If you go up one step from the Grand Canyon on the geological “Grand Staircase” of the western United States, you will reach Zion National Park. Zion is the middle step on this tilted, eroded, staircase-like feature of the Colorado Plateau. It connects the very old, exposed sedimentary rocks of the Grand Canyon with the relatively newer rocks of Bryce Canyon.

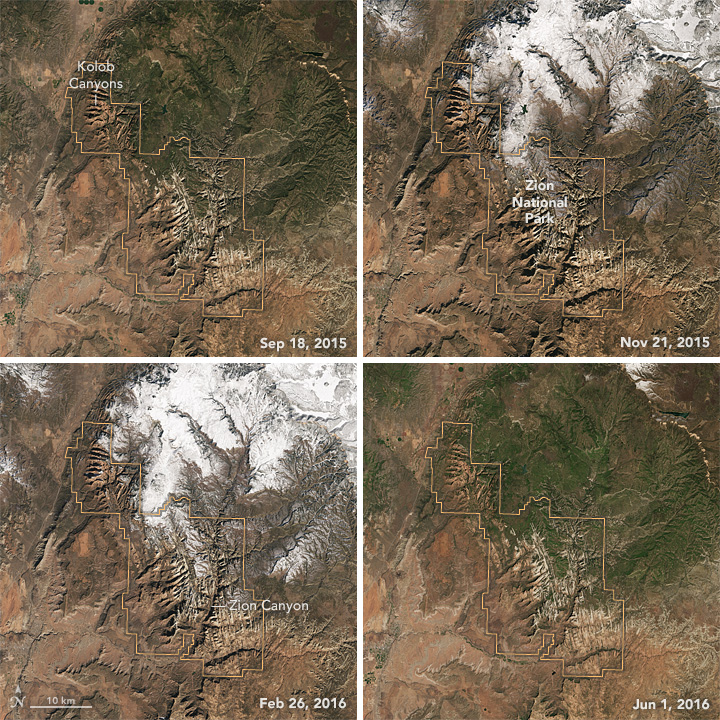

The images above, acquired by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8, show Zion National Park, which spans 593 square kilometers (229 square miles) of semi-arid desert in southwestern Utah. The four images show the four seasons, starting with fall 2015 (top left) and progressing clockwise.

Most rainfall and snowmelt runs off of the hard, dry surfaces; only a small percent percolates through the sandstone to collect as groundwater. Runoff long ago helped jumpstart erosion in the area, but it wasn’t until about 4.5 million years ago that the Virgin River began sculpting Zion Canyon—one of the park’s most visited features.

The Virgin River is typically calm, not too deep, and hikers in the canyon can easily wade through it. But when the river floods, it has an increased capacity to move huge amounts of sediment downstream. The sediment acts like sandpaper, scouring and deepening the canyon.

In one particularly narrow part of the canyon, aptly named “The Narrows,” the river has cut down through 305 meters (1,000 feet) of rock. In some sections, hikers maneuver though canyon walls only 5 meters (16 feet) wide. Hikers need to be extra cautious, particularly during the monsoon season, as the canyons can quickly flood.

But Zion is not the only canyon in the park worth checking out. The Kolob Canyons area in the park’s northwestern corner takes visitors deep into the desert wilderness. Here you will find Kolob Arch, the world’s longest natural arch, which spans 94.5 meters (310 feet).

NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Caption by Kathryn Hansen.