In western Washington, fog forms frequently in the summer and fall. Skies are often clearer than in other seasons, allowing surface heat to escape and air to cool, which leads to fog. But fog can happen any time of year if conditions are right.

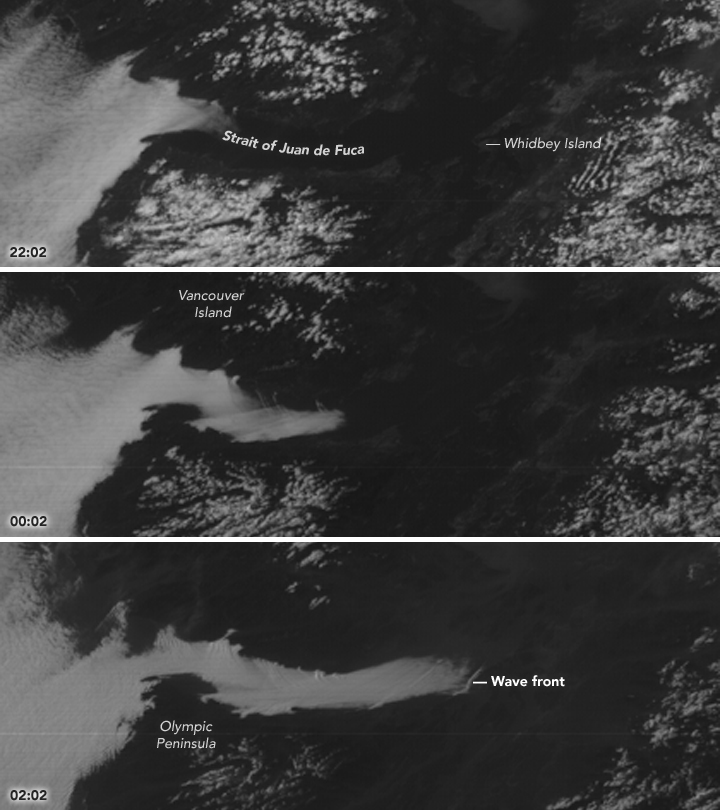

Conditions were right on May 20, 2017, when winds pushed coastal fog eastward from the Pacific Ocean into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the channel between Washington state and Vancouver Island. The images above were acquired by the Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI) on GOES-16. The satellite is operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which includes the National Weather Service. NASA helps develop and launch the GOES series of satellites.

The GOES satellites are particularly well suited to capture the movement of clouds and weather systems because these satellites follow Earth’s orbit and maintain a fixed position over a region. For phenomena that evolve quickly—like storms, or in this case, fog—this so-called geostationary orbit gives a timely view.

GOES captured this series of images on May 20 as fog rolled into the strait. At 3:02 p.m. local time (22:02 Universal Time), stratus clouds hung low off the coasts of Washington and British Columbia. Within two hours, the fog was about halfway into the strait; two hours later, the fog encountered the sharp landmass of Whidbey Island, which imparted a wave structure to the clouds.

The images composing the animation begin at 10:37 a.m. local time (17:37 Universal Time) and were acquired every five minutes. They show the fog snaking its way into the strait over a span of nine hours.

According to Scott Bachmeier, a research meteorologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, winds that afternoon were about 17 miles (28 kilometers) per hour, with gusts that evening up to 31 miles (50 kilometers) per hour. It’s not uncommon for fog to fill the strait; lower-resolution GOES and the Suomi NPP satellite imagers captured similar views in August 2016 and April 2013.

“This fog feature and its motion were more accurately depicted by the improved spatial and temporal resolution of GOES-16 imagery,” Bachmeier said. “The small-scale “bow shock waves” would probably not have been seen with lower-resolution GOES visible imagery.”

The images are based on preliminary, non-operational data from GOES-16. NOAA recently announced that GOES-16 will be moved to replace the GOES-East satellite by the end of 2017. In addition to observing weather on Earth, GOES-16 carries instruments for monitoring solar activity and space weather.

NASA Earth Observatory images and video by Jesse Allen, using GOES 16 imagery provided courtesy of the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies (CIMSS) at the University of Wisconsin. Story by Kathryn Hansen.