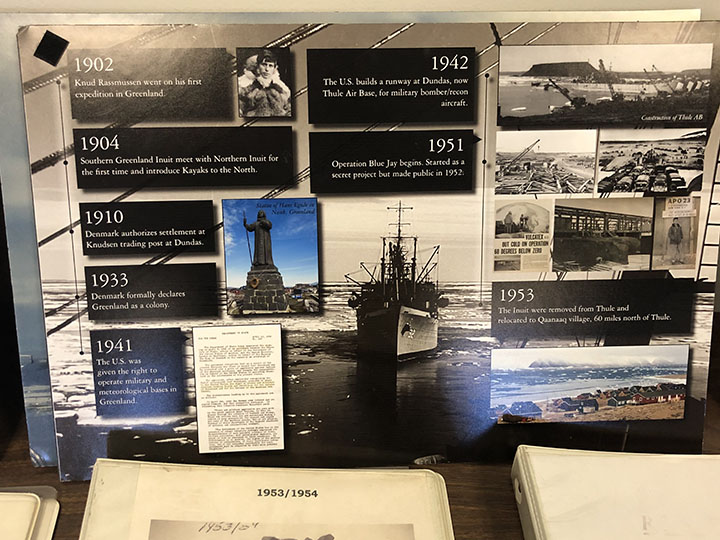

Thule base was established in 1951, succeeding three waves of Inuit who inhabited the area, apparently beginning 4,500 years ago. The most recent came around 900 CE, met the Norse about 100 years later, and were moved to a new village 60 miles to the north in 1953. There is even a Life Magazine cover showing ships delivering material to the base in September 1952.

Ralph Kahn, an emeritus research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center now at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado Boulder, spent three weeks at Pituffik Space Base in northern Greenland in the summer of 2024. He was one of dozens of scientists who participated in ARCSIX (Arctic Radiation-Cloud Aerosol-Surface Interaction Experiment), a NASA-sponsored field campaign that made detailed observations of clouds and atmospheric particles to better understand the processes that affect the seasonal melting of Arctic sea ice. These excerpts from his emails home to family provide a glimpse of what life was like on one of the world’s most northern scientific outposts in the world. Photos were taken by Kahn or Gary Banzinger, a NASA videographer who also participated in the campaign. Kahn, an atmospheric scientist, worked with colleagues to provide daily aerosol forecasts that were used to help plan flights.

Hello from the Goddard Instrument Field Team! Earlier this summer, we visited Katmai National Park as guest researchers. These are some of our photos and notes from the field.

In June 1912, the largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century blanketed glaciers with ash in what’s now known as the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. Our 2024 expedition took us deep into the valley, seeking answers about icy volcanic landscapes on Earth, Mars, and beyond. The data and samples we gathered here will help us understand how these buried glaciers and the volcanic deposits on top are evolving over time.

How do you pack for nine days of hiking and camping in bear territory? Carefully! We secured food and scented items in bear-proof canisters, mapped out tent placements to fit within the perimeter of a portable bear fence, and worked closely with Katmai National Park to minimize our impact while in the backcountry.

The journey from Anchorage to our base camp near Knife Creek included flights on tiny aircraft, “Bear School,” a school bus equipped to ford rivers, and a sixteen-mile hike complete with more water crossings and high winds. On day two in the field, a helicopter carrying large items, such as heavy science gear and a group water filter, reached the valley. In case weather prevented the airdrop, we were ready to complete some key tasks using just what we carried on our backs, but we were glad to see the equipment arrive.

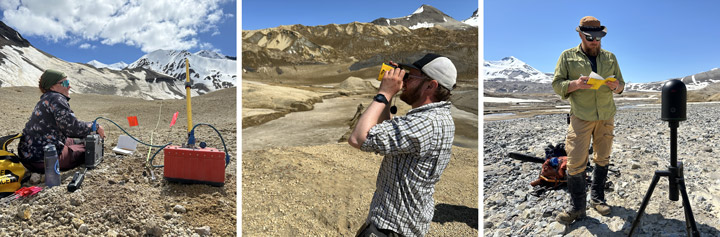

In the field, we worked on and around glaciers covered in huge piles of ashy debris. Some team members used ground penetrating radar (GPR) to scan subsurface structures from above. Together with drill coring, hand-dug pits, and a soil moisture probe, GPR gives us insight into what’s going on underground.

Other scientists studied the insulated glaciers from a different perspective: edge-on. They used laser ranging techniques to find out how the face of an ash-coated ice cliff morphed and receded throughout our week of work. We’ll compare these on-the-ground measurements with orbital images of the same area captured over longer periods of time. Combining field data and satellite imagery helps us better understand how the glaciers are evolving.

We’re a team of planetary scientists, so our science questions on this trip applied to both Earth and other worlds. How does a blanket of ash affect the way glaciers are preserved? What chemical and mineral signatures can we find in the debris from a huge volcano like this one, and how are those signatures changing? What can the patterns we see today tell us about how microbial life has interacted with rock in this extreme environment?

Many planets and moons have volcanic pasts, and we’re still trying to learn exactly what kinds of volcanism have shaped their surfaces. Ice is common throughout our solar system, too. Ground-truth data from field sites like this one can help us interpret evidence found on faraway worlds, where it’s harder to collect and examine samples.

Learn More

Into the Field with NASA: Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes

Comparing Earth and Other Worlds: NASA Planetary Analogs