Mangrove forests are some of the most productive ecosystems in the world, sustaining the livelihoods of millions of coastal dwellers. These unique forests sequester carbon, protect coastlines and infrastructure against storm surges, promote fisheries, and are sources of lumber and charcoal. Last week I supported a workshop at the University of Guyana on using Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) to monitor these unique ecosystems with my colleague Glenn Hyman from SERVIR-Amazonia and Marc Simard from NASA-JPL (Check out Chapter 6 of the SAR Handbook for the training/tutorials).

When I arrived in Georgetown, the capital of Guyana, I was impressed to learn Guyana’s coast is as much as 2 meters below mean high tide! The country already foresees problems of (intensive flooding and saltwater intrusion) in its lowlands related to sea level rise from climate change.

That is why Guyana’s government agencies, NGOs and SERVIR-Amazonia are working to support the generation of an operational monitoring system for mangrove forests. Mangroves can serve as a natural sea wall by building up soils and sediments, protecting the coast.

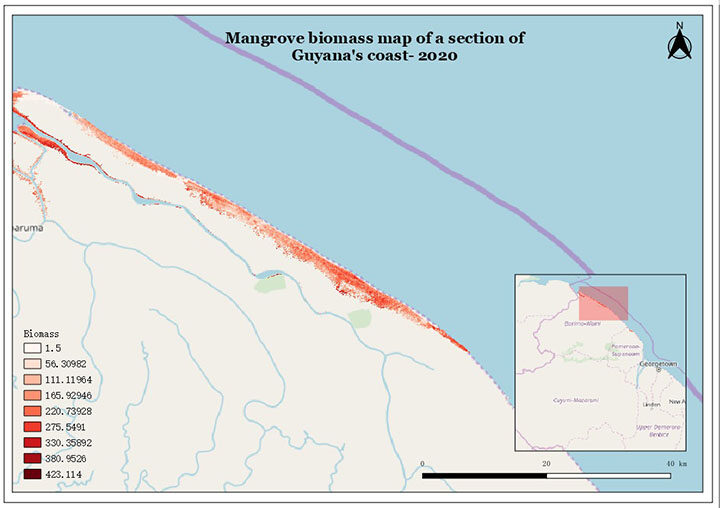

This first workshop exposed participants to available satellite imagery, including the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA) ALOS PALSAR data, ALOS PALSAR 2 mosaics, and the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Sentinel-1 data; as well as how to use the Alaska Satellite Facility’s (ASF) Vertex to access these datasets. Participants also learned how to pre-process radar data using ESA’s SNAP platform, and how open-source QGIS software and digital elevation models (SRTM and TanDEM-X) can be used to estimate height and biomass of mangrove forests. Trust me, the look on the participants’ faces after they finalized their first biomass maps was exhilarating. The knowledge gained in this training will enable the use of the most up-to-date information on the state of mangroves along the entire coast in Guyana’s national forest.

From my perspective, the best part of the workshop was going out into the field. On the last day, we visited a nearby mangrove restoration site and moving through the forest was no easy task! At the end of the visit, we were lucky to still have our boots on from our struggle to walk in the deep, sticky mud. The participants were instructed to measure tree height, diameter at breast height (DBH) and establish forest plots using clinometers (a fancy word for an instrument that measures elevation, slope, and depression of an object), laser range finders for measuring the distance to an object, and measuring tapes for recording tree diameter. With this information (known to scientists as validation data) we are able to calibrate the equations we use to model mangrove forests with remote sensing.

I am really looking forward to our continued work with this enthusiastic group of people and to be back in Georgetown for a follow up training in May of this year. We are planning to do a “hackathon” as the second phase to develop the mangrove monitoring system.