Over thousands of years, the remains of plants (and animals) that never fully decomposed have become part of the frozen soil in Alaska, Canada, northern Europe, and Russia. Scientists estimate that these frozen landscapes store twice as much carbon as is found in the atmosphere. Ground-based research and models suggest that release of this carbon as permafrost thaws is going to accelerate global warming in the coming century, but increased photosynthesis by tundra plants will help to lessen the impact for a time.

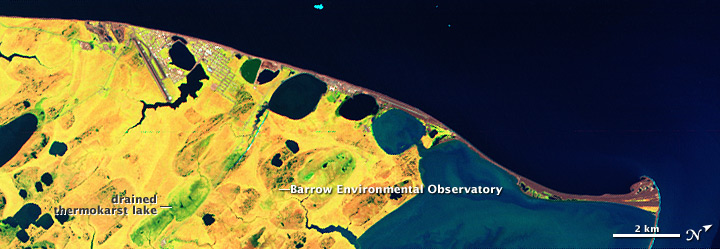

Different plants photosynthesize and store carbon at different rates. To figure out how plant productivity is changing as permafrost thaws, NASA-funded scientists are using hyperspectral satellite images to map the extent of different plant communities in the northernmost part of the United States. This pair of images from the Hyperion sensor on NASA’s EO-1 satellite shows the lake-dotted tundra around Barrow, Alaska, in false color (top) and photo-like natural color. The site is part of the Barrow Environmental Observatory, a large tract of Iñupiat tribal land dedicated to scientific research into Arctic climate and ecosystem change.

False-color imagery uses light in wavelengths that people can’t even see to distinguish landscape features that the eye couldn’t tell apart in photo-like imagery. A natural-color digital image is made from a combination of red, green, and blue light. The Hyperion image above uses shortwave-infrared light in place of red, near-infrared in place of green, and red light in place of blue. Water is dark blue, and undeveloped land areas range from bright green to dull orange to yellow.

According to Fred Huemmrich, from the University of Maryland-Baltimore County, these colors reflect unique habitats and plant communities that are largely influenced by the amount of available water. The leafiest, most productive vegetation in the area appears bright green; located in the soggy depressions of drained lake beds, these plant communities would likely contain more thirsty, grass-like plants called sedges than other areas would. The orange areas are slightly drier and would be favored by mosses and some sedges. The yellow areas are the driest habitats, and would contain plants like heath along with lichens.

The lakes in this area are known as thermokarst lakes. They form when summer melt water ponds up on the permanently frozen ground below. As permafrost thaws, the lakes sometimes drain out through cracks that develop. The warmer soil and the availability of water make these former lake beds oases for plants in the harsh Arctic climate, and Huemmrich has found that these are usually the most productive locations on the tundra. Maps of tundra plant communities should improve scientists’ estimates of carbon uptake and release in the area as climate warms.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Robert Simmon. Caption by Rebecca Lindsey, based on interpretation by Fred Huemmrich, Joint Center for Earth Systems Technology (JCET) at University of Maryland Baltimore County.