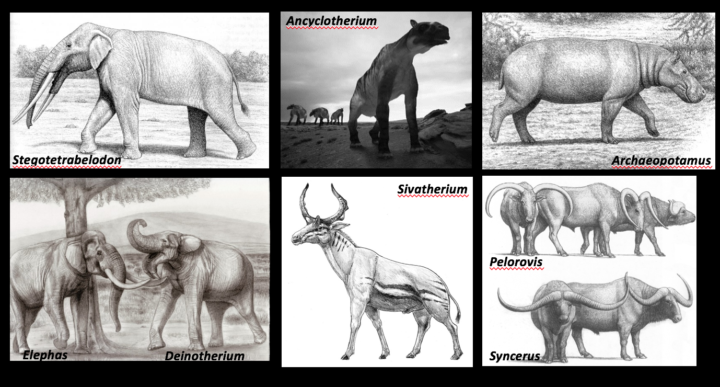

Seven million years ago, some truly spectacular creatures roamed the woodlands of East Africa. There was a moose-like giraffe called Shiva’s beast. There were giant buffalo with horns wider than the animals were tall. And the lumbering creatures known as anthracotheres defy easy categorization.

“Whenever I ask colleagues who study anthracotheres how they describe them, they always say: hippo-pig,” laughed Tyler Faith, curator of archaeology at the Natural History Museum of Utah. As for the buffalo: “This was a horn span of 3 meters (10 feet). I mean this was an awesome buffalo.”

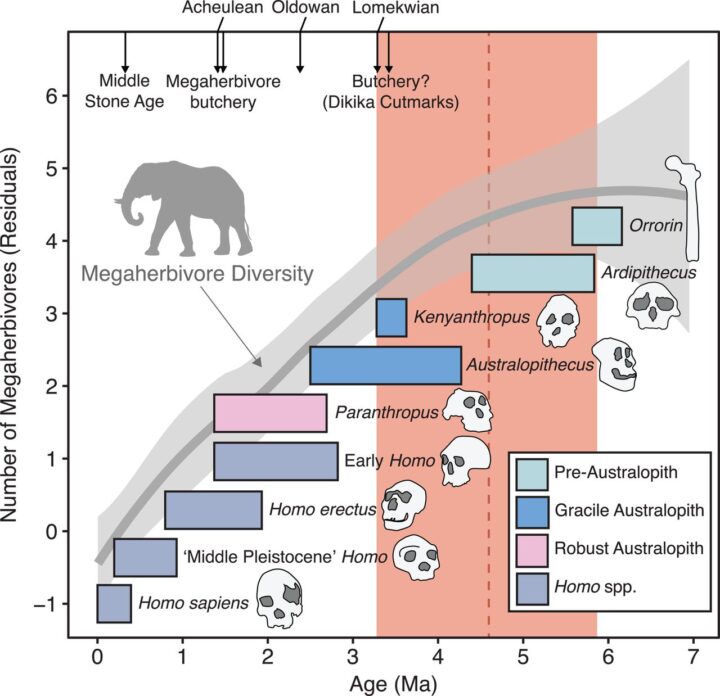

These and several dozen variations of more recognizable African megaherbivores — elephants, rhinos, hippos, and giraffes — all went extinct within the past several million years. For decades, archaeologists have pinned the blame on early humans, particularly Homo erectus, a species that emerged 2 million years ago, walked upright, and had a body plan similar to modern humans. Since Homo erectus made stone weapons and was capable of butchering large game, many archaeologists assumed that it hunted Africa’s megaherbivores into extinction — much like the fossil record suggests Homo sapiens (modern humans) did to the large mammals of North and South America some 11,000 years ago.

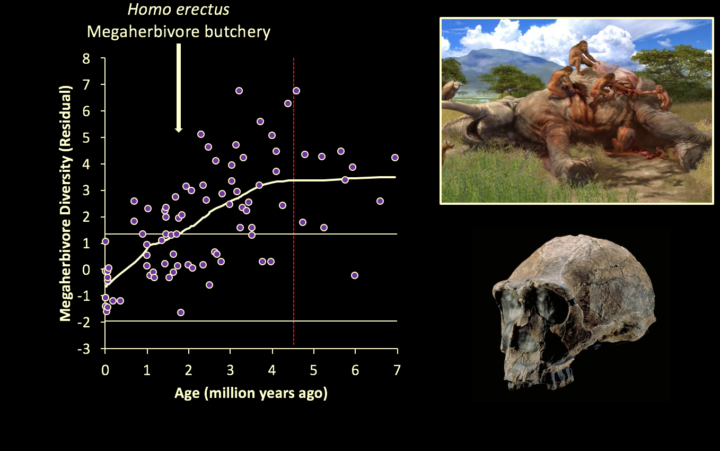

But nobody rigorously tested whether this “overkill hypothesis” fit with the fossil record. “Speculation had been repeated often enough that it just graduated into fact; it became the truth,” Tyler explained during a recent colloquium at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. To check more rigorously, Tyler and colleagues analyzed fossil assemblages from 101 sites in Eastern Africa.

What they found was a surprise. Megaherbivores began disappearing about 4.6 million years ago — long before Homo erectus came on the scene (1.8 million years ago). And there was no increase in the rate of extinctions even when Homo erectus and butchering showed up in fossil records.

However, when the researchers looked at some key indicators of past environmental conditions, they found one key change — the expansion of grasslands — lined up with the extinctions almost perfectly. Five million years ago, classic open grasslands like today’s Serengeti Plain did not exist in East Africa. Trees and shrubs were a much more dominant part of that African landscape then, explained Tyler.

But as carbon dioxide levels declined, mainly due to orbital variations and changes in the amount of Earth covered by ice, forests retreated and grasslands became dominant. Since many of the megaherbivores fed mainly on woody vegetation, they likely faded away along with their food sources. Meanwhile, other familiar species thrived. The ancestors of wildebeest, hartebeests, Thompson gazelles, oryx, plains zebras, and warthogs — all grazers that live in open habitats — proliferated.

Faith’s bottom line is that it is time to stop blaming Homo erectus for something they didn’t do. “In the search for ancient hominid impacts on ancient African ecosystems, we must focus our attention on the one species known to be capable of causing them – us, Homo sapiens, over the past 300,000 years,” he said.

In the early 19th century, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark led an ambitious expedition across the western United States. They greatly expanded our knowledge of the country’s geography and biological diversity through their specimen collection, mapping of the landscape, and detailed journal entries.

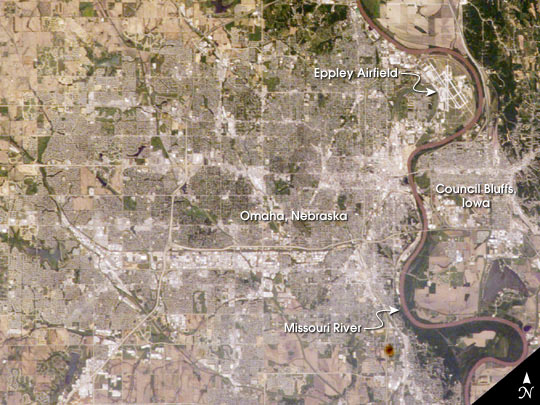

This year NASA and the National Park Service are encouraging the public to follow in the footsteps of Lewis and Clark through a new citizen science challenge. From June 1 to September 2, citizens are invited to use their smart phones and the NASA GLOBE Observer app to map land cover along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail to assist scientists studying environmental changes.

Land cover–such as grass, pavement, or trees–influences the water and energy cycles and influences a community’s vulnerability to natural disasters. NASA studies land cover changes from space as part of its mission to better understand our planet and improve lives.

To participate in the “GO on a Trail” challenge, download the free GLOBE Observer app from the Apple App Store or Google Play. Use the Land Cover tool to make observations of the landscape. Any observation made along the 5,000-mile-long Lewis & Clark trail from Pittsburgh to the mouth of the Columbia River earns points. The top participants will receive recognition and GO on a Trail commemorative material.

A good place to get started is at an observation station marked with a large sticker (image above) at Lewis and Clark visitor centers and museums. To navigate to sites of interest along the trail, the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail and GLOBE Observer teams have provided an online map.

“We hope that by becoming involved with this project, people will care about the trail and become its stewards,” said Dan Wiley, chief of integrated resource stewardship for the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. Wiley notes that the challenge will both spark a general interest in science and show the public how it can be involved in collecting vital information for decision makers.

GLOBE Observer is an app-based citizen science program active in more than 120 countries. The program invites citizens to contribute land cover, cloud, mosquito, and tree height observations to NASA and the science community. NASA-funded scientists are eager to see citizen science observations of land cover along this trail because of its wide range of ecological regions. Data collected during the challenge could help improve satellite-based mapping of land cover across the continent.

“We are observing and monitoring our changing home planet from space to better understand how it is changing and what are the main drivers of change,” said Eric Brown de Colstoun, a scientist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. “The view from the ground provided by the challenge participants is one component that helps us verify the space-based data.”

Even if you are not able to visit the Lewis and Clark Trail this summer, you can still join the GO on a Trail challenge from any of the more than 120 countries where GLOBE Observer is active. Just get outdoors and map the land cover around you. The top participants from beyond the trail will also receive recognition and commemorative material.

“Lewis and Clark and their team were exploring a totally new environment to them,” said Brown de Colstoun. “We invite you to get out and explore, and document the places you know and care about. Go on a trail and do science along with us.”

NASA GLOBE Observer and Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail will provide regular updates about the GO on a Trail challenge via social media throughout the summer with the hashtag #GOonaTrail. Follow GLOBE Observer on Facebook @nasa.globeobserver or Twitter @NASAGO. Follow the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail on Facebook @lewisandclarknht, Twitter @lewisclarktrail, and Instagram @lewisandclarknht or visit the website at: https://www.nps.gov/lecl/index.htm.

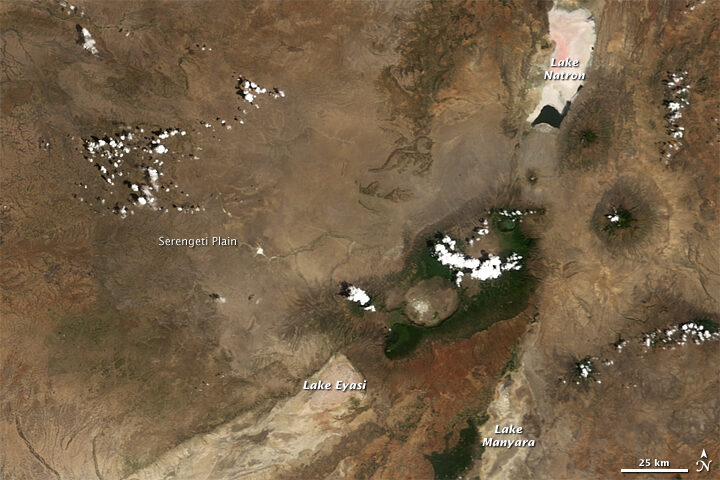

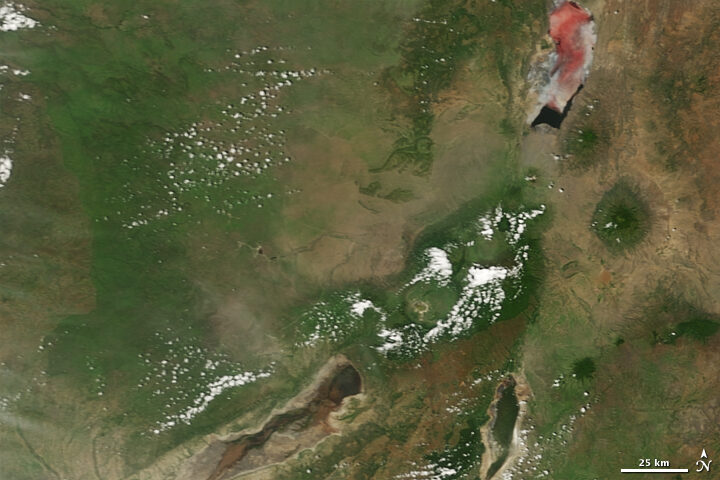

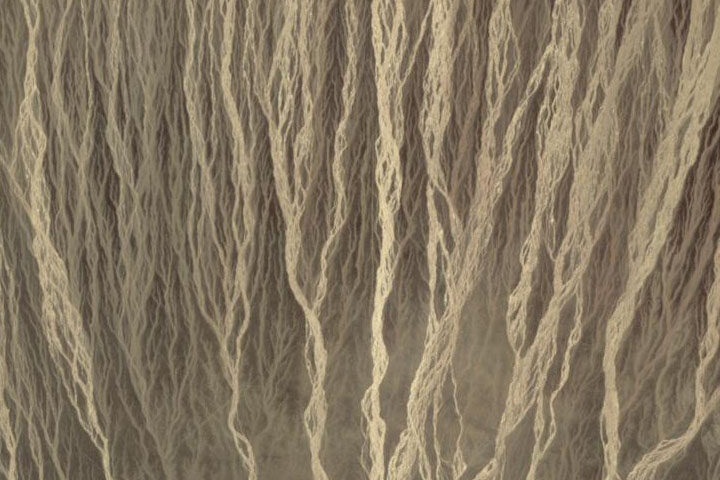

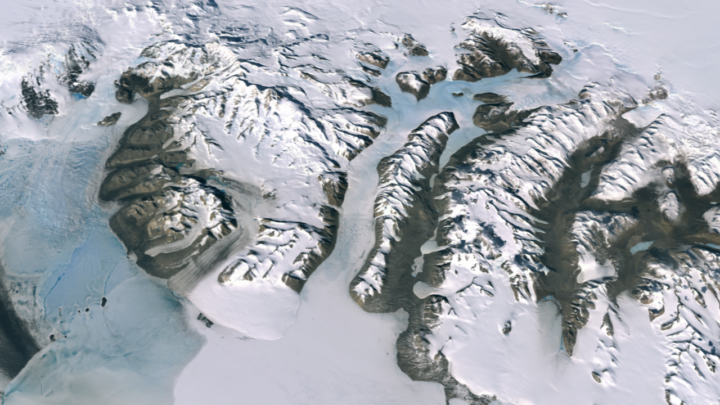

Every month on Earth Matters, we offer a puzzling satellite image. The May 2019 puzzler is above. Your challenge is to use the comments section to tell us what we are looking at and why it is interesting.

How to answer. You can use a few words or several paragraphs. You might simply tell us the location. Or you can dig deeper and explain what satellite and instrument produced the image, what spectral bands were used to create it, or what is compelling about some obscure feature in the image. If you think something is interesting or noteworthy, tell us about it.

The prize. We can’t offer prize money or a trip to Mars, but we can promise you credit and glory. Well, maybe just credit. Roughly one week after a puzzler image appears on this blog, we will post an annotated and captioned version as our Image of the Day. After we post the answer, we will acknowledge the first person to correctly identify the image at the bottom of this blog post. We also may recognize readers who offer the most interesting tidbits of information about the geological, meteorological, or human processes that have shaped the landscape. Please include your preferred name or alias with your comment. If you work for or attend an institution that you would like to recognize, please mention that as well.

Recent winners. If you’ve won the puzzler in the past few months or if you work in geospatial imaging, please hold your answer for at least a day to give less experienced readers a chance to play.

Releasing Comments. Savvy readers have solved some puzzlers after a few minutes. To give more people a chance to play, we may wait between 24 to 48 hours before posting comments.

Good luck!

Update: The answer to the May Puzzler is available here. Congratulations to Dan Mahr for being one of the first readers to recognize that this was part of an alluvial fan.

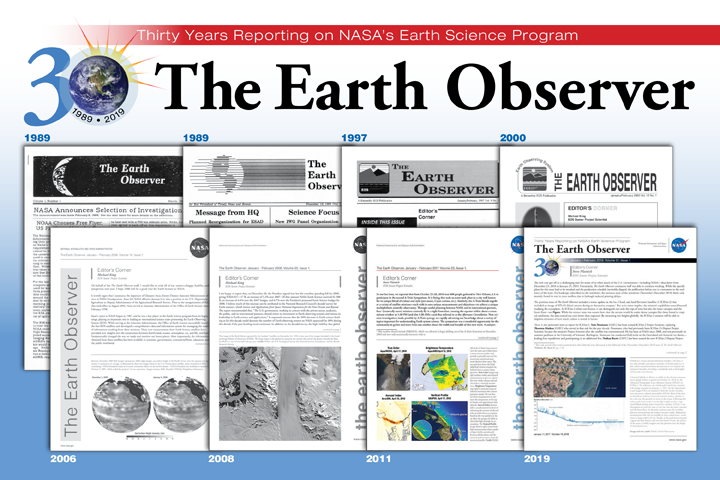

The March–April 2019 issue marks the thirtieth anniversary of the release of the first issue of The Earth Observer newsletter in March 1989. Alan Ward has spent much of his career working on this publication—including 13 years as Executive Editor—and has written a reflection to mark this milestone. The following version has been edited for length. You can read the full story here.

Spurred on by the successes of pioneers in satellite remote sensing, in the early-to-mid-1980s a concept emerged to obtain coordinated Earth observations from space. The earliest designs envisioned having several large platforms in orbit, each carrying many instruments, that could be serviced via the Space Shuttle, akin to how the Hubble Telescope was reserviced. However, that approach eventually morphed into the present fleet of small-to-mid-sized satellites launched on unmanned rockets: e.g., Terra, launched on an Atlas IIAS rocket; Aqua and Aura, both launched on Delta II rockets. The idea was given a name: the Earth Observing System (EOS).

Making EOS a reality would require a fundamental shift in how scientists studying Earth approached their research. Traditionally, individual science disciplines tended to focus on their own areas of expertise, and only occasionally worked together. The idea behind EOS was to study the Earth as a system of interrelated systems—an approach that came to be known as Earth System Science. Functionally, that meant that scientists from different disciplines would need to collaborate much more frequently than they had in the past.

In short, EOS was a grand vision: that we’d someday have a fleet of satellites (along with complementary ground observations and computing systems) continuously taking the pulse of our home planet and sending back large amounts of data—and that scientists would come together to work on related topics. But just how would it all work in practice? No one knew for sure back then. Ask anyone who attended early EOS meetings what they were like and they are likely to use words such as “chaotic” and “challenging” to describe them. In an article he wrote for The Earth Observer, Darrel Williams [former Project Scientist for Landsat 7, currently Chief Scientist at Global Science & Technology, Inc.] recalled that Pier Sellers once described the overall experience of trying to take EOS from idea to reality as being, “…like putting socks on an octopus.”

Sellers definitely had a unique way with words. Whatever creative metaphor one might use to describe it, there is no doubt that those first EOS investigators had huge challenges before them! Not only did they have to work out the details of the flight hardware and computing systems for EOS almost from scratch, but they also had to figure out the practical details of how they would actually work together.

As challenging as developing space flight hardware was (and still is), at that time there was an even larger logistics issue that needed to be addressed. A huge program involving hundreds of researchers strewn all over the nation—and eventually the globe—was trying to get off the ground, and the participants needed the means to communicate. The Internet, which we take for granted today, was in its infancy at that time. If you wanted to get the word out about upcoming meetings, results from those meetings, announcements, and the like, print media was still the way to go. Enter The Earth Observer!

Space does not permit the full story of the intimately interconnected history of the evolution of The Earth Observer and EOS to be repeated here. For this context, it suffices to say that the idea, or concept of EOS faced a difficult journey—and evolved a great deal—before it became what it is today, and that, from its inception, The Earth Observer has chronicled that story.

By the time I made my first contribution to The Earth Observer in 2001, the EOS Earth observing satellite fleet was beginning to take shape. Terra had been launched only a couple years earlier and the other flagship missions (Aqua and Aura) would follow in the next three years. During my tenure, I’ve watched the EOS Program come of age. The Earth Observer has chronicled the establishment and now graceful aging of members of NASA’s Earth-observing fleet of satellites, and has also reported on airborne and ground-based sensors.

We continue to report on NASA Earth Science as we move beyond the EOS era into the Suomi NPP and JPSS era, and into other endeavors such as Decadal Survey missions, including the Earth Venture element. We’ve reported on the launches of new (or recently launched) missions along the way, as well as on the remarkable scientific achievements of existing platforms as, one by one, they exceeded their planned mission lifetimes—often by many years—and celebrated a decade or more in orbit.

I noted earlier that EOS wasn’t simply a satellite-based program. The Earth Observer has also reported on the complementary ground elements, describing results from field campaigns and other ground-based observation programs over the years.The Earth Observer has also published feature articles on more-general topics, such as Earth Science Mission Operations, responsible for keeping the fleet flying safely, and Earth Science Data Operations, which includes the EOS Data and Information System, better known as EOSDIS.

Perhaps the series I take the most personal pride in is our Perspectives on EOS series, which ran from 2008 through 2011. It really didn’t begin with a series in mind; it started with an article that I wrote for the newsletter’s twentieth year, and grew organically into a compendium of recollections and memories from key members of the EOS program. It is often said that history is the telling of a personal story, and that was certainly true with these articles, as the storytellers had actually lived them.

In many ways, the current publication doesn’t look much like the first issue did in March 1989, shortly after the official beginning of EOS. However, while much has changed aesthetically and in terms of content in 30 years, The Earth Observer’s core commitment remains the same as it has always been: to report timely news and events from NASA’s Earth Science Program.

It has been my honor to serve as executive editor for a baker’s dozen of years, and I look forward to seeing what comes next for The Earth Observer as we begin our fourth decade. I think it’s been a good run so far—but I hope our best is yet to come!

On April 29, 1999, NASA Earth Observatory (EO) started delivering science stories and imagery to the public through the Internet. So much has changed in those 20 years…

+ In 1999, about 3 to 5 percent of the world had Internet access. About 41 percent of American adults used the World Wide Web, most often to look at the weather. Today an estimated 56 percent of the world’s population (4.3 billion people) are active on the Internet.

+ At the end of the 20th century, all EO readers came to us through a computer, mostly desktops. One third of them were connecting via dial-up modem. Today, about 40 percent of our audience arrives to the web site via mobile phones and tablets on public wifi and cellular networks. Yet even now, 65,000 of our most loyal followers subscribe to our newsletters. Many others subscribe to our RSS feeds.

+ In 1999, “social” media mostly consisted of chatrooms and newsgroups. Even by 2005, only 5 percent of Americans were using social media. Today about 69 percent of adults use social media, and people are just as likely to see Earth Observatory content on social platforms as on our web site. Ten million people follow EO and NASA Earth science on Facebook, with 1.3 million more on Twitter, and 500,000 on Instagram.

+ When EO launched, images from Earth science satellites were generally available about a month after acquisition. Public access to science data and imagery was extremely limited, highly filtered, and sometimes required a fee. Two decades later, many NASA Earth science observations are available freely on the web within hours of acquisition.

+ On our first day online, the site got 400 pageviews–most of them were likely colleagues and relatives. Today we get about 50,000 views per day.

+ In our first year, we published 35 “Images of the Week” and 9 feature stories. By 2001, we started delivering an Image of the Day. Since launch, we have published more than 6,900 Images of the Day, 8,300 natural hazards images, and 450 features and videos. Yes, more than 15,000 image-driven stories, and all of them are still available in our archive.

+ In 1999, two members of our staff were in elementary school and three were in high school. The readers of EO Kids were not born yet.

The technology of science and the Internet has changed in a generation, and our site has evolved and grown with the changes. But our core values have not changed. You find us on more platforms and with some new approaches, but you can still count on us to deliver beautiful, newsworthy, interesting, and scientifically important images and stories. Our editorial team has more than 110 years of experience in science communication and data visualization, and we bring that depth of knowledge to every story, 365 days a year.

None of this would be possible without the many scientists, engineers, communicators, data hounds, patrons, and friends inside and outside of NASA who review our work, tip us off to stories and images, share their scientific insights, and inspire and challenge us. Thank you.

As we celebrate our 20th year, we are going to share some looks back and some looks ahead. In the next twelve months, look for…

If you have been with us for many (or all) of our 20 years, thank you. We have some of the most engaged, challenging, and thoughtful readers on the planet, and we work hard to live up to your trust and interest. If you are new to the site, bring a friend. We have 15,000 stories about Earth to share, with more being added every day.

Related Links and References

Earth Observatory 10th Anniversary

Pew Research Center (2018) World Wide Web Timeline

Internet World Stats (2019) Internet Growth Statistics

Wikipedia (2019) Global Internet Usage

The shiny metallic orb hanging in the Earth sciences building at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center looks a lot like a fixture you might find at a modern home décor store. But this mid-century marvel is not for sale. It is a restored flight backup of Vanguard II, Earth’s first weather satellite.

The satellite model was hung this week as a reminder of the people who helped build the foundation for making space-based observations of Earth. Paul Newman, chief scientist for Earth science at NASA Goddard, described the satellite:

“Vanguard II was the world’s first meteorological satellite. Developed at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), it was successfully launched by newly formed NASA on February 17, 1959. Vanguard carried two photocells that could scan cloud cover as the satellite rotated in its orbit around the Earth. Unfortunately, the 3rd stage SLV-4 launch vehicle burn caused a precession in the satellite that made the data unusable.”

“While the now silent Vanguard II continues to orbit the Earth, its back-up brother has been restored and mounted in the Goddard Space Flight Center’s Earth Sciences building’s atrium—a fitting resting place amongst the scientists and meteorologists who monitor and study our Earth.”

Some of those scientists, and five retirees from the original NRL Vanguard II team, gathered on April 15, 2019, at NASA Goddard to celebrate the satellite’s 60th anniversary. Angelina Callahan, historian at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, reflected on the historical importance of the Vanguard era. From building satellites and their launching vehicles, to putting satellites in orbit and tracking them, the achievements of the program helped pave the way for satellite missions that followed.

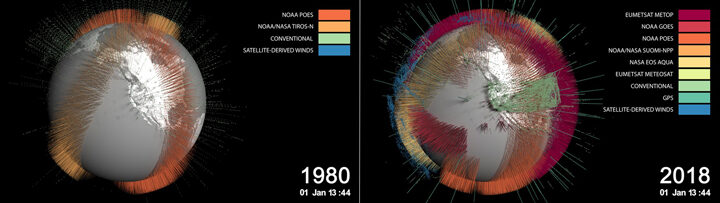

The reflection was also a study on how much has changed. Ron Gelaro, an atmospheric scientist at NASA Goddard, discussed weather prediction in the modern satellite era. Vanguard II carried two photocells and weighed just 21 pounds. The Aqua satellite—launched in 2002 to collect information on Earth’s water systems—carries six instruments and weighs more than 6,000 pounds. Gelero noted, however, that satellites are starting to trend back toward smaller vehicles, such as constellations of microsatellites.

The amount of observations available for understanding weather and climate have also skyrocketed over the decades. For example, MERRA-2 is a reanalysis project at NASA Goddard that combines satellite measurements of temperature, moisture, and winds in the GEOS model. In 1980, MERRA assimilated 175,000 observations for every six-hour period. That number in 2018 neared 5 million observations.

According to NRL: “The scientific experiments flown on the Vanguard satellites increased scientific knowledge of space and opened the way for more sophisticated experiments. Vanguard was the prototype for much of what became the U.S. space program.”

In fact, about 200 scientists and engineers from the Vanguard program moved from NRL to the newly formed NASA in 1958—forming the core of NASA Goddard. You can read more about Vanguard here.

For Earth Day 2019, NASA invites you to celebrate the planet we call home with our #PictureEarth social media event.

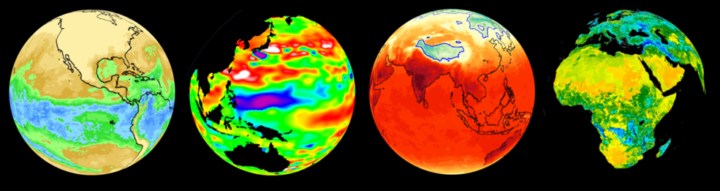

NASA studies Earth as part of its mission. Our satellites and instruments #PictureEarth daily. Some take visible light photos, much like your camera. Others peer into the infrared, microwave, ultraviolet, or radio spectrums, which human eyes cannot see. Each satellite image or data set reveals a small detail of the land, water, atmosphere, and life on Earth.

How do you #PictureEarth?

Show NASA how you see your planet by posting photos on social media. Focus on the details around you with close-up images.

What makes your location special?

What are the textures, colors, or patterns in your surroundings?

Look for Earth’s dynamism, motion, and beauty: blooming flowers, crashing waves, sturdy trees, furry and feathered animals, molten lava, puffy clouds, smooth ice, and warm sunlight.

Share your best Earth photo!

On Earth Day — April 22, 2019 — share your best photos of Earth on social media with the hashtag #PictureEarth. Be sure to tell us where your photo was taken. We love to read posts from around the world because NASA Earth data is available to everyone – we all live on this planet together.

We’ll be watching on Instagram, Twitter, and our Facebook event page for your images and messages. As with our previous Earth Day events, we’ll select some of the publicly-shared photos to showcase in videos and composite images featuring your beautiful imagery.

Then download the NASA Earth photo book

To see how we #PictureEarth from space, download the new Earth photo book or read it online: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/earth-book-2019

On April 15, 1999, Landsat 7 first made its way into space. 106,380 orbits later, the 2.6 million images acquired by Landsat 7 have given us a fuller and more nuanced understanding of Earth.

Take for example the Millennium Coral Reef Mapping Project. In 2006, Landsat 7 data were used to create a first-of-its kind global survey of coral reefs. The research lead on this project, Frank Muller-Karger, commented in 2015: “Until we made the map of coral reefs with Landsat 7, global maps of reefs had not improved a lot since the amazing maps that Darwin drafted.”

Landsat 7 data, together with data from its predecessor Landsat 5, provided the most comprehensive assessment ever of Earth’s mangroves in 2010.

And for the International Polar Year (2007-2008), data from more than 1,000 Landsat 7 images were used to create the Landsat Image Mosaic of Antarctica (LIMA)—what was then the most detailed satellite mosaic of Antarctica.

If we travel two decades back in time and rewind the 4,733,375,587.686 kilometers that Landsat 7 has flown since April 1999, we arrive at a very different moment in spaced-based Earth observation.

The commercially-owned Landsat 6 satellite had failed to reach orbit six years earlier. Landsat 5 was 12 years past its design life and operated by a for-profit entity that charged upwards of $4000 per image and collected international data only when there was an immediate customer. Both situations curtailed the systematic global coverage of Earth that had been envisioned by the Landsat Program’s founders.

A building consensus about the critical role of Earth observation data for global change research had led the National Space Council to recommend that Landsat 7 be built. It should be operated by the U.S. government to ensure a continuous global archive of medium-resolution data for the long-term monitoring of Earth’s land surface. This was codified with the 1992 U.S. Land Remote Sensing Policy Act.

When Landsat 7 launched on April 15, 1999, the Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) instrument onboard was the most sophisticated Landsat sensor yet. ETM+ carried a new 15-meter panchromatic band and had a thermal band with a spatial resolution refined to 60 meters (compared to 120 meters for Landsat 4 and 5). It also carried a new solid-state data recorder—one of the first to fly on a civilian mission. For the first time in Landsat program history, Landsat 7 was equipped with hardware that could reliably store large amounts of imaged data onboard for later download when a ground station was in range.

Landsat 7’s state-of-the-art recorder, together with a strategic global image acquisition plan, enabled the best global coverage the program had ever known. The LIMA project lead, Robert Bindschadler, penned in a 2001 journal article that “The revolutionary concept of systematic collection of Landsat 7 data timed to optimize anticipated scientific applications will make possible a global monitoring of the cryosphere with a data set heretofore only available in limited regions.”

During its ascent into orbit in 1999, Landsat 7 collected data as it flew under Landsat 5. This enabled the cross-calibration of Landsats 5 and 7. (In 2013, Landsat 8 underflew Landsat 7 for the same reason). Additionally, a team of calibration scientists oversaw in-the-field calibration efforts, making certain that satellite measurements agree with physical ground measurements. Such careful data calibration ensures that the Landsat data record can show meaningful trends of land use and land cover change—even when the changes are subtle.

In May 2003, an image scanning mechanism on Landsat 7 (the Scan Line Corrector) failed, leaving wedge-shaped gaps in the imagery—a net loss of 22 percent of each image. As devastating as this failure was, the remaining data are, as USGS describes, “some of the most geometrically and radiometrically accurate of all civilian satellite data in the world.”

The landmark 2008 USGS decision to make all Landsat data free and open, and the subsequent trend towards best-pixel composite-based data analysis, has made these data gaps even less problematic.

All in all, Landsat 7 has made remarkable contributions to global studies for two decades now, and according to fuel-based predictions, it should be able to continue doing so until the launch of Landsat 9.

In the second it took you to read this line, Landsat 7 traveled about 7.499 kilometers.

The launch of Landsat 7 was the second image ever posted on NASA Earth Observatory.

The Landsat 7 Mission Operations Control Center is staffed by 14 engineers, seven days a week, 8 hours a day. Someone is always on call and ready to respond if a ground or spacecraft anomaly occurs.

References:

Goward, S.N. et al. (2017) Landsat’s Enduring Legacy: Pioneering Global Land Observations from Space. Bethesda, MD: American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing.

Wulder, M.A. et al. (2019) “Current status of Landsat program, science, and applications.” Remote Sensing of Environment 225:127-147.

When we published a few Landsat images of wildflower super blooms in California in March 2019, you may have had to squint a little to find the flowers. From 705 kilometers (438 miles) above Earth’s surface, at the 15-meter-per-pixel resolution of the Operational Land Imager on Landsat 8, the flowers tend to blend with the hues of the desert.

Not so with this colorful photograph of poppies and other wildflowers in Antelope Valley that was taken from a T-34 airplane. The picture was shot by NASA Armstrong aerial photographer Jim Ross, who may have one of the coolest jobs at NASA. Watch the video below to find out how he got it.

Meanwhile, remote sensing scientist Iban Ameztoy was inspired enough by the aerial photos to pull Sentinel-2 satellite imagery of the same bloom and share them on Twitter.

Want more satellite imagery and aerial photography of the super bloom in California? NASA Earth Observatory and NASA Armstrong have you covered.

Join a mosquito mapping blitz for Citizen Science Day through GLOBE Observer.

Earth observations take place on many spatial scales. Some observations originate from sensors in space; others can happen with a mobile phone in the palm of your hand. GLOBE Observer is a free mobile app that connects an international network of citizen scientists with the broader scientific community in an effort to document and analyze changes taking place in Earth’s air, land, water, and life. The app is the centerpiece of a citizen science blitz now underway.

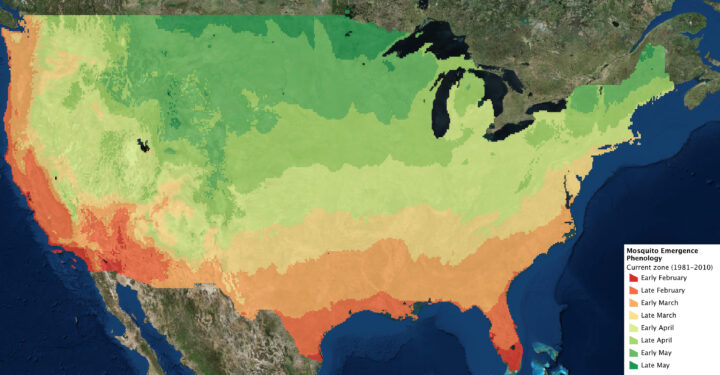

Both globalization and a changing climate have caused countless living creatures to adjust their range and distribution. For human health, one of the most concerning impacts of a changing climate is the range expansion of mosquitoes. These flying vectors of disease are responsible for illness in millions of people; they also cause more than 700,000 deaths each year.

The northern hemisphere is now greening up in response to changes in sunlight and temperatures, and mosquito season is either just beginning or underway in much of the contiguous United States. The map above indicates when the first appearance of mosquitoes can be expected based on past weather data. The actual time of first appearance in a region can vary by several weeks, depending on the weather and other variables.

The GLOBE Observer app has a new tool known as the Mosquito Habitat Mapper, which makes it possible for citizen scientists to observe, record, and share data about mosquito breeding sites using a mobile phone. The data are important to scientists trying to predict disease outbreaks and epidemics. Observations provided by citizen scientists, combined with satellite observations and models, can make it possible to track the range and spread of invasive mosquitoes.

With the Mosquito Habitat Mapper, citizen scientists can report active and potential breeding sites in their communities. And using a built-in taxonomic key, GLOBE Observers can help determine whether the mosquito larvae have the potential to transmit disease pathogens to humans.

GLOBE Observers also can have an immediate impact on health in their community. In the last step of Mosquito Habitat Mapper, users report whether they were able to remove a breeding site. This can be accomplished in most cases by simply tipping and tossing standing water that is found in containers, or by covering stored water with a net or a lid. For larger water bodies such as ponds, irrigation ditches, or swamps, the reports about breeding sites can be used by mosquito surveillance agencies.

In this way, GLOBE Observers are not only engaged scientifically, they can become agents of change in their community. The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies source reduction–the elimination of mosquito breeding sites–as the most effective way to protect human populations and reduce the threat of mosquito vector-borne disease.

The GLOBE Observer Mosquito Blitz kicked off on April 7, 2019, and ends on Citizen Science Day (April 13). Join in this effort by downloading the app. Follow GLOBE Observer on social media during Mosquito Blitz week on Facebook or Twitter. Check out the Mosquito Blitz website and GLOBE Mission Mosquito for more mosquito resources.