Editor’s note: This article is the first in a series on how trends in air pollution affect burdens of disease in urban areas. Read part 2 at: No Breathing Easy for City Dwellers: Particulates.

NASA-funded scientists have, for the first time, connected health outcomes in cities around the world to satellite and ground-based data on air pollution. The researchers concluded that despite improvements in some parts of the world and for certain pollutants, air quality continues to be an important contributor to disease. Mitigating pollution is crucial to public health, especially for children, who can be particularly susceptible to respiratory diseases such as asthma.

“Nearly everyone in any city around the world is exposed to air that has harmful levels of air pollution in it,” said lead author Susan C. Anenberg, an associate professor of global health at the George Washington University and a member of NASA's Health and Air Quality Applied Sciences team.

Globally, air pollution is the fourth leading risk factor for death. Some pollutants are concentrated around urban areas, where about half the world’s population lives. In highly developed countries, closer to 80 percent of the population lives in urban areas. “We know that air pollution and population are both co-located in urban areas,” Anenberg said, “but we’ve never before had estimates of the burden of disease from air pollution in cities around the world.”

The studies by Anenberg and colleagues focused on nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and fine particulate matter (PM2.5). Nitrogen dioxide—which is largely produced by emissions from cars, trucks, and buses—is associated with the incidence of pediatric asthma. It is also a precursor to ozone and PM2.5—the leading cause of death related to air pollution.

In the studies, the teams combined two decades of satellite observations made across 13,000 urban areas worldwide with health data from the Global Burden of Disease study, a comprehensive study on health, risk factors, disease, and death in 204 countries around the world. “This is the first time that we have concentrations for all urban areas around the world,” Anenberg said. “And not just what concentrations of pollutants people are exposed to, but what this means for their health.”

The map above shows the change in annual average nitrogen dioxide concentrations between 2000 and 2019. The map is based on data from a land use regression model, combined with data from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument on Aura. The team used these datasets to expand several years of ground-based monitoring data up to a global scale at high resolution.

The researchers then paired the NO2 concentrations with population data and asthma rates from the Global Burden of Disease study. This allowed them to estimate the incidence of pediatric asthma attributable to nitrogen dioxide between 2000 and 2019. They estimated that 1.85 million new asthma cases globally in 2019 were attributable to nitrogen dioxide. Two-thirds of these new cases occurred in urban areas.

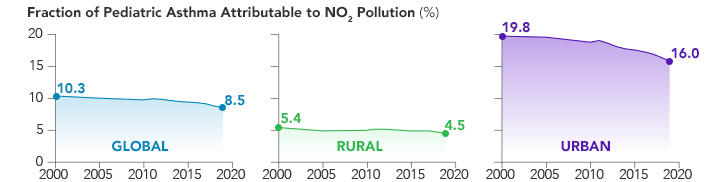

The chart above shows the fraction of all asthma cases globally, as well as in rural and urban areas, that were attributable to nitrogen dioxide pollution. The urban rate declined (from 19.8 percent to 16.0 percent) but the total number of cases in urban areas stayed about the same, with 1.22 million cases in 2000 and 1.24 million cases in 2019.

“The percentage of asthma cases attributable to nitrogen dioxide went down, and that is good news,” Anenberg said, “but it was balanced out by growth in population. That was why we had about the same number in 2000 versus 2019.”

Urban asthma cases attributable to nitrogen dioxide increased in south Asia, sub-Saharan and north Africa, and the Middle East. Many other areas of the world—both high-income and low-income economies—saw declines in NO2 and asthma rates.

However, despite some declines in nitrogen dioxide concentrations in some regions, it is “not enough to ensure that children are breathing clean air,” Anenberg added. “About three-quarters of cities globally have nitrogen dioxide concentrations that exceed the current World Health Organization guidelines.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using data courtesy of Anenberg, S. C., et al. (2022). Story by Sara E. Pratt.