Boreal spring can look a lot like winter. Over the past three days the Boreal Centre has gotten snow, snow, and more snow. According to Nicole we’ve gotten more snow in the past few weeks than they got all winter! But snowflakes weren’t alone in the sky; we also witnessed a flurry of robin activity. The snow conditions on Sunday and Monday were harsh enough to prevent the robins from traveling, but not cold enough to discourage them from foraging. We spent both days pacing between the windows in the Boreal Centre watching a flock of about 50 robins flitting around the treetops. To encourage the robins to forage near our nets we did our best robin impressions and kicked snow away to reveal open spots of bare ground. Luckily for us, with the snowy conditions halting their migration the flock used the opportunity to fuel up. In just two days we caught 14 robins!

The Boreal Centre in a snowstorm on April 23 (top). Robins perched in the bushes near our net. The net is nearly invisible, but extends to the left from the vertical pole (bottom).

Nicole kicking snow to create suitable spots for robins to forage for food (top). Bringing back two successfully caught robins (bottom).

Despite the rising temperatures and sun breaking through the storm clouds as we rolled up our nets on Monday night, we woke up to the largest snowfall we’ve seen on Tuesday morning. The snow was so deep that we knew no robins would be able to forage on our field if we didn’t help them out. We grabbed our shovels and cleared foraging trenches around each of our nets, hoping hungry robins would take advantage of them. Unfortunately, Tuesday’s weather must have been stormy enough to convince the robins to take a true snow day as we only saw a couple of individuals. We only caught one bird but it turned out to be a relative of the robins, the Hermit Thrush.

Shoveling snow (left) to create foraging tracks around our nets (right).

A sole robin braving the heavy snowfall on April 25th.

A relative of the American Robin, the Hermit Thrush.

We are excited to introduce our Space Robins who braved the snow! Meet Saturn, Falstaff, Mighty Robin, George, Mama Ray Ray, Frightful, Daniela Broccoli, Jerry, Shina, Robert, Red, Twitter, Ariel, and Fluffy.

The robins and hermit thrush weren’t alone in exploring the snowy boreal forest. Plenty of Dark-eyed Juncos were out looking for food and we captured a Rusty Blackbird, Black-capped Chickadee, Fox Sparrow, and Sharp-shinned Hawk. The Rusty Blackbird also breeds in the boreal forest but is one of the most rapidly declining species in North America for reasons that are largely unknown. This particular Rusty Blackbird was the first one ever caught at the Boreal Centre! The Sharp-shinned Hawk follows a similar migration pattern to the robins. Although they are the smallest hawks in North America, they are fierce predators of the robins despite similar sizes. When we released the Sharp-shinned into the forest we learned why. As soon as we let her go, she quickly gained speed while navigating the dense thicket of willows.

Dark-eyed Junco tracks in the snow.

The Rusty Blackbird.

Sharp-shinned Hawk.

Black-capped Chickadee.

Fox Sparrow.

A walk in the snow revealed that I’m not the only one who uses the trails in the park. I found dog-like footprints in the snow and scat nearby, both of which were sure signs of a coyote. Can you guess what this coyote was eating?

Coyote tracks (left) and scat (right). The scat is full of light-colored fur and part of a hoof. This coyote seems to have eaten at least part of a deer!

We currently have 21 Space Robins flying for us—check back as we find our final 9!

We are singing again! Or at least our speaker is, in the hope of enticing robins on to the field. After our success in attracting the attention of migratory robins with a recorded call, we have been trying to draw in more robins by playing it through a wildlife speaker. We noticed that one robin was particularly interested in the speaker. After taking a closer look at him, we saw he was wearing a band. We place a band around the robins’ legs we catch so that they can be identified by us, or other researchers, even after their GPS backpacks have fallen off. Bird bands are tiny aluminum bracelets that weigh next to nothing, but have a unique ID number stamped on them. To learn more about banding birds, click here.

Last year we recaptured a robin wearing a backpack a week after we had originally caught him. We were fairly certain he was breeding here and done migrating since he had stuck around for a week, so we took his backpack off to put on another robin. The robin that was intent on checking out our speaker was wearing a band. He’s very likely the same bird we caught last year. That means our resident robin came to breed at the Boreal Centre again!

The returning, resident robin inspecting our speaker.

It may be that the singing worked, or entirely coincidental, but we saw the largest flock of robins so far. Nicole estimated that there were about 120 robins! As the flock descended onto the grass, our resident robin fiercely defended his territory. How many robins can you count in this video?

Some thing, or some predator, spooked the flock, because they flew off very quickly. Fortunately some of them ended up in our nets.

Carrying five robins in their bird bags into the lab (left). Tying a knot to secure the GPS backpack (right).

We put a dot of glue on the knot to ensure it does not come undone (left). A Space Robin ready to fly (right).

Meet Star, Scuttle, Fury, Mr. Noodle, and WiFi!

Boreal beavers

Last year we noticed lots of evidence of beavers at work around the Boreal Centre. Although we saw signs of the beavers, we never saw any of them in action.

Here’s a movie that shows a beaver pond near the Boreal Centre. Can you guess who has chopped down all of the trees?

The other night, my mom and I ventured over to the beaver complex around sunset and there they were! Two beavers were swimming in the pond they had created!

Beavers are remarkable swimmers, partly because of their webbed hind feet. Did you notice the beaver slapping his tail on the water? He does this to scare predators (and in this case, me). The beaver was entirely comfortable in the water, despite the melting ice, because of his dense coat of fur. Beavers change their environment to suit their needs. Beavers build dams to create ponds, which help them escape from predators in the water. Beaver ponds create habitat for other species, like fish and waterfowl. Because of their critical role in creating habitats, beavers are often referred to as a “keystone species.”

Check back soon for more updates on the Space Robins and their boreal neighbors!

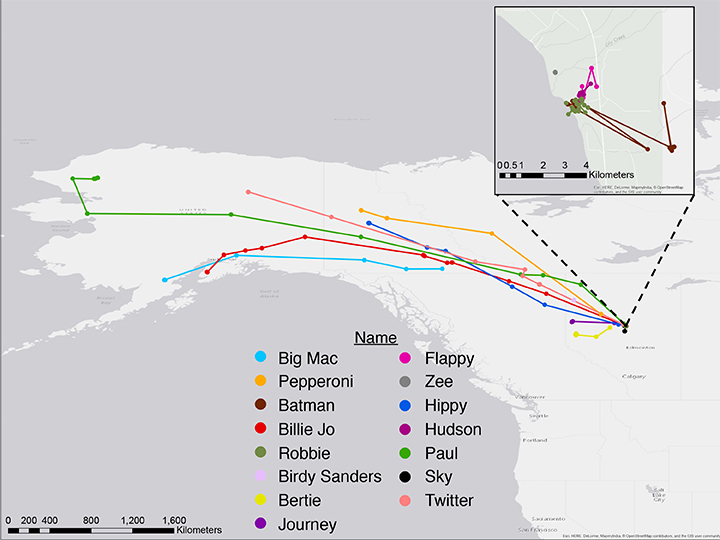

We are back on the search for Space Robins to help us solve our migration mystery! Remember, last year we set out to track American robins migrating through Canada and Alaska to understand where they go and why. Check out our first post from last year to learn more about the project in general. With the help of our friends Nicole and Richard Krikun of the Lesser Slave Lake Bird Observatory and Boreal Centre for Bird Conservation and mini-GPS units from Lotek, we successfully followed fifteen robins to their breeding grounds. Check out the map below to see where our Space Robins went!

This year, our team of researchers has changed a bit. I’m Ruthie, a student at Columbia University and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory working on my Ph.D. in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences. My friends, and birding experts, Nicole and Richard will be helping me again. But this year my mom Kitty, a bird enthusiast, will be tagging along.

Ruthie Oliver and Nicole Krikun in front of a snowy Boreal Centre.

Kitty Oliver, the newest Space Robin team member.

We are curious to discover what types of environmental conditions might cause robins to change their movements as they search for a place to breed and raise their chicks. Because environmental conditions can change quite bit from year to year, especially in the arctic tundra and boreal forest, we are back in Alberta to find 30 more robins to help us untangle their migration mystery. This year we are hoping that if environmental conditions, like snow cover, are different from last year it will help us understand what types of conditions robins prefer when they travel.

You are what you eat…

If you notice on the map of our robins from last year, we know where they ended their journey, but we don’t know where they started. Because of this we don’t know which robin actually traveled the farthest. Another migration mystery! Do you have any guesses on where the robins might be coming from? Do you have any ideas how we might figure out where our robins spent the winter?

Remember the saying “you are what you eat”? It’s true! Foods that are grown in different places are different when you look at them very closely by studying the atoms that they’re made of. Atoms of the same element can weigh different amounts and are called isotopes. The amount of different isotopes found in a plant depends on the type of plant and where it was grown. The isotopes in plants show up in the feathers and toenails of robins. So this year, we will collect feathers and toenail clippings from our robins. By looking at the carbon and hydrogen isotopes of the feathers and toenail clippings, we will be able to learn about where our robins are coming from. Click here to learn more about isotopes.

Spring and snow in the boreal forest

Robins aren’t the only ones who are affected by the environment. When we landed in Edmonton, Alberta on Friday we were all set to drive 3 hours north the Boreal Centre. But a big snowstorm made the trip too difficult, so we had to wait for the weather to improve before completing our migration. As we waited in Edmonton, we could only imagine that the robins were probably hunkered down waiting out the storm too. The next day as we drove, we got a glimpse of what the boreal forest looks like in the winter.

With snow on the ground and cold temperatures, we weren’t optimistic about catching many robins at the Boreal Centre very soon. While we waited we prepared our GPS backpacks. We wanted make sure they fit the robins, but we needed a robin to a measure on. Usually we don’t want to lure robins in with calls because birds that respond are likely to be breeding in the area and are no longer migrating. But since we just wanted to try out suiting up a Space Robin, we didn’t mind if it was living around here. So we downloaded robin calls to play through a speaker and set out a decoy stuffed bird. We got the attention of our local robin we had seen around, but before we knew it we had attracted quite a crowd! About two-dozen robins took to perching in the tree near our speaker to try to figure out who was singing. Because they were in such a big group, it seemed like they were most likely still migrating, but just taking a break in the snow.

Our decoy robin (actually a Red-winged blackbird stuffed animal) singing.

Waiting behind the nets for robins to come.

Robins coming over to check out what all the singing is about.

And that’s how we met our first two Space Robins—Dream and Lightning Guinea Pig!

Here’s how we suit up a Space Robin:

Check back here for updates as we find our next Space Robins!