This story is the answer to the November puzzler.

As autumn inches toward winter, seasonal changes emerge across the Northern Hemisphere. In mid-September 2021, vegetation on northeast Siberia’s Cape Navarin had already turned from green to brown, and snow covered some of the higher elevations. By late October, the entire cape was blanketed in white. Cooler temperatures and shorter sunlit days were also transforming the ocean, as wisps of sea ice started to appear just offshore.

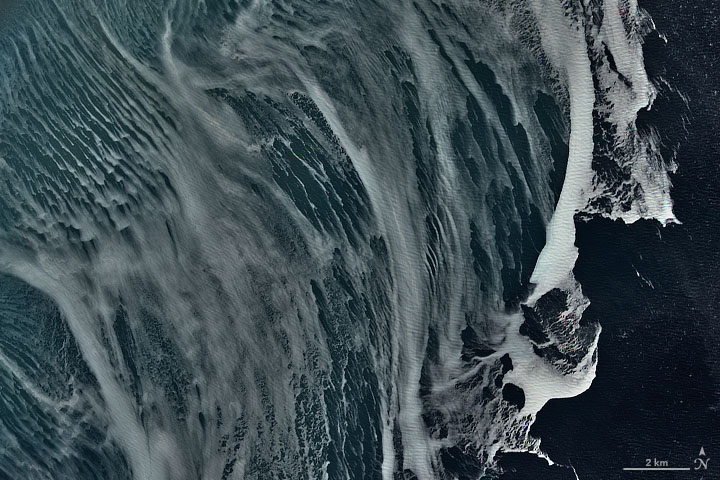

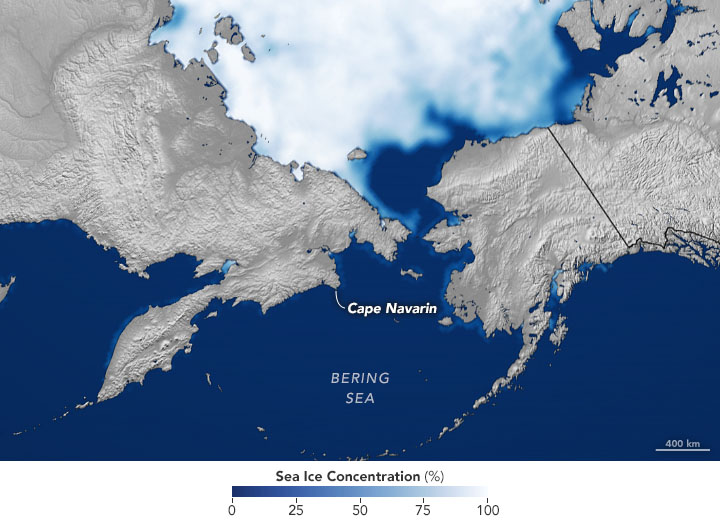

Swirls of ice were visible off Cape Navarin on November 2, 2021, when the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 acquired these natural-color images. The wide view shows the snow-covered cape, which forms the southern boundary of the Gulf of Anadyr—a large bay of the western Bering Sea. The detailed view shows patterns in the sea ice as it traces the coastal current.

According to Kay Ohshima, a scientist at Hokkaido University, the sea ice is showing up right on time. In the western Bering Sea, ice tends to first form along shallow coastal shelf areas of the Gulf of Anadyr, usually by mid-October. But growth of sea ice here is quite variable; it can continue growing until February (in warm years) or as late as the end of April (in cold years). Either way, sea ice in the western Bering is usually completely gone by mid-June.

The Bering Sea spans 2 million square kilometers at the northern edge of the Pacific Ocean, and is connected to the Arctic Ocean through the Bering Strait. Sea ice is an important part of the Bering Sea ecosystem, providing habitat for birds and marine mammals. It even helps support phytoplankton blooms in spring, when freshened water (from melting ice) and nutrients are more abundant near the ocean surface. Also, sea ice in the Bering can help dampen the impacts of storms and flooding on coastal communities.

It remains to be seen how Bering Sea ice will progress through the 2021-2022 winter. In spring 2020 and 2021, sea ice in the Bering has grown close to the average extent for springtime, following a record low extent in 2018 and a near record low in 2019. A recent study showed that 2018 saw the lowest expanse of winter ice in 5,500 years—driven to such a low by human-caused climate change. The paper’s authors suggest the Bering Sea could be free of ice year-round by 2100.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center. Story by Kathryn Hansen.