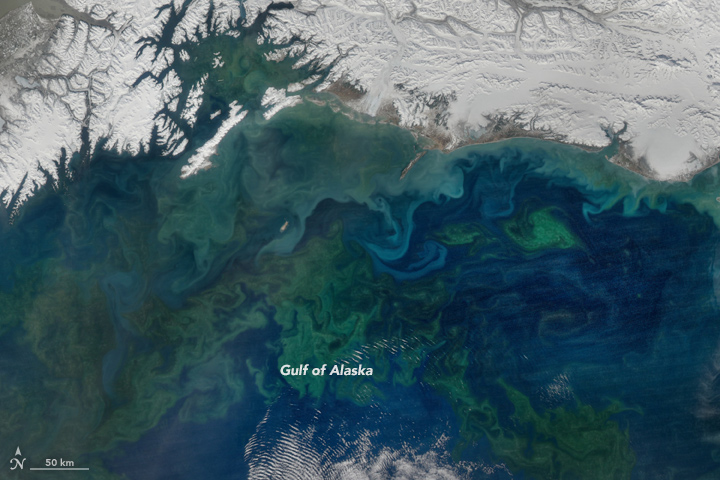

Explosive growth of phytoplankton populations can produce vibrant blue, green, or red displays, covering thousands of square kilometers of the ocean. While phytoplankton play a crucial role in life on Earth, they can sometimes threaten coastal ecosystems, fisheries, and human health through releasing toxins and causing local oxygen depletion. Recent research found that blooms have expanded and become more frequent in the 21st century.

An international team of scientists analyzed 18 years of images from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite to develop a first-of-its-kind global database of coastal phytoplankton blooms from 2003 to 2020. The database documents when and where the blooms occurred.

After analyzing 760,000 MODIS images, the research team found that phytoplankton blooms—which occurred along coastlines of 126 countries—have become 60 percent more frequent during the study period and increased in size by 13 percent. Coastal blooms affected 31.5 million square kilometers, which is 9 percent of all ocean area.

The map above shows trends in the frequency of coastal phytoplankton blooms over the study period. Red areas are where blooms started to show up more often. This trend was observed across most of the Southern Hemisphere and in the high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, according to Lian Feng, who led the research and is a professor at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, China.

The team found that the gradient in sea surface temperatures, used as a proxy for ocean mixing, was correlated with bloom frequency. Phytoplankton thrive on nutrients brought up from the mixing of cooler water deep in the ocean with warmer water above—a process known as upwelling.

Some of the largest increases in bloom frequency occurred in the vicinity of high latitude currents, such as the Oyashio current in the Sea of Japan and the current in the Gulf of Alaska. But some currents, such as California’s current in the Pacific Ocean, reduced upwelling, which led to fewer blooms. Fertilizer use and the expansion of coastal aquaculture production, which add nutrients to coastal areas, were also correlated with coastal blooms in some countries although this relationship was not clear in all coastal areas.

Phytoplankton are fundamental to ocean biology and climate, so any change in their productivity could have a significant influence on biodiversity, fisheries, and the pace of climate change. This research is the first to provide a comprehensive global map of trends in coastal phytoplankton blooms, which was made possible by remote sensing.

The research team noted, however, that the method does not differentiate between phytoplankton species that are harmless and those that produce toxins or are harmful to marine environments. But the future launch of NASA’s Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem (PACE) mission—which will make measurements of the world’s ocean over a broader spectrum of wavelengths—will allow researchers to tease apart which species of phytoplankton are present.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using data from Dai, Yanhui, et al. (2023). Gulf of Alaska image by Norman Kuring, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Emily Cassidy.