The San Joaquin Valley sits like a bowl at the base of the southern Sierra. Close to the middle of that bowl is the historic lakebed of Tulare Lake, which was once the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River. Since the 1920s, the rivers that fed the lake have been dammed and diverted for agriculture and other uses. The lakebed has since been covered with farms that produce a variety of crops and livestock.

But after two major storms hit southern California in March 2023, water once again returned to Tulare. The image above (right), acquired by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8, shows flooded farm fields in the lakebed on April 30, 2023. The image on the left—acquired by the OLI-2 on Landsat 9—shows the same area on February 1, before significant flooding started. These images are false color, which makes the water (dark blue) stand out from its surroundings. Vegetation is green and bare ground is brown.

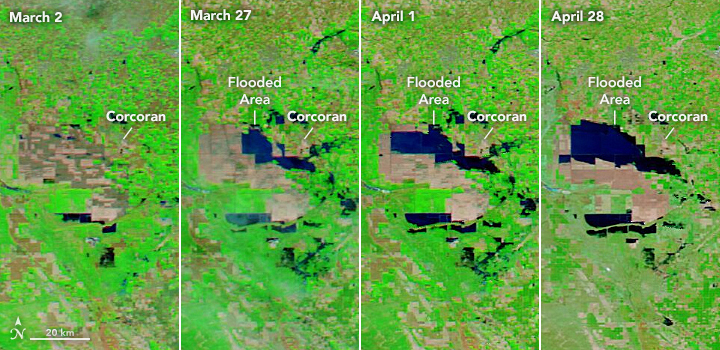

The images below show the progression of flooding in the Tulare Lake basin. They were acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite between March 2 and April 28, 2023.

Flooding in the lakebed is likely to continue into 2024, which will affect residents and farmers in the area, as well as some of the most productive cropland in the Central Valley. The lakebed contains farms that produced cotton, tomatoes, dairy, safflower, pistachios, wheat, and almonds.

The town of Corcoran, on the edge of Tulare’s historic extent, is at risk of flooding from the rising waters. A 14.5-mile L-shaped levee stands between the farm town and the flooding. The community recently began a project to raise the height of the levee by 4 feet, to prevent the levee from being overtopped.

Meltwater from the snowpack on the southern Sierra—which was four times the average in April—is a major source of water for the Tulare Lake basin. Sierra meltwater streams into Kern River, which flows from the Sequoia National Forest in the southern Sierra, past Bakersfield, and ultimately empties into Tulare Lake. Along the way, the river also contributes to Lake Isabella, a dammed reservoir in Sequoia National Forest that has been filling with water this year.

High levels of water along the Kern have led managers to discharge water from the river into ponds just west of Bakersfield. Flooding these recharge ponds allows water to seep into aquifers for long-term storage. The graphic below shows these flooded ponds on April 30, 2023, compared to February 1. The images were acquired by the OLI on Landsat 8 and the OLI-2 on Landsat 9, respectively.

“All the dark blue water you see is being managed in recharge ponds,” said Kern River watermaster Mark Mulkay, after seeing the images. In anticipation of more meltwater coming down from the Sierras, local and federal water managers are releasing water into ponds like these not only to store water for future use but also to prevent uncontrolled flooding along the river and the Isabella Reservoir to the east. “This early water recharge will keep flood water from the Kern out of Tulare Lake to help minimize the flood damages in that area,” Mulkay added.

Snowpack in the Sierras is not finished delivering challenges to the San Joaquin Valley. Spring snowmelt has just begun, and according to the May 1 snow survey by the California Department of Water Resources, snowpack on the entire range is still twice the normal level.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Emily Cassidy.