Ice coverage on the Great Lakes typically reaches its annual peak in late February or early March. But at that time in 2024, the lakes were conspicuously free of ice. Owing to warmer winter weather and above-average surface water temperatures, ice cover stood at historic lows.

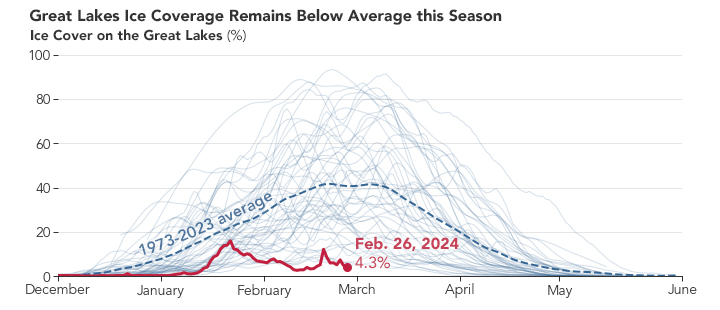

Since satellite-based measurements began in 1973, ice coverage at its maximum winter extent exceeds, on average, 40 percent. In late February 2024, it stood at only about one-tenth of the average maximum. The VIIRS (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) sensor aboard the Suomi NPP satellite acquired this image of the lakes on February 24, 2024.

The extent to which the lakes freeze is highly variable. In 2014, for example, coverage surpassed 80 percent. Since 1973, however, levels have been trending down. Annual maximum ice coverage has decreased by approximately 5 percent per decade, according to NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL). Warmer winter conditions in the Great Lakes region are contributing to more frequent low-ice years.

The chart above shows ice coverage for the 2023–2024 winter season (red) relative to the past 50 winters. The warm start to the current ice season is reflected in this line. Ordinarily, the first cold air masses of the season move over the upper Midwest in December and begin to cool the lake water. This “priming” did not happen in December of 2023, leading to the lowest January ice cover on record in 2024. When an arctic chill lingered over much of the U.S. in mid-January, ice cover grew to its likely season maximum of about 16 percent before dissipating when warmer temperatures returned.

Air temperatures are strongly correlated with ice cover, said Jia Wang, an ice climatologist at GLERL, and four patterns of climate variability influence temperature over the Great Lakes. This year, three of the four patterns exerted a strong influence, said Wang. “El Niño, the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation simultaneously imposed warming to the Great Lakes.”

An absence of ice can make shorelines and infrastructure more susceptible to damage from strong wind and waves. It can also leave some fish species without protection from predators during spawning season. In addition, a lack of ice cover may influence water levels by allowing more evaporation to occur. However, NOAA reported no significant impact on water level as of late February; lake and air temperatures are similar, keeping evaporation rates low.

The Great Lakes ice season runs through March, and it is still possible for blasts of arctic air to reach the region and spur periods of ice formation, according to NOAA experts. However, those cold air events are more likely to be short-lived, and a major shift in weather patterns would be required for this season’s ice to break from its below-average trend, they said.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Michala Garrison and Lauren Dauphin, using VIIRS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE, GIBS/Worldview, and the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership, and lake ice data from NOAA - Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory. Story by Lindsey Doermann.