When a large section of the Larsen B ice shelf crumbled into a melange of floating icebergs and drifted away in 2002, glaciologists suspected they would see even more changes to the ice in the Antarctic Peninsula during the coming years.

The nearby Larsen A ice shelf collapsed in a similar fashion in 1995, and in the aftermath the tributary glaciers that fed that floating platform of ice continued to thin and stretch for years. Rather than stabilizing after the breakup, many of Larsen A’s tributary glaciers actually accelerated their slide toward the Weddell Sea.

There is now little doubt that similar changes have affected Larsen B’s tributary glaciers. Chris Shuman—a University of Maryland at Baltimore County glaciologist based at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center—and colleagues at the National Snow and Ice Data Center and the University of Toulouse have scrutinized observations from numerous satellites and aircraft instruments over the past decade, and the trend is clear. “Ice loss has continued unabated since the collapse,” Shuman said. “In recent years, the rate of elevation change has slowed a bit for some glaciers, but for others we are seeing more thinning and ice loss.”

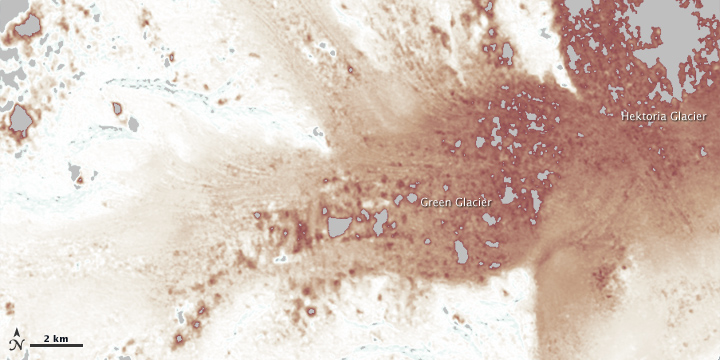

Some of the most dramatic changes in recent years have occurred at Hektoria and Green glaciers, tributaries on the northern edge of Larsen B drainage basin. Between 2002 and 2006, the two glaciers lost an average of 4.2 gigatons of ice per year; between 2006 and 2011, they lost 5.6 gigatons per year. In their lower reaches, the two glaciers have lost about 220 meters (720 feet) of vertical thickness since 2002.

The colorful visualization above is a digital elevation model (DEM) difference map based on satellite images acquired in 2002 (top) and 2012 (middle) by the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) on NASA’s Terra satellite. The elevation model shows the dramatic thinning that has occurred since 2002. Red areas signify changes (drops) in the height of the ice. Gray indicates a lack of data, due primarily to cloud cover. ASTER creates DEMs by capturing several views of the same scene from slightly different angles, providing a stereoscopic view that can be used to reveal changes.

While changes are most evident in the elevation map, signs of the ice shelf loss are also visible by comparing the 2002 and 2012 images. Notice, for instance, how much more of the mountain ridges are visible above the ice in the 2012 image. Also, the lower edge of the Green and Hektoria glaciers—the terminus—is not visible in the 2002 image. It is visible amidst the melange of floating icebergs on the lower right side of the 2012 image. The crevasses covering the ice surfaces in the 2012 image are another sign of rapid thinning and stretching.

The Hektoria and Green glaciers are not the only glaciers in the Larsen B basin that have thinned over the past decade. The Evans, Punchbowl, and Jorum glaciers have also thinned, though not as much. A bit farther to the south, the Crane Glacier underwent 90 meters of thinning in 2004-2005, and its total elevation change—180 meters—rivals that which has occurred at Hektoria and Green in recent years.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using data from NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team. Caption by Adam Voiland.