The summer minimum and the winter maximum are the two pivotal milestones in the annual cycle of Arctic sea ice. The thickness of sea ice and the extent at each of these times are key indicators of Arctic climate. Over the past two and a half decades, the extent of sea ice at the end of summer (mid-September) has declined significantly. The corollary to that trend is that at the winter maximum (end of February or mid-March), the ice covering the Arctic is much younger and thinner than it was in the past.

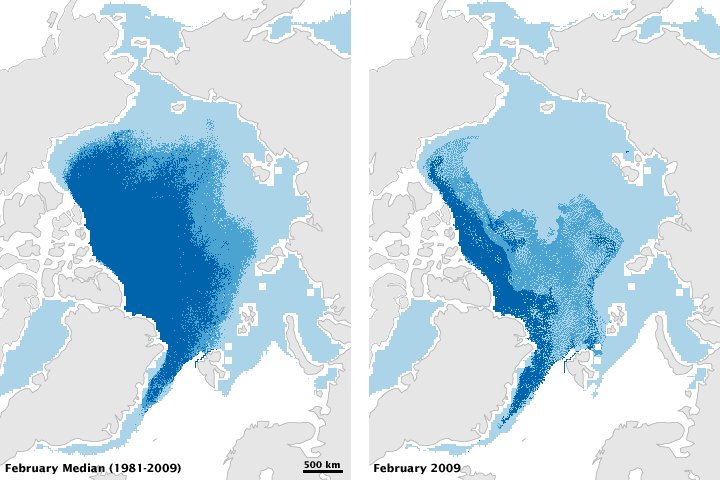

This pair of maps shows the median age of February sea ice from 1981-2009 (left) compared to February 2009 (right). Ice more than two years old is dark blue, ice that is one to two years old is medium blue, and ice that is less than one year old is light blue. Compared to the median conditions at the end of winter (the median is the number halfway between the lowest and highest numbers in a range), the ice pack of February 2009 contains much less old ice (dark blue).

According to calculations from the National Snow and Ice Data Center, ice older than two years now accounts for less than 10 percent of the ice cover. Research from 2007 concluded that, in the central Arctic Basin in 1987, 57 percent of the ice pack was 5 or more years old, and 25 percent of that had been around at least 9 years. By 2007, only 7 percent of the ice was 5 or more years old, and very old ice (at least 9 years) had completely disappeared.

The age of ice in the winter pack is important because young ice is thin and likely to melt in the upcoming summer. Historically, a large “core” of sea ice survived the summer. Around the margins of the perennial ice, new ice forms each winter and melts each summer. Ice that survives the summer melt thickens and hardens through freezing of new water and collisions with other ice floes, which builds thick ridges of ice.

A movie of weekly data from 1982 through 2007 (6.9 MB) shows how small the core of perennial ice has become and how much of today’s pack consists of ice that forms in the winter and melts in the summer. Loss of summer ice reduces the amount of sunlight the Earth reflects to space, amplifying global warming.

In both images, most of the oldest ice is in the western part of the Arctic Ocean basin. This arrangement is the result of the prevailing wind and ocean currents, which cause ice that forms in the Russian Arctic to drift toward the Canadian Arctic. Because of these weather patterns, scientists expect that area to be the “last bastion” of perennial sea ice.

To estimate ice age, scientists track the formation, drifting, and disappearance of sea ice by combining satellite observations with ocean measurements from drifting buoys. Satellite observations come from the Scanning Multichannel Microwave Radiometer and the Special Sensor Microwave/Imager on the U.S. Defense Meteorological Space Program satellites and the series of Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer sensors on National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration satellites. Ocean data come from the International Arctic Buoy Program.

NASA images by Jesse Allen, based on data provided by James Maslanik and Chuck Fowler, University of Colorado and NSIDC. Caption by Rebecca Lindsey, with input provided by Walt Meier, NSIDC.