Sea ice in the Northern Hemisphere is not limited to the cap of ice that tops the Arctic Ocean; seas around and south of the Arctic Circle also can get a seasonal covering. These satellite images, acquired in March 2020, show ice in the Sea of Okhotsk—one of the lowest latitudes (down to 44° North) in the Northern Hemisphere where a sizable amount of seasonal sea ice forms each year.

Ice formation here is aided by cold westerly winds that blow out from East Siberia for much of the winter. Freshwater from the Amur and other rivers also helps ice form in parts of the sea. When freshwater mixes with seawater, the water mass becomes fresher (less saline) than seawater alone, which allows it to freeze at a warmer temperature.

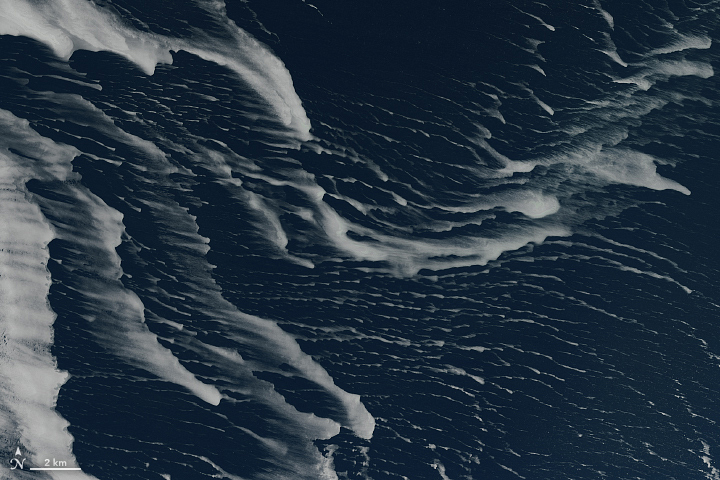

The two images above, acquired by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8, show thin sea ice in the Sea of Okhotsk on March 12, 2020. The area shown is just off the southeastern coast of Sakhalin, Russia’s largest island. Much of this ice likely started forming north of the island and was then carried south by the Sakhalin Current, which flows south along the island’s east coast. Northwest and west winds likely pushed the ice to the southeast and east, as evidenced by the streaks.

Starting between mid-January to early February, sea ice usually moves south toward the waters off Abashiri, a port town on the northeastern coast of Hokkaido, Japan. Residents and tourists celebrate the arrival with the Abashiri Okhotsk Drift Ice Festival. “Drift ice” (Ryuhyo in Japanese) is the name for sea ice that is moved by winds and currents.

Drift ice was still visible around Sakhalin and Hokkaido on the last day of winter, when the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite acquired the third image. It’s not likely to last long, however, as spring will soon bring warmer air and water to the region.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS/LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Kathryn Hansen.