Snow and ice play an important role in keeping our planet cool, though not in the way you might think.

Snow and ice are bright. They reflect light and energy from the Sun, sending most of it back into space instead of letting it warm the ground. When snow and ice disappear, the darker-colored ocean and land soak up energy instead of reflecting it.

Snow and ice don’t have the same cooling power all year round. During winter, snow and ice dominate the Arctic landscape, but there is no sunlight to reflect. This means that the Arctic doesn’t do much to keep global temperatures cool during the winter. In summer, the Arctic is bathed in light constantly, but there isn’t as much snow and ice to reflect the light back into space.

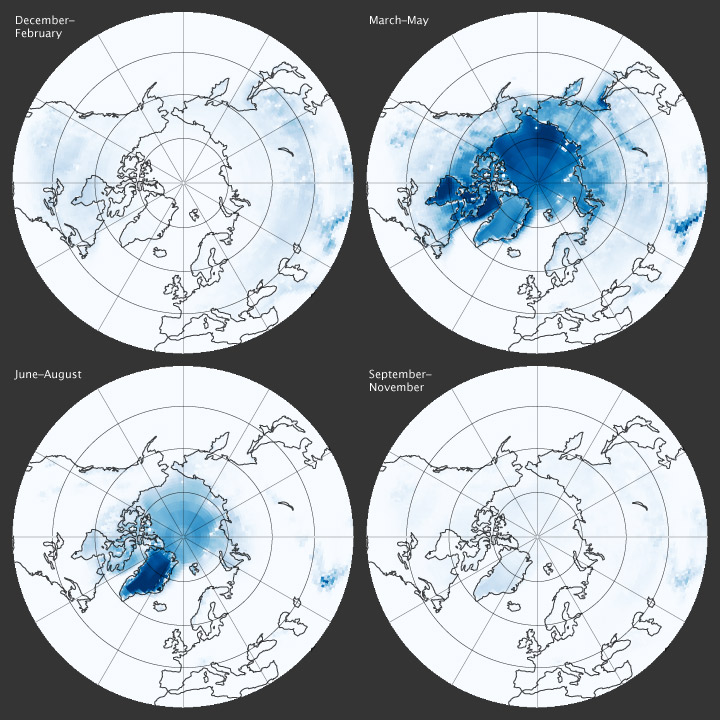

This series of images depicts the amount of energy that snow and ice reflect in each season of the year. The maps were made by combining satellite measurements of snow and ice extent with calculations of the amount of sunlight reaching the ground during the season. Dark blue areas reflect the most energy, having the greatest cooling effect.

As the maps illustrate, snow and ice in the spring (specifically April to June) have a greater impact on global temperatures than snow and ice at any other time of year. This means that changes in spring snow and ice matter more than changes at other times of the year.

In the past 30 years, fall snow cover has increased in the Northern Hemisphere, but spring snow cover has decreased. The change means that snow and ice are reflecting less energy to space overall. The Northern Hemisphere absorbs about 100 PetaWatts more energy now than in 1979—seven-fold greater than all human energy use, says Mark Flanner, the scientist from the University of Michigan who made the maps.

What does all of this extra energy mean for Earth’s climate? A new assessment report from the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program, says that 2005 to 2010 was the warmest period ever recorded in the Arctic, and that these warm temperatures have melted a lot of snow and ice. In particular, snow is melting earlier in the spring. There is evidence that global warming is accelerating as a result of these changes, says the report.

Image by Robert Simmon, made with data provided by Mark Flanner, University of Michigan. Caption by Holli Riebeek.