In summer 2016, flooding of historic proportions swamped China.

The trouble began in June, when seasonal monsoon rains became torrential and fell day after day after day. Daily rainfall records were broken in several cities, and many areas recorded more than 200 millimeters (8 inches) of rain in just 24 hours. Macheng (Hubei province) received 285 millimeters (11 inches) of rain in one day.

By July 5, flooding and associated mudslides had affected 11 provinces, destroyed 40,000 homes, ruined more than 1.5 million hectares of crops, and killed 128 people. And that was just the beginning.

Another burst of heavy rain arrived from the southeast when cyclone Nepartak made landfall in Fuijan province in mid-July. The storm destroyed tens of thousands of homes and forced hundreds of thousands of people to evacuate. Meanwhile, weather systems arriving from the west continued to march across the Yangtze River Basin extending and exacerbating the flooding. By the end of July, provinces in northeastern China had been hit with widespread and destructive flooding, as well.

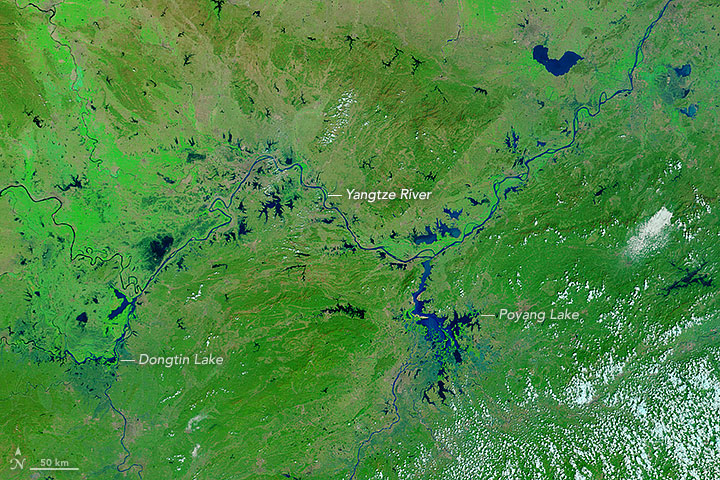

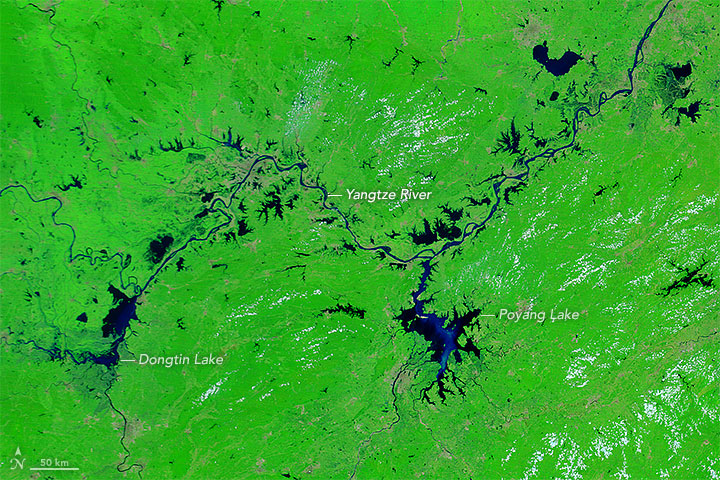

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite captured these images of the Yangtze River Basin on March 27, 2016, and July 28, 2016. The second image marks one of the first satellite passes in several weeks that allowed us to see the flooded landscape. Both images use a combination of infrared and visible light to increase the contrast between water and land. Vegetated land appears in varying shades of green; water appears in varying shades of blue; and urbanized areas range from gray to red-brown. Clouds are light blue. The difference in the greenness of the surrounding landscape is due to seasonal growth of vegetation.

Notably, Poyang Lake, Donting Lake, and other wetlands along the Yangtze River were unusually low in March. If water levels had been closer to normal in the spring, the damages from the summer flooding likely would have been far more severe. However, the damages from China’s 2016 floods have already topped more than $22 billion (U.S.), according to the International Disasters Database. That makes the floods the second most expensive natural disaster in China, and the fifth most expensive disaster on record outside of the United States, noted Weather Underground meteorologists Jeff Masters and Bob Henson.

The deluge was not unexpected. Heavy rain often affects China after an strong El Niño year. Indeed, after a strong El Niño in 1998, similar floods struck the Yangtze River Basin, causing $44 billion in damage and 3,656 deaths. Multiple studies also suggest that global warming is likely increasing the intensity of the monsoon in Asia.

NASA image by Jeff Schmaltz, LANCE/EOSDIS Rapid Response. Caption by Adam Voiland.